A little over a month ago, Justified received an email invitation from the NUS Centre For The Arts (CFA) to watch a theatre production, presented as part of the annual NUS Arts Festival series of concerts. I mean, it’s not every day we get exclusively invited to events – I felt almost like an influencer there. #BTCbabes

This production, titled past//present, featured works by two playwrights, Damon Chua and Wang Liansheng. Damon Chua is a playwright, poet, fiction writer and producer based in New York, while Liansheng is a Singaporean playwright and lawyer. These names may be unfamiliar to you, but there is a connection to NUS law; Liansheng is an NUS Law graduate (which earned us the media pass).

In our excitement, we wrote back to express our interest in supporting an alumnus in their pursuits outside of the law. (It wasn’t because of the free tickets at all.) In our curiosity to find out more about life after law school, we asked if we could conduct follow-up interviews.

Admittedly, we ought to have done some research on the history of each of the playwright. But since we didn’t… we contacted them on the basis that both of them were NUS Law graduates and there were some interesting email exchanges that raised more questions than answers.

Here’s an email from Damon –

“Hi [Justified], great to e-meet.

This is my mistake […] I’m not an alum of NUS Law, unless you count the three months I spent there before leaving for overseas.

Sorry for the confusion, guys.”

Eventually, we resolved the misunderstanding; while both Damon and Liansheng studied law in University, only Liansheng is an NUS law alumnus. Fortuitously, Liansheng agreed to be interviewed by Justified. His correspondence with us and subsequent interview will be included in Part 2 of this article series – so stay tuned!

NUS Arts Festival 2018: If We Dream

This theatre production is part of a series of performances, concerts, and visual arts showcases for the NUS Arts Festival 2018. This year also marks the 25th anniversary of the NUS Centre for the Arts.

This year’s Arts Festival is a symbolic reflection of the development of the arts on campus, with the theme “If We Dream”. This theme references the humble beginnings of arts groups in NUS.

The formation of NUS’ first arts group, the University’s Military Band, coincides with the completion of Singapore’s first English language novel If We Dream Too Long by Goh Poh Seng in 1968.

And so If We Dream is a reflection of how this series of performances will envision the same potency, and (sometimes) the perils, of dreaming. In line with this, both writers decided to interpret this theme by exploring the male protagonist’s struggle with societal norms.

The show featured a series of five short works written by Damon and Liansheng. While Liansheng wrote some of his older plays in 2013, Damon’s older works date as far back as 1995, before he left for New York. After getting in touch with each other to work together for this production, both writers eventually decided to would feature some older works from their repertoire, and also write a short response piece to the other’s older pieces.

Showtime

Finally! It was the day of the performance and I made myself comfortable in the cosy black box located in the swanky, newly-renovated University Cultural Centre.

