The full transcript of the Singapore Law Review Lecture can be found on the Singapore Law Watch website here.

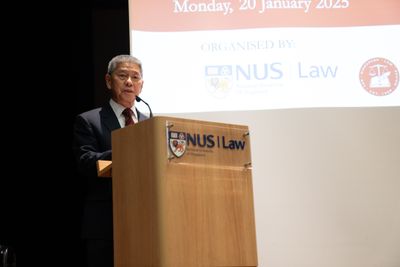

For one and a half hours, the Honourable Chief Justice, Sundaresh Menon captured the attention of the packed Moot Court with the fascinating topic of “The Interpretation of Documents: Meaning What They Say and Saying What They Mean“. The lecture covered Singapore’s approaches to contractual and statutory interpretation, as well as areas in which the law is as yet uncertain. Quotes from everyone’s favourite Lord Denning were also thrown in for good measure.

The Singapore Law Review Lecture (“SLR Lecture”) was started in 1984 to raise the profile of the Review and attract good students onto the editorial board. (Kevin Tan, 10 Years of the Singapore Law Review (1993) Sing L Rev 24, at 38)

Esteemed judges, academics, students and many others from the legal profession gathered in the moot court on 10th September 2013 for the 25th Singapore Law Review Annual Lecture, delivered by Menon CJ. The lecture marked the 30th anniversary of the revival of the Singapore Law Review, coincidentally initiated by the CJ’s batch-mate at NUS, Prof Kevin Tan.

Back in 1984, the s 9A of the Interpretation Act was not in existence and it was more than two decades before Zurich Insurance. In this context, it made sense, then, to focus more on proper drafting, so as to avoid the prospects of expensive litigation later down the road. However, even a well drafted law has its problems; the shortfalls of the literal approach are well documented, resulting in courts taking on more proactive roles in interpretation.

Menon CJ shared his observation that “the law has evolved from a literal approach, to what is commonly known as the purposive approach (in statutory interpretation) and the commercial or contextual approach (in contractual interpretation).

As one would expect from a common law jurist, Menon CJ started his lecture by reiterating the central role of the objective approach in the common law tradition. The objective approach “shift[s] the burden … [to] the contracting parties to ensure at the outset that their respective subjective intentions are accurately encapsulated within the four corners of the legal text”. The inadequate discharge of this burden was however immediately acknowledged as an inevitable source of interpretative dispute. “The imperfect mind, bedevilled with imperfect foresight and knowledge, and subject to economic constraints, directs the drafting of a legal text using language that is inherently imprecise.”

The economic analysis in particular merits attention. It is an acknowledgment that parties cannot be expected to contract for all possibilities. By deliberately leaving some portions open, parties are taking the risk that those issues will not result in protracted and expensive proceedings. The author however submits that courts should not hastily jump on this contracting impossibility as a justification for taking on a more hands-on approach. When parties make the conscious decision to leave certain matters out of a contract, they depend on the court to adjudicate not just on the fairness, but also according to their reasonable expectation of the result at the time they took the decision. While it may be fair to take into account matters such as commercial context, this should not come at the expense of certainty. Indeed, it is acknowledged that the two do not necessarily conflict. The point to be made though, is that courts should err on the side of caution and exercise the appropriate self-restraint in not departing too far from written contracts for the sake of commercial fairness.

Menon CJ justified Singapore’s higher threshold of “necessity” by highlighting the differences between interpretation and implication, with the latter involving some form of rewriting of the contract.

After establishing the need for the purposive and contextual approaches, Menon CJ then considered the approaches in detail. Of note are the limitations of these approaches. While both approaches try to give effect to the purpose/intent of the drafter/parties, the commercial context is more contentious because Singapore has departed from the UK analysis of the extents of the contextual approach. The question of implication of statutes was however left open, though a lower threshold may be possible since, as Menon CJ noted, parliamentary intention can be ascertained much more easily.

Menon CJ’s lecture seems to indicate that the burden of the cost-benefit analysis has been shifted onto the courts. For instance, in the context of statutory interpretation, ‘the courts should have regard to “the desirability of persons being able to rely on the ordinary meaning … taking into account its context … and the purpose or object underlying the written law”, and also, “the need to avoid prolonging legal or other proceedings without compensating advantage”‘. Whether prior negotiations should be admitted as evidence was also described as a balancing act between the cost and benefits. These do not suggest, however, that parties can abdicate their responsibilities of drafting adequate contracts (and there is indeed no incentive for them to do so). Rather, the statements serve as a reminder that the courts, with their significant discretion in the interpretation of contracts, must also take a measured approach in discharging justice without compromising on efficiency, and vice versa.

A number of students signed up for the event but many practitioners, who were given priority, showed up in droves.

This writer may be too unlearned to fully appreciate the content of the lecture. But from the little that he could gather, it is safe to conclude that Menon CJ’s interpretation of Sembcorp Marine v PPL Holdings could give contract Profs Mindy Chen-Wishart and Goh Yihan (both of whom were in attendance) a run for their money. After all, the man wrote the book (judgment) on it.

The Chief Justice understandably chose to reserve his thoughts on some outstanding issues. It is noteworthy however that the live issues he highlighted, such as the admission of prior negotiations in contractual interpretation, the use of expert evidence in establishing commercial context and the expansion of the contractual approach to other areas of contract law in the UK, were all concerning the further liberalisation of existing rules. This suggests that future debates in the area of interpretation, at least in the Singapore context, will likely be centred on increased liberalisation.

Our esteemed dean in some highly esteemed company.

Participants were treated to a generous buffet reception after the lecture, courtesy of long-time SLR sponsors, KhattarWong LLP. Menon CJ, Chao Hick Tin JA, Vinodh Coomaraswamy J, and Lionel Yee JC also stayed behind to interact with guests and students.

Familiar faces: Assistant Professor Mark McBride, Associate Professor Dora Neo and Professor Mindy Chen-Wishart sporting a new look.

Chao Hick Tin JA shares a meal and some words with Prof Kevin Tan.

Conscientious readers will be able to find a transcript of the lecture in the 32nd issue of the Singapore Law Review, which will be available in 2014.

Article by: Xing Yun (Year 2)*

Photography by: Chan Ying Ling (Year 3)

*Executive Editor, Singapore Law Review. All remarks made in this article are mine alone and do not reflect the position of the Review.