Tan Kok Quan Partnership is a leading full-service law firm providing legal services across a broad spectrum of industry sectors. Today their firm has grown to more than 35 lawyers and continues to have a reputation for top-quality legal services, frequently garnering plaudits from clients and independent leading legal publications such as Asian Legal Business, Euromoney and Chambers Asia-Pacific.

Here we interview Senior Associates Geraint Kang and Eugene Low.

J: First of all, thank you very much for agreeing to do this interview. Firstly, could you please tell us about your firm?

Geraint: TKQP is a boutique dispute firm. Our main practice areas are commercial litigation and insurance litigation. We also offer family law and real estate law. We position ourselves as a conflicts-free disputes firm, so we pick up a lot of the high-end work where other firms may face conflicts of interest, but at the same time, we also receive equally high-end work from our core group of clients. At the same time, as we are a smaller firm we’re able to take in a lot more small files that bigger firms may turn away. This is great for young associates because with smaller files, they get a chance to cut their teeth a lot earlier (where the stakes are lower), allowing them to gain more experience, learn, and be more involved in the strategy of these files.

J: Besides the fact that your firm is able to take in smaller cases and its unique position in Singapore’s legal industry, what else is unique about TKQP?

Eugene: We place a heavy focus on growing people and people development. I know it sounds trite, but our partners bother to sit down with us to speak to us about what they think are our weaknesses and strengths. They advise us on how they feel we can improve, and on developing our careers in a direction that they think will be sustainable for us such that we will have a sustainable career the many years into the future.

We are also given a lot of freedom and latitude to do things that we are passionate about. For example, Geraint and I spoke at the seminar just now about how we are very passionate about varsity engagement and getting the word out to potential employees and law students about what TKQP stands for and what we do. The partners have given us a lot of freedom to go and pursue that direction.

Geraint: On a more commercial note, I think one thing about our firm is that it’s very forward thinking. As you might have read on the news, there have been a lot of developments in Singapore law. There’s been a big push to market Singapore as a regional hub, and at the same time we’re seeing the development of artificial intelligence which is going to affect a lot of bread and butter legal work. One of the advantages of being in a smaller firm is that our size allows us to be a lot more nimble.

Our partners are all very aware of possible developments in the future and are always thinking about how they can change the firm to adapt to any challenge that comes our way. On top of that, they also actively involve the associates in thinking about these issues – as they constantly tell us, their goal is to groom us to take over the firm so that they can enjoy their retirement.

J: We also hear that TKQP is often involved in pro bono matters. Could you tell us more about the pro bono activities that your firm does?

Geraint: We certainly encourage pro bono work. For instance, we’re actively involved in two Law Society pro-bono programs. One would be the Criminal Legal Aid Scheme (CLAS), where associates are allowed to volunteer for CLAS cases. We try to take on cases that match up with the level of experience that an associate has, and we see these pro-bono schemes as opportunities for associates to develop their skills and appear in court. The second activity that we are involved in is the Community Legal Clinic where we render ad-hoc pro-bono advice on to people who may not be able to afford a lawyer.

On top of that, the firm is very open to associates taking on pro bono work on an individual basis. Thus, for example, if some people have friends in need of legal help, the partners are more than willing to let these associates take up these files on their own.

Eugene: To add on to what Geraint said about the CLAS cases, our firm has actually given an undertaking to Law Society to do a certain number of CLAS cases a year. There are some of us who really enjoy doing pro-bono, and I make it a point to do at least one case a year. It’s a bit difficult to juggle with all our paid work, but we make an effort and the partners are willing to give us that kind of room to do pro-bono work.

J: What is the main difficulty with having to juggle your pro-bono obligations as well as your regular commercial work?

Eugene: Pro bono cases involve a lot of court work, meeting clients in prison, a lot of things that consume a lot of time. So, for every one case we take up we expect to spend, in terms of face time with the court and the client, anything from twelve to sixteen hours.

Geraint: I think basically when you take on a pro-bono case, it’s the same as taking on the workload of any other commercial file. We cannot just treat this as a side project. It has to be given the same amount of attention that you would give to any other file.

