In 2023, 4 NUS Students decided to compete in a Japanese-language mooting and negotiation competition.

INC Sophia is a mooting and negotiation competition held annually at Sophia University in Tokyo, consisting of both English and Japanese Language components. It is typically contested by law schools in the Asia-Pacific region. While NUS Law typically only fields teams in the English component, last year, 4 students decided to take on the unique and somewhat insane challenge of competing in Japanese as well.

Their experience, I think, highlights the capacity of us as students to take on unique opportunities and excel in them, and perhaps makes us reconsider what success as a university student could look like. For that reason, their story is one worth telling here.

This is part 2 of a 2-part story. Read Part 1 here.

“Would you say this was something of a week from hell?” I asked.

“Actually, it was the best week of my year,” Karen replied.

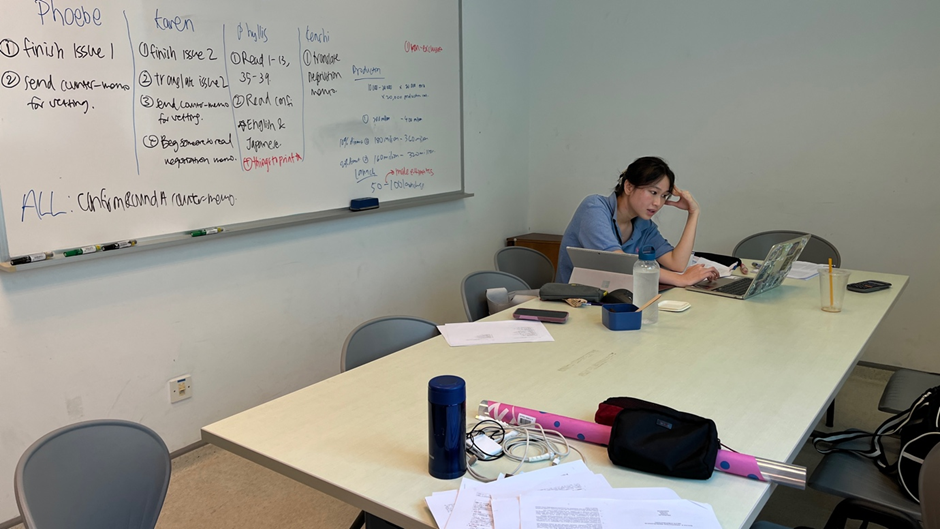

After the end of Karen’s finals, was when the rush of competing in INC Sophia truly kicked in. She had completed her exam on 1 December. Within 4 days, the team would have to write a 2-page rebuttal memo to their arbitration opponents’ memo and write a 12-page negotiation memo, all in Japanese. The day after, they were scheduled to fly off to Tokyo, and 2 days later was the start of their competition. They had not written a word of both memos, nor had they properly conducted any benching sessions. They were also not at full strength because Phyllis still had her Contract mid-terms and was not able to assist.

All of this and they were 7 days out from the competition.

