There was a sense of occasion in the air. The court waited with bated breath as the judges took their seats. Their arrival signaled that a battle was about to begin.

Cue artistic shot…

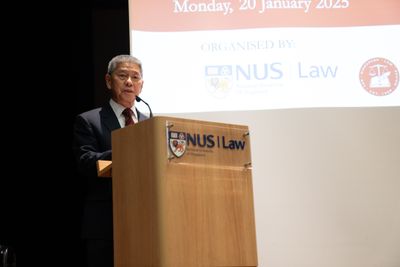

As Singapore’s only criminal law moot, the Attorney General’s Cup is undoubtedly one of the highlights of the mooting calendar, and this was evident in the turnout for the event. Audience members exercised creative measures to get a good view of the stage for the imminent clash of wits. Presiding over the day’s proceedings were three of Singapore’s legal heavyweights: Attorney-General Steven Chong S.C., Judge of Appeal Justice Chao Hick Tin and the honorable Justice Quentin Loh.

A trophy fit for the Attorney-General.

The issues for the Finals were in relation to Section 298A of the Penal Code, which prevents the promotion of disharmony between different religious groups. In this case, the accused had published an inflammatory, religious post on his U.S.-based blog, which led to the posting’s circulation by Singaporean bloggers. As a result, police reports were made by individuals from the affected religious communities. Among the sub-issues discussed were the extent of the Singapore court’s jurisdiction concerning offences committed overseas, whether the accused possessed the necessary mens rea i.e. criminal intent to constitute a finding of guilt, and whether the severity of the sentence in the original decision was justified.

Calm as clam.

NUS’ very own Sim Bing Wen, for the accused and appellant, was up first. Having to appeal against the decision of the “trial judge”, he had the unenviable task of picking apart the reasoning found in the judgment. His three submissions were that (1) the Singapore court had no jurisdiction over offences committed overseas pursuant to Section 298A of the Penal Code (2) the accused did not satisfy the requisite mens rea and (3) the custodial sentence imposed was excessive, and that a fine should be given instead.

Sim Bing Wen of NUS telling it like it is.

One would be forgiven for thinking that a discussion of the Singapore court’s extra-territorial jurisdiction might not stir excitement. Thankfully, the judges had other ideas in mind. It wasn’t long after Bing Wen had begun his first submission that Quentin Loh J interceded and asked, “If I fire a rocket into Johor that causes death, does that mean I did not commit an offence?” Was this a rhetorical question? Bing Wen himself seemed taken by surprise, but ultimately deferred to the first principle of mooting, and law school: “Answer the question!” Having regained his composure, he proceeded to reply to this curveball with the adroitness and coolness of Harvey Specter (for the less educated and the socially unaware, he is a smooth-talking lawyer on a popular American TV drama).

The judges were on fire with their questions that night.

This line of questioning would persist for the rest of Bing Wen’s submissions. Clearly, the judges were in a mischievous mood that night, so much so that Bing Wen was unable to move past his second submission before his time was up. The Attorney-General picked up on this, and indicated that the Bench, while not with Bing Wen on his first submission, did not expect him to succeed on all his points. Would this be an unrecoverable position for Bing Wen?

Liu Xuanyi of SMU pondering his plan of attack.

SMU’s Liu Xuanyi for the respondent would take his place next. His arguments were, expectedly, in direct opposition to Bing Wen’s points. Notably, his points seemed to echo many of the judge’s observations and points during Bing Wen’s submission, and to the uninitiated (such as this writer), might have seemed a tad opportunistic. Yet, in using these observations, Xuanyi’s points were organized and easy-to-follow.

SMU’s Xuanyi shared a couple of jokes with the bench.

As the representative from SMU concluded his points, he had this to say, “There has not been a day that the court has shied away from protecting national interest. Today shall not be that day.” Stylistic, definitely. Substantial, arguably. Would the judges consider this form over substance, or had he done enough to clinch this moot? The judges retired to their chambers (outside the Moot Court) to deliberate.

Such was the intense discussion amongst the audience members of the finalists’ performances that the judges’ return seemed swifter than the justice they meted out. Before delivering their choice of the winner, the Attorney-General acknowledged the contributions of the various stakeholders in the organization of the Attorney-General’s Cup and mentioned that the judges of earlier rounds had been impressed by the high standards of the participants. But if the audience thought this was praise enough, they were sorely mistaken.

The Attorney-General was effusive in his commendation of the two participants’ performance, in saying that the two finalists performed to such a “high standard that they were equipped to join the profession immediately” – words enough to put a spring in anyone’s step. The judges were unanimous in holding that they both displayed a good command of the facts and the law, engaged them the court without reference to their notes and were calm and composed in demeanor. Still, a winner had to be decided from the two finalists. Ultimately, Liu Xuanyi was declared the overall winner, with Sim Bing Wen claiming the runner-up position, while NUS was declared the overall winner of the Attorney-General’s Cup for the school’s overall performance in the competition.

Sim Bing Wen receiving the Attorney-General’s Cup on behalf of NUS.

If the audience’s thirst for knowledge was quenched by this epic showdown of wit and skill, their hunger for, well, food was veritably satiated by the buffet spread offered after the moot. Perhaps in homage to the celebrations of medieval times, this was indeed a feast to mark the end of an entertaining battle. And having witnessed the intensity, complexities and nuances involved in this moot, this writer will now be attending more of such moots — to quench his thirst for knowledge, of course.

All in all, the Attorney-General’s Cup Finals 2013 was a moot of the highest order – congratulations to all the prize-winners!

Photographer: Choong Jia Shun (Year 1)