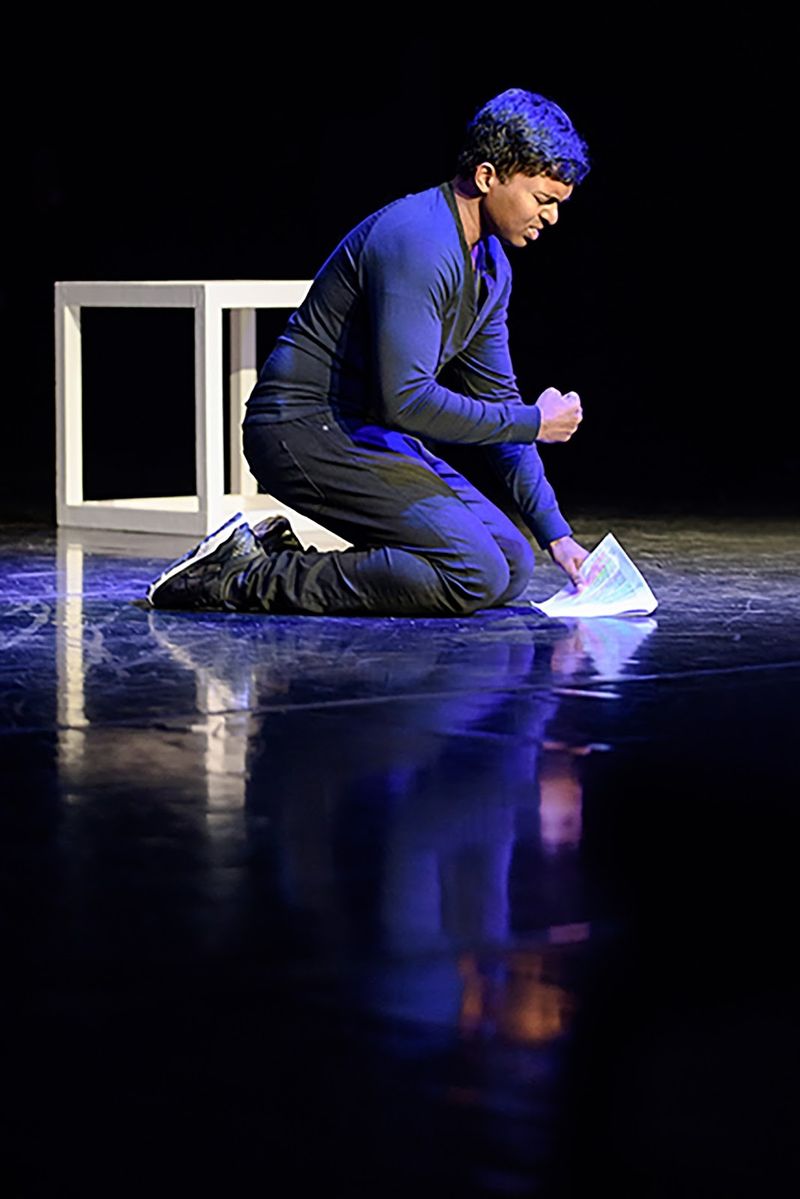

It didn’t take long to see that this production was different from typical theatre shows: the staging was very minimalist, with only a few chairs and white cuboid racks as props. The performers sat along a row of chairs lined along the stage left and right — when they performed, they held their scripts, and when they were done, they returned to their seats. To me, it seemed like an interesting fusion of a dramatic reading and a theatre performance.

This was a novel, yet unexpectedly refreshing experience. The actors used their scripts effectively by retaining enough engagement with the audience. Stripped of elaborate sets and costumes, the focus was on the raw acting. To the credit of the actors, they gave credible and soulful performances which resonated with the audience.

With the legal background of the playwrights (think: surviving finals, equity & trusts, never-ending reading lists and mooting), it is unsurprising that some of their works reflected elements of their academic endeavours, This, I think, would be particularly relatable to most of our readers. One example of such a work was Private Dancer, written by Damon Chua.

Private Dancer by Damon Chua (1995)

Private Dancer is a story of an average Singaporean student told through the perspective of a boy who leaves his family in Malaysia to study in Singapore. The work opens with him reminiscing about playing with his childhood friends at the hilly areas of his Malaysian hometown.

For him, leaving home for school at the end of each holiday is bittersweet. He works hard, eventually getting into law school, much to the delight of his parents. He returns to Singapore and rents a student flat in Clementi with a few other peers, looking forward to university life.

At the start, things are smooth sailing. The actor brings us through freshmen orientation, preparing for a performance with his orientation group. As he sings “We are the Champions” at their finale night, it reminds him of how he felt like the king of the hills in his hometown.

However, life worsens. The study of law is challenging, and he has difficulty adjusting. In a monologue, he describes his struggles: with legalese, the complexity of concepts, and the never-ending work, all while chugging coffee. Despite his effort, his tutor finds his work shoddy. The tutor accuses him of being “playful”, and at one point even questions, “you come to law school for what”?

Through all this, the boy’s stress can be seen in his movements, which become agitated. The stress comes in many forms; for instance, when he calls his parents to complain about his homesickness, they respond by telling him to remain focused on school. His monologue becomes increasingly interrupted by chanting of law terms and sections of the Penal Code. We witness him spiral into stress-induced madness; among his incoherent thoughts, he imagines someone playing the piano, and dances to it. Finally, he looks out of the balcony of his Clementi flat, admiring the view, before realising that slowly, he is falling closer to what he sees. Fin.

Though the inspiration for the play came nearly two decades ago, most of the protagonist’s struggles remain relatable today. Given the competitiveness of law school admissions, most students have to do reasonably well to obtain a place in law school. By extension, they are expected to be able to quickly adapt to the rigour of law school. However, one’s academic performance coming into university does not guarantee one will do well in university. This comes into conflict with the narrative that law students are high-ability individuals who are expected to adapt quickly to the rigour of school.

No one comes into law school knowing exactly what to expect – the protagonist’s struggle between his feelings and the standards imposed on him is a poignant reminder that we all too often forget: it is okay if you are struggling.

If ever you are struggling, do seek the help of your friends, or the team of experienced advisors and counsellors at NUS Law, or even the team at the University Health Center Counselling and Psychological Services (CPS).