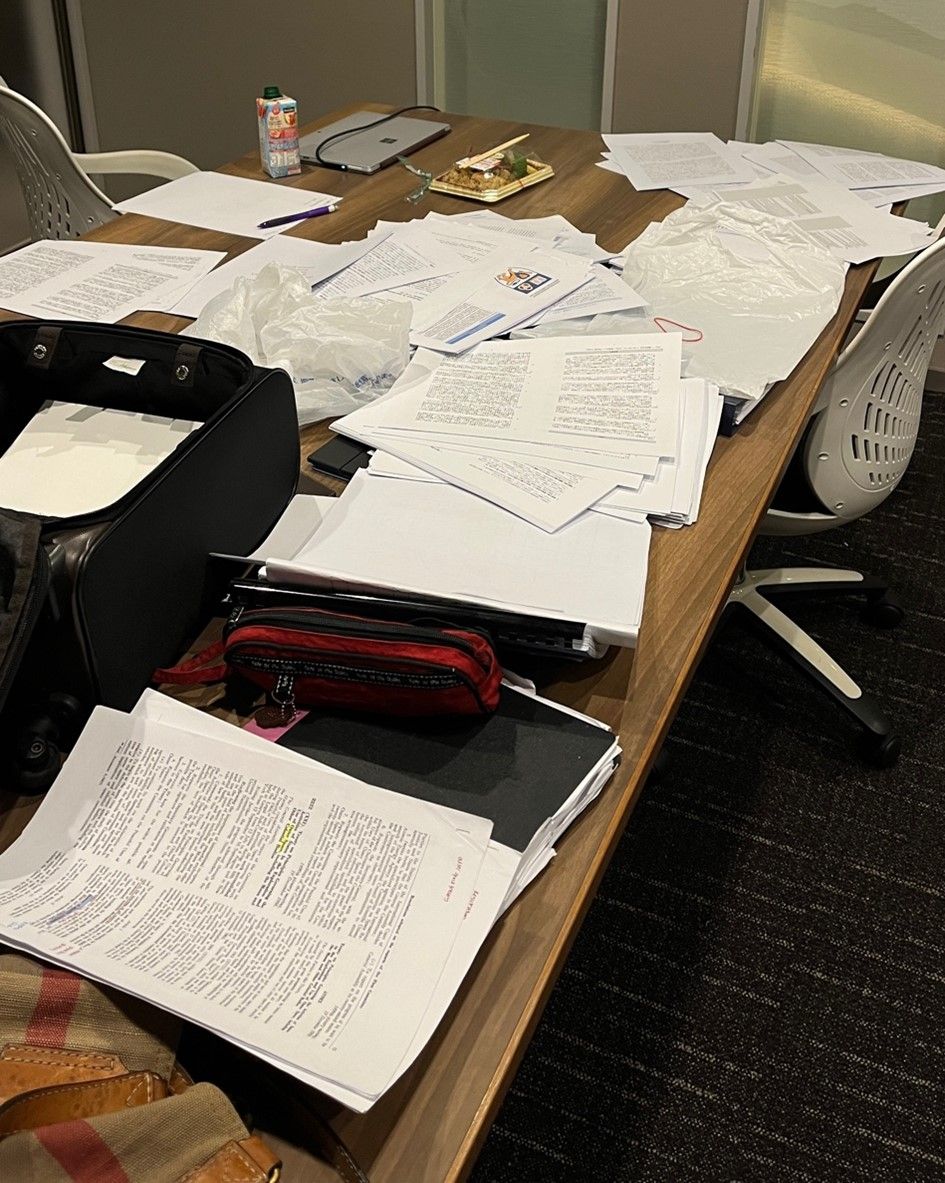

Their initial plan was a good one: spend just a day writing their rebuttals before focusing on the negotiation component, reflecting the 50/50 scoring weightage between the 2 components. But this did not come to pass. They instead spent three of the four days they had on the rebuttal memo as they once again struggled with translation issues. By 4 December, the team realised they would have to pull an all-nighter at BTC to rescue their memos.

Consider the context: this was at the end of a long semester of constantly working on their arbitration memo (as seen in Part 1) and finals. Everyone was exhausted. To make matters worse, Karen made the ill-advised decision to go clubbing a couple of nights before (“She just refuses to compromise on anything,” interjected Phoebe, rolling her eyes).

Karen had bought the tickets way back in October when she had assumed their preparation would be more well put-together and her finals had just ended, but what happened was that she ended up trapped outside The Marquee at 2 am due to road closures for the Standard Chartered marathon. She then somehow managed to crawl her way back home at 4 in the morning to continue working on the INC Sophia memos.

As anyone who has pulled an all-nighter would know, these were occasions for strong emotions and big surprises. Opening their negotiation confidential for the first time was a big shock for them, as they were promptly stumped. This resulted in a panic call with Prof Sam Tang.

“We didn’t even know what the negotiation problem was asking of us,” Phoebe related, “we couldn’t even find what the dispute between us and our opponents were.”

As they worked desperately into the night, a second surprise arrived. This one was far more pleasant, with their mutual friend Kimmie Tan showing up unannounced with bags full of Tiong Bahru Bakery pastries.

With the encouragement of these delicately crafted confections, they completed their memos in English at 5 that morning, before somehow managing to translate all of it into Japanese by the deadline at 11 a.m.

But that was only the beginning. After trying to catch a few hours of sleep, the team rushed down into the city for their first benching session the same evening, trying to cook up a passable script along the way.

It was a disastrous spar. It turned out that it was not really possible to ‘wing’ a legal oral submission in a third language on the fly with 2 hours of sleep. It was so bad that Prof Alan could not really give any feedback except to ‘prepare more’. But there was little opportunity left to do so.