One thing that makes it easier for us to take on pro bono work is that the associates our general litigation department do not have billing targets. And so there’s no pressure to churn out a certain number of commercial hours before you can do a pro-bono scheme, but at the same time, you still have to allocate and budget your own time properly so that you have the ability to manage both your workloads.

Eugene: Yeah, and we do make it a point that when we take on a pro bono case we do it as though it is a paid case. So, whatever research we would have done for a paid case we would do; whatever submissions we would have had to make, we would make; whatever time we spend, we will spend as well – it isn’t a light workload, it’s essentially taking on a new file.

J: With all these unique features of TKQP, what kind of person do you think will fit in well at your firm?

Eugene Low: Somebody who is very driven, who wants to achieve a lot with his or her career. Somebody who works hard but plays well with others would actually find TKQP a very fulfilling place.

Geraint: I think somebody who’s flexible, with a lot of initiative. Someone who is commercial minded. We find that it’s very easy to get lost in complex legal arguments and forget that at the end of the day, your client really doesn’t care about the academic aspects of the law, he just wants to make money and not get in trouble. We like people with a broader understanding of how the world works; don’t just limit yourselves to Legal Studies, think of the world at large: what’s China going to do to our economy, what’s AI going to do to our legal services, things like that.

J: Speaking of working and playing, does work-life balance exist?

Geraint: I think Eugene and I are going to differ on this. I wholeheartedly believe in work-life balance, but if you’re thinking life balance is fifty percent work fifty percent play then there’s no such thing. At the end of the day, I think it’s important to find a sustainable career such that your work doesn’t seem like tedium. If you take pride in your work, your work can be just as rewarding as play.

On the other hand, I also believe that in order to deliver the best product you must unwind and take a break when you need to — otherwise, if you’re working tired and grumpy, you’ll just end compromising on work quality. So when it comes to work life balance I think it’s a bit more complex than trying to leave for home at six o’clock every day and watching Netflix for six hours. It really just boils down to what you want out of life, how you work to accomplish it and how well you use your time to make that happen.

Eugene and I are going to differ on this again but I think, at least for the last one year, I’ve not pulled any all-nighters. In fact, I’ve only done one … no, two all-nighters in my entire legal career, and both times I think it was really down to poor planning on my part rather than something I was forced to do.

J: When you say all-nighter, how late do you mean you stay until? How often do you have to stay late? Does that affect your work-life balance?

Geraint: You know, find flexible hobbies where you can just pick up and do at any point in time. Sometimes, you could be lucky: your client calls you: “Hey, I’ve settled the matter,” and then you have one week break where you don’t have to do any work for this particular case. With a flexible hobby you can pick something that you enjoy immediately rather than have to wait for a scheduled class.

Eugene: Our firm encourages and tries to help us work outside of the office if possible or at home. I’ve only done 2 all-nighters: one was in office and the other was at home. There will be different demands on different files, and sometimes it will be unavoidable that you have to work until you finish a task — I don’t think that any firm doing complex litigation can honestly promise that you will never pull an all-nighter. Back to your earlier question, I personally don’t like the phrase “work-life balance”. I very much prefer to see it as building “a sustainable career”. There will be times when you need to dedicate a little bit more effort to your work and there’ll be times when work will loosen up and you can go and spend time doing other things in your life.

What is important is that you find a place where you are happy, where what you’re doing is not going to inevitably burn you out or cause you to end your career in law prematurely.

J: The next question concerns the associate training program. What sort of training do you conduct for new associates?”

Geraint: I think, on a more structured level, we have crash courses in how to draft well and basic legal thinking, but I think law is a complex job and it’s impossible to learn everything you need to learn to be a good lawyer within six months. We’ve always believed that the best training is experience and guidance, and so we don’t limit the type of work the trainees take on. Rather we see them as just another member of the team, whether this means doing simple research notes or taking on more complex affidavits or submissions. We would match them up to what we think they’re able to accomplish with whatever needs to be done at that point in time.