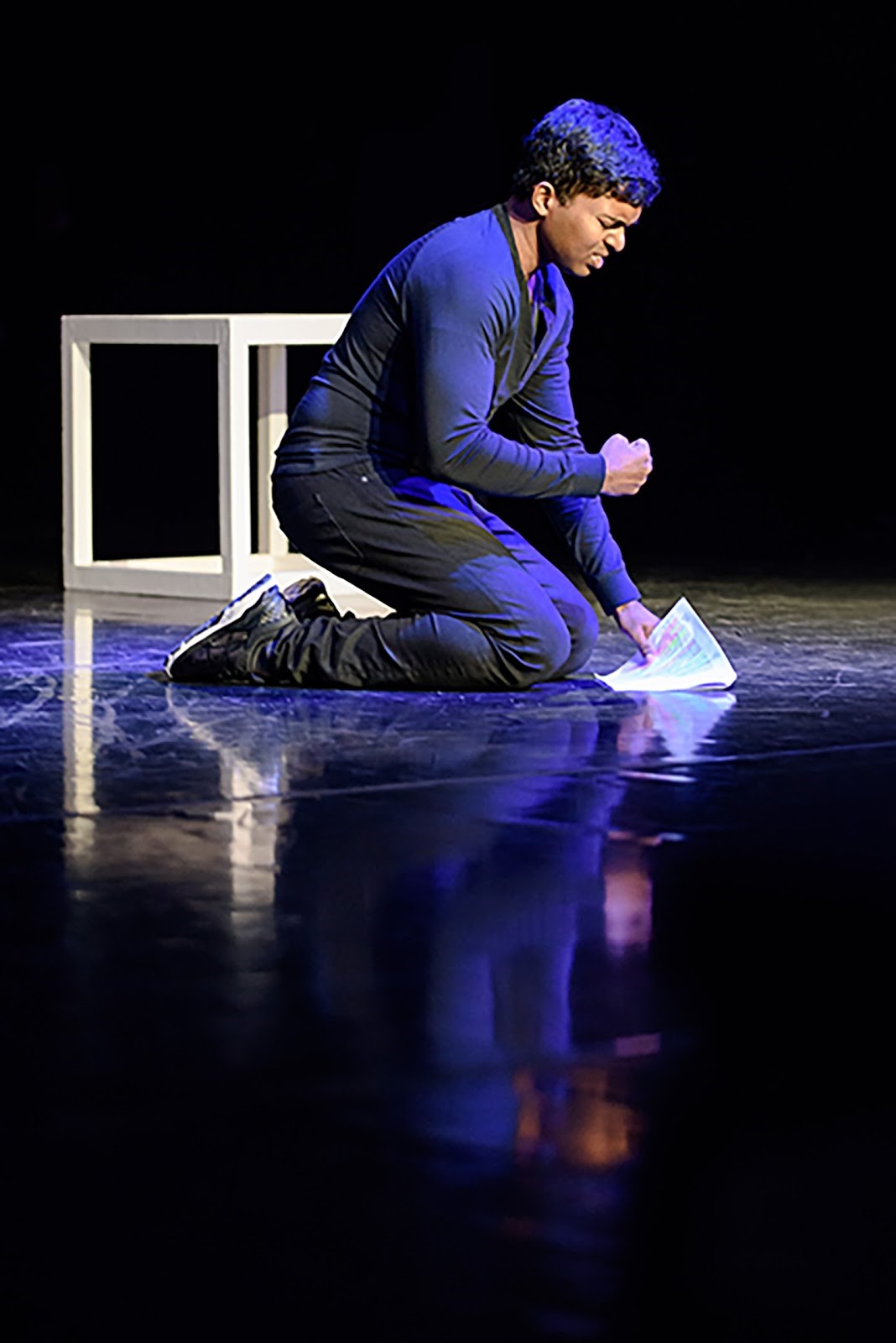

A Letter To…《至_____》by Wang Liansheng (2013)

Similar to Private Dancer, A Letter To… was also presented in the form of a monologue. The actor skillfully splits the skit into three different storylines: first, he is a husband grieving for his wife, next, a son recounting his relationship with his father, and finally, an actor performing a monologue about acting.

The three different roles overlap. The actor’s passion for acting is at odds with his father’s aspirations for him to find a more conventional and stable job. While still at his 9-to-5 office job, he meets his future wife during a smoke break. His wife is a lawyer who later goes to Mumbai for a business conference. This references the 2008 Mumbai Bombings where a Singaporean victim was held hostage and killed in the terror attack.

The monologue switches fluently between English and Mandarin in order to best portray the character’s various, conflicting identities. This is also evoked through the Chinese translation of the play’s title. When speaking to his father (or when trying to convince people in the audience who may hold similar beliefs) he does so in Mandarin in an attempt to appeal to their emotions more easily.