The next morning, Phoebe flew off to Japan, barely managing to pack her clothes in time. Kenshi, Karen, and Phyllis were scheduled to fly off in that same evening, but managed to squeeze in one more benching session at a Japanese Big Four Law firm. This time, they performed somewhat better, and even attracted praise from the associates there for having the courage to compete in a foreign language. With the commendations ringing in their ears, they rushed back home to grab their luggage.

Karen was running late when she received a text from Prof Alan.

“Have you printed your bundle of authorities?” he asked.

“Yes,” Karen replied. She paused. “We didn’t print out the PICC commentary though.”

For context, the PICC commentary was a 400-page Japanese legal commentary on the governing law for their arbitration round.

“Print it.” Prof Alan shot back, with such an air of finality about it that Karen could feel the sternness through her phone screen.

Karen’s Grab driver was waiting for her, so she ordered her younger brother to print out the document. And so it was that Karen waited with an increasingly irate Grab driver, as her brother ran from the printing shop with a 400-page legal document, placed it into her open luggage on the floor, and off she went to Japan.

Japanese (mis)adventures

The sun was just about rising when Karen and Kenshi touched down in Japan the next morning. Kenshi, however, was not. He slept poorly on the plane, and in general, he had never gone so long without a proper rest. Bleary-eyed, he trundled up to Karen at the baggage claim.

“Have you gotten all your luggage?” he asked wearily.

Karen was holding on to a single tiny backpack that she hand-carried onto the plane.

“Yes,” she replied sarcastically.

Kenshi blinked for about five seconds. “You mean you managed to stuff all your clothes into that backpack?”

Karen was exasperated. This man was gone. ‘We are so screwed for this competition’, she thought.

It must be noted that at this point, 2 days out from the competition, the INC Sophia Japanese team still had not written their oral submissions yet. The logical action for them upon touching down would be to get caught up on their sleep, maybe have a nice meal, and start working on their problem with a fresh mind. But in the same way that people suffering from hypothermia have the sudden urge to tear off their last warm clothes just as they are about to freeze to death, the team decided to explore the neighbourhood around their hotel.

To clarify, they were not going about seeing the sights or living life to the fullest. Rather they wandered in circles around their Yotsuya neighbourhood for hours on end. It was only after Prof Alan and Prof Sam brought them out for dinner that night, and forced them all to eat something, that they seemed to regain some human function. Obviously, that was not a productive day for them.

By the next day, the enormity of what they still had to do hit them. They still had to write their oral submissions and plan for their upcoming negotiation, with their competition starting in 1 day. Thus, they hunkered down in the meeting room of their hotel to try and crank out their submissions in Japanese.

For Phyllis, she had never even written a submission in English before, having just completed her stat memo in LARC. Yet she took the challenge of writing the opening and closing statements on gamely, basing what she wrote off her teammates’ work. She felt bad for the fact that she had been absent for large parts of the preparation process and was determined to scale the steep learning curve facing her as quickly as possible.

Although working on submissions was a grim and wearisome task, it was not as though the team did not have a good time. Nor were they always particularly focused on their task.

One of Karen’s friends brought his shiba inu down to the team’s hotel for dog-petting therapy in the middle of the afternoon. Karen then went on a 2-hour ‘mental health walk’ with said friend and dog. This meant that by 6pm the night before the arbitration round, Karen’s script was only half-written, and the team’s negotiation prep was non-existent.

But Karen had had enough.

“I can’t do this any longer,” she told Prof Sam.

Prof Sam replied, “Well, I’m going out for a drink.”

And so, Karen left the hotel to join Prof Sam at a bar. Phylllis tagged along as well. That bar was no ordinary bar—it served an exceptionally smooth sake which had a royal warrant on it, meaning that they were literally consuming drinks fit for an emperor.

Of course, that did nothing for Karen’s productivity, whereupon returning from the hotel went for a late-night Kombini run with Phoebe, followed by a 2-hour heart-to-heart talk with her. That meant by 6 am of the day of the competition, and yet another night of little sleep, Karen still had not written her oral submissions.