So that’s experience, and the other part of it is guidance. I think the benefit of working with with us is that our associates place a lot emphasis on teaching and guiding the trainees as they submit each piece of work. For example, the senior associate would give feedback and explain to our trainees how a particular piece of work could be improved, along with how it was well done.

We also don’t shield our trainees from any part of the legal practice. We bring them in for internal discussions and client meetings so that they can appreciate the overall strategy of the file. We don’t just tell them to do a piece of research without any context. We put them on the file and get them involved, to the extent where the moment they are called, they can run the file even when the Senior Associate goes on leave.

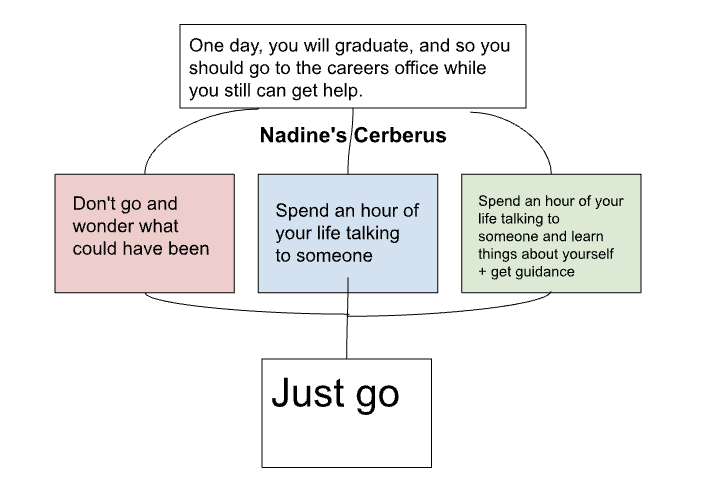

J: Back to a more current context, what do you hope that law students can take away from this fair in general?

Eugene: I think it’s important for them to get the opportunity to speak to people who are already in practice, to understand what actually is involved in each area of practice. For example, if you want to do IP, what actually does that mean? Are you actually doing disputes, are you doing corporate work, are you doing filings? Or if you’re doing dispute resolution: What actually is involved in that?

Law school won’t teach you any of that, you need to speak to people who have done it and then you can better figure out what you really want to do, and then figure out which firm you want to go to, where you can actually learn and be exposed to all these things.

Geraint: Yeah, like I said during our presentation, every firm is different. Students should take advantage of opportunities to speak to lawyers from different firms and really find out what exactly do these firms are like on a day-to-day basis. It’s easy to get stuck on surface labels such as “dispute resolution”, but it’s a lot more complicated than that — dispute resolution can mean queuing up for 2 hours on a Thursday morning for a routine bankruptcy application. Or it could be like Boston Legal where you are in court making impassioned arguments. Some firms do both, some firms do one or another. But it’s a very big difference, and I think that without taking the time to actually ask lawyers about what they actually do, it’s very hard for students to get a sense of what they want to do themselves.

J: You have many subcategories, such as dispute resolution, intellectual property and so on. However, when a law student doesn’t really have a lot of exposure to these sub-categories, or areas of law that he or she may potentially be interested to practice in, how does he or she, without the relevant experience, convince an interviewer that he should be considered for a position in that department?

Geraint: I think that law is a learning process. Nobody knows everything. When I started work I knew absolutely nothing about the foreign exchange market. Within three years, I had to work on a major dispute involving foreign exchange trading. I had to read up on everything, all on my own. The most important criteria is really to just be self-motivated and take the initiative to fill in the gaps in your knowledge.

It’s the same with legal research, once you get the basics down, it becomes pretty straightforward, even if you’re exploring an unfamiliar area of law. You have your textbooks and your cases — Singapore cases are very good at summarizing the law, so the opportunity is always there for you expand your knowledge. But what you really need to show is that you have the soft skills to keep improving yourself.

J: Looking back, do you think you should have done more to gain exposure to more things before working?”