As we are brought through the character’s conflicts with different versions of himself, it becomes clear that this play is an exploration of how vulnerable he feels within his family, and with himself.

Two Men Peeing by Wang Liansheng (2018)

In this play, two men have a conversation in the locker room after their spin class. One of the men excuses himself to relieve himself in the toilet – the other does not mind but soon becomes confused by the lack of any noise whatsoever in the toilet.

Curiosity gets the better of him and he decides to ask his friend about this strange silence. It is revealed that the reason behind the silence was that his friend urinates while sitting down – a strange and humiliating idea to him. The two friends begin to banter about why men should or should not try to urinate sitting down, with one friend very supportive of the idea, raving about its benefits while the other struggles to accept the idea.

Overall, Two Men Peeing was a stark contrast to the more serious and intense tone of the other plays, adding a welcome touch of humour by providing a cheeky glimpse into two men’s conversation about what it means to be “manly”.

Post-show dialogue

(From left: Moderator, Director Rei Poh, Playwrights Wang Liansheng and Damon Chua.)

When the engaging and compelling performances came to an end, the playwrights and the show’s producer engaged the audience in a post-show dialogue, where they were asked about their inspirations and themes behind each of their play.

Question: How did you respond to the theme, “If We Dream”?

Damon: We wanted to explore masculinity; so you know, the pieces from my past dealt with pressures that were imposed on the male individual. Because I was writing within that theme but also responding to Liansheng’s piece about the Mumbai bombing, I wanted to showcase the perception of somebody who shows some aspect of vulnerability, such as crying.

Liansheng: So for me, it was the other way round, because Damon talked about the societal pressures that a male character would face. It was quite clear in 1995 that they were dealing with the choice between passion and the practical choice of a livelihood. So I thought – what are the issues a modern man would face, and the societal pressures?

There has been a lot of movement against men. What should I write about? Maybe I should write about peeing! And also because I had some conversations with some friends – again, a lot of the conversations come when I have food and conversations.

One of my friends shared about how he was sitting down to pee, and how it helped his relationship with his partner. And that was the story behind Two Men Peeing.

Question: Between the pieces in the past and those you wrote in 2018, the moods are very different – for example, the earlier pieces were “angstier”. Is this a reflection of how your views on masculinity changed over the years?

Damon: I was much younger in 1995. Again, I agree with Liansheng that those were pieces that were written for a series of plays which talked about how Singaporeans were responding to the pressures of being Singaporean.

Whereas nowadays, given that I am not so responsive to the issues of Singapore since I am not based here, I am much more responsive to interpersonal dynamics. The last pieces reflect more of what I’m interested in now. It is really a change of time and space.

Liansheng: When I wrote my piece in 2013, a struggle I had was with the vulnerabilities of men. I wanted to show how it is not wrong to show your vulnerabilities and your emotions. If you’re familiar with the Mumbai bombings – which was the first time a Singaporean was involved and killed in a terrorist attack – they caused quite an impact to me when I was younger. I started to follow her husband’s postings on Facebook and etc. It was actually very open, he was just sharing about how he was grieving for his wife. That got me very affected and I wanted to write about that.

Fast forward five years later, my views about masculinity are a lot more nuanced as I no longer want to present my own voice about what masculinity is to be: which is why Two Men Peeing leaves enough room for people to think about it. Also, I want men who claim that they are feminists to think and negotiate with themselves about the issue of sitting down peeing, and I didn’t force my views on it. I think how my views changed is that it went from very strong views about what I wanted to see to what I want to do now.

At this juncture, Damon takes the microphone and decides to turn the question onto the show’s director, Rei Poh. Much to the amusement of the audience, Rei steps out from his hiding place in the last few rows of seats and approaches the front. Damon asks whether he saw a vast difference between now and then, or a continuation between the past and present when directing each of their works.

Rei: When I looked at it, there aren’t many differences between the past and present. What we are facing back then is still happening right now, just that our attitudes towards it have changed. If you see the arts as a mouthpiece to comment on the mood of the society back then, I suppose that the situation back then was more serious, and people were more aggressive about their views. Now, we look at it through the lens of humour. I do have a feeling that it is going to change again, given recent happenings. That is going to change the way we write again.

At its core, past//present, was an exploration into the relationship between masculinity and vulnerability, and how it changed between the back then, and now. Ultimately, the individual stories presented by each of the five works kept the audience at the edge of their seats. With Damon and Liansheng writing new works to respond to each other’s older ones, the arts remain very much alive and changing. If you are interested in watching thought-provoking and thoroughly heartfelt productions, do catch Liansheng’s works!