What happened next was a frantic scramble on Karen’s part. But while such a lifestyle was probably not the best for Karen’s physical and mental well-being, it somehow seemed to work for her. As her mind went into overdrive, the difficulties, and obstacles in writing the script seemed to magically melt away, and she completed the script that she was struggling with for days in 15 minutes.

Competition Day 1: Playing in an Away Game

As dawn broke upon the first competition day, the INC Sophia Japanese team was utterly exhausted. They had put in a great deal of effort just to get to this day, but now they actually had to moot in person. The team were literally playing an away game, with so much stacked against them. They were playing in a foreign country, the home turf of their competitors, in their language, and with the judges all from said country. And this was the first time they, or anyone from NUS Law for that matter, had ever done something like this.

“Historically, NUS in sending English teams has become comfortable with uncertainty as a source of advantage - the confidence to bulldoze most opponents with sheer language ability,” Prof Alan explained, “The Japanese team [was] basically in the opposite position: uncertainty becomes disadvantage.”

Prof Sam added, “I cannot imagine sane law students from other law schools deciding to do this on their own”.

Indeed, most foreign teams who participated in the competition did not send a Japanese team. Team Australia used to. But they were a well-oiled machine. They had a pre-competition, a special selection process from all Australian universities, and institutional support. And they gave up on sending a Japanese team this year. Team NUS’s Japanese team, in contrast, was an eclectic jumble of personalities that were running on fumes.

Quite literally so, as Karen downed six cups of coffee at one go before the competition.

But all the team members had a rather indomitable spirit because their experience had already been so unique that they did not care, or expect, to win the competition.

So, they just had fun.

Most of their Japanese competitors reacted with surprise when they saw the Singapore team. They usually reacted with some variation of, ‘Why would you choose to put yourself through a legal competition in Japanese?’ But the tone was generally one of friendliness and collegiality, being more than willing to make friends and exchange contact details.

Karen was speaking to one such female competitor during one of the competition’s socialisation events, who she could not help but notice was rather attractive and well put-together. The competitor however, had a very unassuming demeanour. It was only after exchanging social media details that Karen realised that she had a verified Instagram page and tens of thousands of followers. The competitor that she was talking to had been the winner of ‘Miss Kimono Japan’.

For the arbitration round, the NUS Team went up against Osaka University, one of the top law departments in all of Japan. Despite the apparent mismatch in abilities, the NUS team more than held their own. The scripts that they had prepared quickly went out of the window, with legal questions coming thick and fast from the judges, while simultaneously rebutting ir opponents’ points.

But somehow, all of them managed to give strong and coherent responses in Japanese.

There was a particular moment in the round that stood out, when the NUS team sought to back a point in their legal argument. It was a technical point on the probability of ‘G4’ space storms occurring, and the NUS Team cited an English-language research paper to support their point, and their opponents had no response. The research paper had never been published in Japanese. It was thus the melding of their expertise in both languages that allowed them to perform during the competition.

At the end of the round, each team had 15 minutes to prepare a closing submission that summarised all the points covered during the round. Karen, Phoebe, and Phyllis had taken notes during the round, in a mix of Japanese and English, and passed said jumble of points to Kenshi to translate into a coherent Japanese submission. For a moment, Kenshi looked at them in shock, his eyes glazing over. But that moment passed, and he quietly but steadily translated it into a coherent Japanese script. It would have taken him 4 or 5 hours less than a month ago, but his abilities had improved to the point that it just took him minutes.

“[Kenshi] was reliable throughout,” Prof Alan commented to me.

“But he kind of became the punching bag/saikang warrior for the entire team, true to his Hwa Chong roots,” he added.

Despite having given the NUS team a hard time during the round, the judges were full of praise for all of them at the end of the round. In particular, they were impressed by the team’s courage and gumption to put themselves through competing in Japanese. One of the judges even personally gave his name card to each of the team members afterward, telling them to ring him up if they ever wanted an internship in Japan.

Competition Day 2: Going down in ‘a [moderately] expensive, fun blaze of glory’

By their own estimation, the team had done rather well for the arbitration round. But it was also true that they had spent a ridiculously disproportionate amount of time on their arbitration round at the expense of their negotiation preparation. Reaching back at their hotel after an incredibly busy day, in an incredibly busy week, in an incredibly busy month, and in an incredibly busy semester, they had yet another late night to look forward to.