Geraint: Hoestly, I wish I had spent more time in law school doing more non-law work. I think the really big thing that a lot of lawyers should look out for is basic financial literacy: how to read a balance sheet, understanding what’s a current asset or what’s a receivable. Many times in our line of work, we have to review balance sheets, but its not uncommon to find there’s a difference between what the directors say the balance sheet says, and what the balance sheet actually says.

One of the big things that clients also look out for is commercial knowledge. In order to have commercial knowledge, you need to understand a client’s business. What are the latest developments in that industry? What is the general practice? Who are the big players? So, don’t confine yourself to just studying law. Ultimately, the legal industry is a service industry, one that is part of the bigger world at hand. So, without understanding what this bigger world out there is like, you will not be able to become a top-tier lawyer.

Use your time in University to explore: even if your idea of exploring is going on holidays and perhaps talking to a lot of French people about French politics, that is still way better than staying at home and doing nothing.

Eugene: A very practical thing that you can do as a law student is to read every single case and ensure you understand what the case is talking about, not just legally but factually as well. If you are doing a commercial module, the cases there are all going to be commercial cases and will all concern a certain area of business, which does not strictly pertain to law.

When you don’t understand something that you read, go and Google it! If they are talking about some sort of derivative, go find out what a derivative is. If they’re talking about commodities trading, go find out what that is. So that’s a very good starting point if you don’t know where to start. Through all this, you can find out more about this thing we call commerciality.

Geraint: Google and YouTube are your friends. Just because it’s on the Internet doesn’t mean it can’t be helpful.

Eugene: But beware of fake news.

J: Besides financial literacy, are there any other skills that you recommend law students pick up?

Geraint: A very basic thing will be like Excel or Word processing skills. People say they can use Microsoft Word. But how many people actually know how to use Word to its full functionality? These things come across as very minor, but it makes your work a lot more efficient and can mean the difference between going home at 10pm and going home at 7pm, if you really know how to use the tools at your disposal. Excel is magical. Learn how to use it well.

Eugene: Soft skills. Every lawyer will at some point have to bring in clients. You are your own brand. Quite independent of the firm you are part of, you need to convince the client that he should pay for your services. You can’t do that just by being a great lawyer, because that’s a given. What clients care about is: “Do I feel comfortable with this person representing me? When I speak to him, do I feel that he is trustworthy? Is he capable of helping me protect my interests and achieve my objectives?” These are things that are intangible.

Geraint: I would add that you should go out and expand your social network. Don’t just build superficial connections, meet new people and connect with them. You don’t have to meet them every month or so, but just keep in touch. You never know when these people may become CEOs or CFOs of major companies and they may just remember you when they need help. Don’t just see it as purely self-serving: actually be interested in them, find out about them and what they want. Build a proper relationship.

J: Skillswise, do you think you need to be a good mooter in order to be a successful litigator?

Geraint: I certainly think there are overlaps in skills. However, I never did a single moot in law school myself, so I cannot really comment.

Eugene: I did a lot of moots when I was in law school, and I would say it does help a lot as a mooter. It is really the closest thing to practice that you can get to in law school, having to face a set of facts, doing the research, and figuring out how your research ties into your facts.

Geraint: And most importantly, it helps you to deal with the curveball questions that the judges will throw your way in court.

Eugene: But frankly, you won’t get many opportunities to stand up in court and do, basically, a moot. What you will be more involved in in the first three years of practice will be writing, reading, drafting, and research.

Geraint: Even when you do go to court, it’s all very procedural. You have things such as specific discovery where it boils down to how the documents you want are factually relevant and necessary for the case you are trying to run — very few legal arguments are involved, if at all. Or it could be a straightforward application where a creditor cannot pay his debts, and you’re trying to obtain vacant possession of his house – again, very few legal arguments involved.

Even as you spend more years in practice, the chances where you actually get to speak at length about complex legal arguments is a lot rarer than what people think it is. Rather, a lot of it boils down to the story you tell with the facts you have before you.

J: As someone who never really did a lot of moots, how did you, for lack of a better word, qualify to be part of your firm’s litigation department? Exactly what kind of qualities did they look for?