They did manage to get through about a couple of hours of preparation, but Karen could not take it any longer. She had been dialed up to eleven for a long time and the adrenaline had drained out of her after the arbitration round. She told her teammates that she had to get some sleep and suggested getting up early at 6 the next morning to continue their preparation.

Karen did not get up at 6. She crashed that night and slept through all her alarms, eventually getting up at 10.

The negotiation round was slated to begin at noon.

Additionally, they all had to check out of the hotel that morning, and she had not packed.

Thus, as was characteristic for Karen at that point, she had to go into a frantic rush. Fortunately, they did somehow manage to pull out another minor miracle, and completed their negotiation preparation in time, although they felt it was far from the standard of their arbitration preparation.

Arriving at the competition venue, a special feature of this negotiation round was that each team had to present their negotiation plan to the judges, something almost like preparing a pitch deck.

Their opponents, Meiji University, had prepared an incredibly slick, unique, presentation that one of the judges later described as “possibly the best presentation I have ever seen.”

The NUS Team, meanwhile, only had a PowerPoint presentation which they cranked out in less than 10 minutes that morning..

It was not the best of starts.

The round did not go particularly well, either. The Meiji university team had thought through what they wanted to do. They began the negotiation round by presenting to the NUS team on a piece of paper a list of proposed outcomes for the negotiations. When the NUS team rejected it (as they should), pointing out a whole list of unaddressed concerns, the Meiji team merely smiled.

“Ah,” one of them said calmly, “we have a solution to that.” And he pulled out another piece of paper with an alternative set of solutions that conceded most of the contentious points to them.

It was not easy to negotiate because while one could prepare submissions and anticipate likely questions for an arbitration, doing a negotiation required spontaneity. That was difficult for the team to do in Japanese. Particularly, they needed to get the right honorific registers in addressing their opponents, while utilising a different one for themselves. Trying to do this while balancing four or five technical points on the intricacies of satellite launch agreements required quite a bit of mental gymnastics.

Furthermore, the NUS team was not prepared for an opponent that was quite so pliant. The Meji team were incredibly polite throughout, speaking very slowly to make sure that the NUS team could understand and follow the conversation, while the NUS team spoke slowly out of necessity. Yet they had come to an agreement half an hour before the negotiation was scheduled to end. The judges seemed surprised.

“I have never seen a negotiation go quite so well before,” one of them commented.

The Results

At the end of the competition, all the competitors and coaches filed into the auditorium where the results would be announced. An old Japanese man walked on stage to announce the results. The individual category results, which were grouped by language, would be announced first.

The Japanese language categories for best arbitration and negotiation performers were announced, both won handily by Japanese universities. No surprise there.

The NUS English teams hoped to win at least one of the English language categories. As always, the NUS English teams had done rather well. Winning one of the English competition categories would thus be an important signal as to how well all the teams did overall and might even be the only chance to have some sort of showing in the competition.

They did not win.

That was not a good sign, and most of the NUS competitors began to have the sinking feeling that NUS might return empty-handed for the first time.

Not the Japanese team though. “We had absolutely no expectations,” Phoebe said.

Now came the overall scores.

“Seventh place goes to….Meiji University!” the old man exclaimed.

Seated several rows from Phoebe, a young man burst into tears. He was the coach for the Meiji University team,

That was the team that the Japanese team had gone up against for the negotiation round, and it was an opponent that they had thought they had done badly against. If they had gotten seventh, Phoebe thought, that was probably it for NUS’s chances.

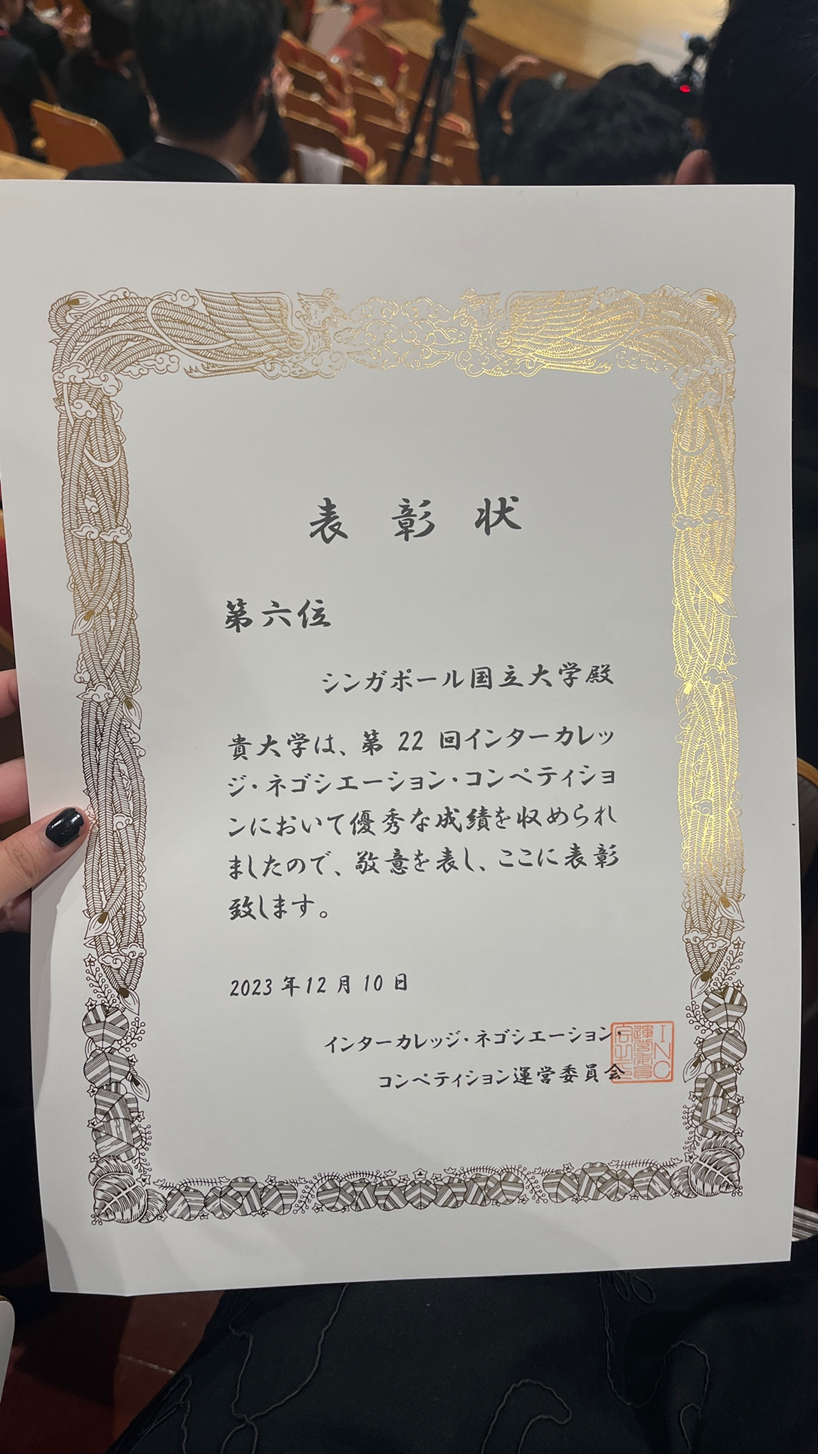

“And in sixth place, it is…..” the old man paused for dramatic effect, “National University of Singapore!”

A single hoot of joy came from the crowd. That was Prof Sam. Everyone in the auditorium looked at her in surprise before resuming their polite applause.

As for the NUS Japanese team, they were simply shocked. Not shocked out of joy or disappointment, but just shocked in general. “We had managed to place in the competition?” was the prevailing thought.

They were all still in a daze when an announcer called for each team to send a representative on stage to give a thank you speech. Before he knew it, Kenshi found that he had been arrowed to be NUS’s representative and stumbled onto the stage. Under the bright glare of the stage lights, he suddenly heard someone shout from the crowd.

“Do your speech in both Japanese and English!” it shouted. (It was later found out during the process of writing this article that it was Phoebe who shouted that).

Kenshi had not prepared anything to say, but ever the reliable man, somehow belted out a perfectly composed speech in both Japanese and English.

“Is this how reliable people do it?” Prof Alan commented, “Their screw ups work out great?”

Great Expectations?