Geraint: My boss has always said that I have a very good commercial sense. Mooting is a hard skill in the sense that it’s very learnable and teachable: you can pick it up along the way. But I would think that my greatest strengths lie in thinking about the strategic direction that a file should take, coming out with ways to improve things, and getting the work product out in an efficient manner. It is very difficult to find a superstar lawyer who is equally good at moots, file management, people skills and networking. People will usually have very varying degrees of strength in different areas and categories. So, you may have very little mooting experience, but you may be very strong in other areas. You, therefore, shouldn’t be discouraged from trying litigation out just because your mooting record is not that great. I mean, it helps, but it’s not the be-all-end-all.

J: A related question would be, how did you showcase your positive qualities to your superiors?

Geraint: Good question. Unfortunately, I’m not quite sure myself. It sort of just happened naturally during the course of my work. You cannot sit back and expect to be noticed, you have to actively put yourself out there in front of the partners. If you think your partner is completely wrong about a point of law, I think it’s your duty as a trainee or associate to say “Hey, I disagree with you”. At the end of the day, yes, your boss does have the final call, but there have been plenty of occasions where we raise an issue to the partners, we debate about it back and forth, and while sometimes the partners may disagree with you at the end of the day, there are just as many moments where they go “I think you have a point, let me rethink this” and in the end they follow through with our advice. So, don’t just sit there and expect to be spoon-fed knowledge.

The advice that you will hear a lot from partners is to put yourselves in the shoes of the person above of you. If you get a piece of work, pretend that you are the person giving out that piece of work, and do it such that if you think that we should be doing tasks XYZ in addition to tasks ABC, suggest that as well.

Eugene: Basically take initiative, and be a lawyer, not just a task-fulfiller.

Geraint: Every law student in NUS can do legal research, but not everybody can be a great lawyer. You have to think about what you can do to set yourself apart from the bare minimum of what everyone else is doing.

J: On that, earlier during the talk, you did mention that a lot of CVs have started to look the same. What do you think would set a good CV apart from one that is not-so-good?

Geraint: I think at the end of the day it all boils down to the cover letter and how you sell yourself. A big part of commercial litigation is telling a story to the clients and the court, and it can be very deceptively simple when we tell a simple story, but at the same time crafting that story can be a lot of hard work.

A lot of these principles can actually be applied to the CV. What are the qualities I want to convey? What is the best way I can convey these qualities? I think when it comes to Singaporeans, with all their Tiger Moms, tuition centres and helicopter parents, everybody graduates with 4 As for their A Levels. Everybody has a perfect score for IB, everybody is the chairman or treasurer of some society, everybody has participated in a moot or negotiation competition, so it’s very hard to be truly outstanding. I think the activities that really stand out are the activities which you basically start on your own accord. If you founded your own charity, like say “Readable”, that is one thing that really stands out because it shows that you have initiative and saw a problem and then took the necessary steps to fix it on your own. Those are really the big ticket items that stand out on your CVs.

Eugene: What Geraint mentioned, “Readable”, is basically a program co-founded by one of our senior associates with his friends outside to help underprivileged children who are falling behind in terms of their literacy catch up. They meet every week to engage in activities such as reading books together and going through English grammar. They were recently featured on Channel NewsAsia as well as in The Straits Times. What does something like that show a potential employer reading your CV? That you’re capable of being passionate about something, and to follow through and build something concrete. I’m not saying that everyone should go start a charity — god forbid! But what do the lines on your CV stand for? Are they there just to showcase a line of empty achievements or to show your employer what skills you have and what kind of a person you are?

J: The final question would be what advice would you have for current law students, and in particular, the first years?

Geraint: Be flexible and keep your options open. The world is changing: what may be a lucrative career in law today may not be so lucrative anymore in the future, and vice versa. Remember to keep your ear to the ground, look out for new opportunities, and don’t close your doors too early. This applies not just to the first years but all through practice. Have a plan, but don’t be afraid to change your plan if the need arises.