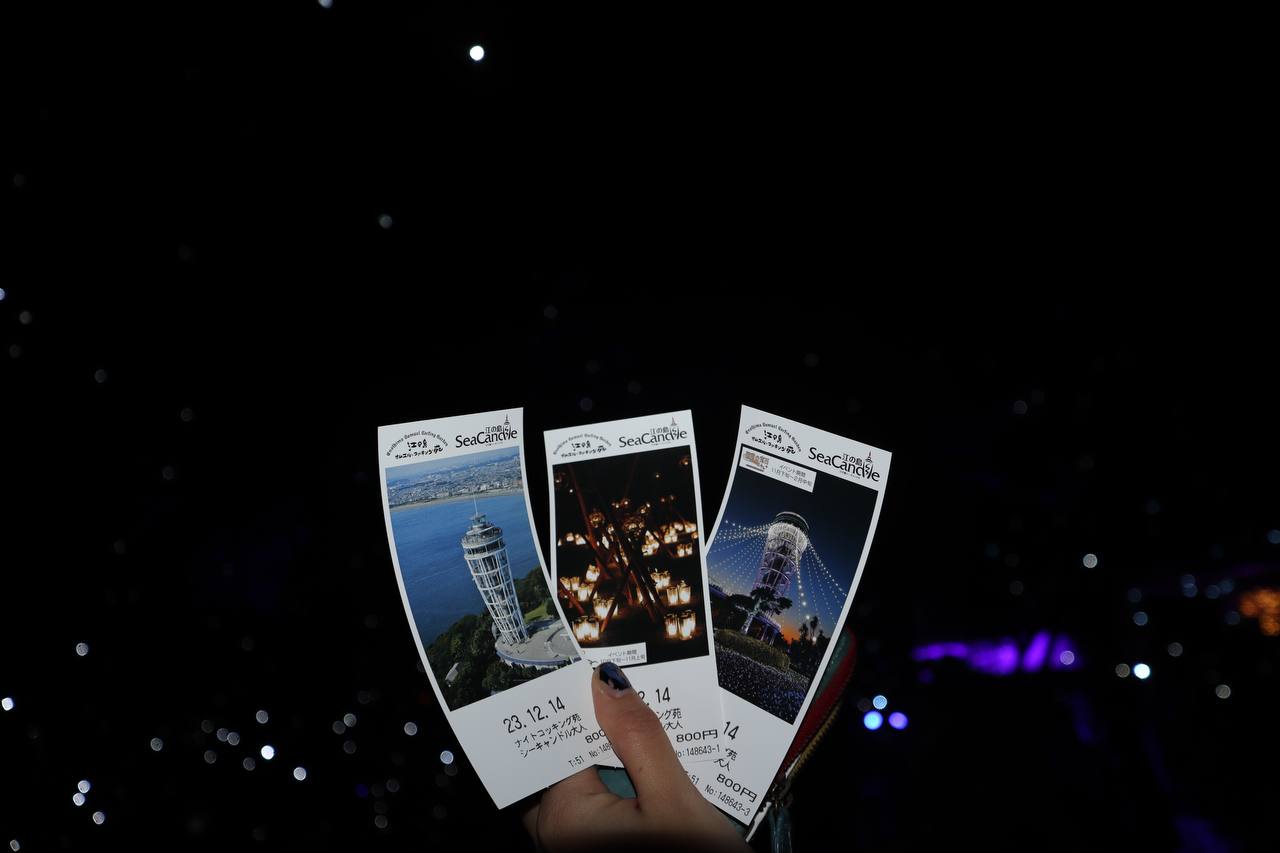

By the time I had met the INC Sophia Japanese team to interview them for this piece, nearly a month had passed since the competition. They had just returned from their holiday in Japan (“It was so fun” Phoebe exclaimed. “Kenshi regretted extending his trip to Japan only by a week,” Karen interjected), and they all had some time to reflect on their experience.

6th place, objectively speaking, was not a particularly great result, by the past performances of NUS at the competition. And that ranking belied the fact that the English teams had pulled up the overall score. Or to put it more bluntly, the Japanese team’s scores pulled down the English team’s average.

“If we had competed solely in English and we had gotten 6th, yes, obviously we would be disappointed,” said Phoebe, “But the fact was that we were doing something completely unprecedented, and with such a disadvantage, competing in Japanese, that I did not have any expectations on result going in. I think all of us were really there for the experience.”

“Although I do feel a bit bad for the English teams this year…” her voice trailed off.

Throughout the preparation for the competition, the Japanese and English teams never interacted much. Only after the competition did they start to get to know each other. They all had positive impressions and experiences with each other in the post-competition celebrations, but I did sense an undercurrent of unease on the issue of the results.

But perhaps I am being too harsh too. 6th might be considered an underperformance by NUS’s past record, but that was also because its record had been almost unnaturally stellar. Many of the other competitors considered any form of placement in the competition a good result, and I learnt from Karen later that when the Meiji University Team’s coach burst in tears hearing that his team had gotten 7th, they were tears of joy rather than sadness.

When valuing a particular experience, perhaps it is easy to just look at the top-line and bottom-line numbers: how much time, energy, money etc. did one invest? And what was the return on that investment? With a law school competition, it might be: how prestigious is the competition? And what is the result achieved?

All of the team members readily admitted that if this was a ‘normal’ competition in English, they would have to place well for the experience to be a success. Of course, they emphasised, a competition in Japanese was different. It was the first time they were doing it, and they were building the foundations to do better next year, they assured me. But it was also true that with the expectation that they had to do well taken away, the team had found the room to have fun, and live in the moment fully. They did the competition out of their love for the experience of competing, their love of improving their proficiency in the language, and even of learning a new area of the law.

I tried to probe a little further. After all, our conversation over the last few hours had gone well. And sitting in that U-Town Starbucks, it just felt like one of those afternoons where anything was possible, where a new, crazy, idea could just sprout forth.

Did they think this competition had changed their approach to life?

“100%” Phoebe responded without hesitation. “After the competition, I could feel there was a big change in me. The fact that we could do something crazy like this taught me that I don’t have to fear so much. I mean,” Phoebe paused. “I learnt Japanese without any connection to the country. I just did it because my sister wanted to learn it and I just tagged along for fun. So I was always afraid to speak the language to someone else because I thought ‘this isn’t my language’.”

“And I always assumed that yes, learning Japanese may be good for my CV down the line or something,” she continued, “but I had so many experiences, both positive and negative, because I had made this leap, and what I realised is that the point is to use what I am learning now, and to do the best I can now, imperfect as it is. So I have, for the first time, genuinely considered ways I can use Japanese in my future career, to explore getting a job in Japan and all that. Even if I stumble and fail, well that’s the point, isn’t it?”

For Kenshi, the experience seemed to be the impetus for him to pursue his Japanese language ability at an even higher level. He had witnessed in full force, the Japanese legal world, and he realised that he wanted to get to know more about it.

“I was thrown off the deep end,” Kenshi said, “but it also gives me more confidence in the future and more impetus to perfect the language.”

Phyllis had quite the adventure in her first semester of law school, with more ups and downs perhaps, than many might go throughout their entire university life. She hoped that the future would be just as exciting, although hopefully not quite so terrifying. Either way, it was an experience to remember.

As for Karen, before INC Sophia, she had gone through law school largely rudderless. Her grades were not the best, and they had begun to weigh on her.

The competition, however, had given her a new spring in her step.

“This competition really affirmed for me that I can still like the law even though my grades are bad.” Indeed, it was more than that, she had showed she was a fantastic organiser, an incredibly hard worker, a great memo writer, and she did something many of her more academically accomplished peers would hesitate to touch.

Prof Sam Tang concurred in written texts, “I have a newfound appreciation for the crazy things our students do—and you really don't have to be on the dean's list to do absolutely amazing things in law school.”

She also added, “It's always very funny to me how our students can simultaneously underestimate their own abilities ("Oh no, Prof we are going to fail our exams." Oh, please.) and overestimate them ("Prof, we totally know enough Japanese to tackle at 60+ page hypo, write our submissions and talk to Japanese people using legal Japanese despite not being very good at Japanese let alone kanji") at the same time.”

Karen fit the bill for Prof Sam’s description perfectly (I suspect it was directed at her). At the end of our interview, she proclaimed, “I know I have no right to say this, but I am honestly excited for Year 2 Sem 2.

She paused, “Although based off my grades I should be thinking about dropping out!”

Her teammates around her all collectively rolled their eyes.

Author's endnote: I would very much like to thank the NUS INC Sophia Japanese Team, as well as Profs Alan Koh and Sam Tang for being so forthcoming and open in sharing their experience, and especially to Karen for her help organising the article. All photos and videos (except otherwise stated) are credited to the team.