We met Professor Chen-Wishart at the lobby of the Eu Tong Sen building. There, she is seated comfortably on one of the lounge chairs, with her backpack and laptop seated on either side of her. We say hello, she says hello — and is very nice (even though we’re kinda late) — and we start the interview. It is her last week in Singapore, and she will be delivering her last lecture for the year on the upcoming Thursday. We’d figured it’d be good to get to know Professor Chen-Wishart before her departure.

“Outside of academia, outside of school, what do you do in your free time?”

“Well, my kids have grown up, you know, so we usually travel a lot” says Professor Chen-Wishart, an unsurprising answer from (what we’ve gathered) a fairly international woman. “My kids are the most important things in the world to me, so I love spending time with them. I do scuba diving, a lot of things that a middle aged woman probably shouldn’t do, but I do, because of my kids, like going in a jeep with a crazy driver up to a volcano, and that sort of thing.” “I just took my son to Indonesia, and we did a lot of ‘teenage-boy things’ ‘cos he’s a teenage boy, and I’m an old mother with a teenage boy, so I get to do an odd mixture of law and teenage boy activities, and I love doing that.”

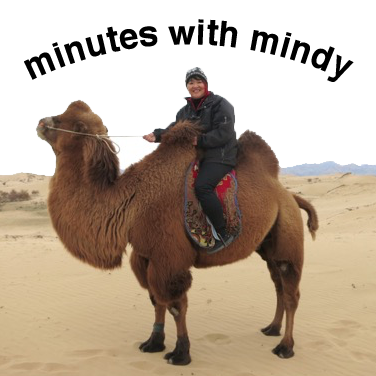

“Oh,” Professor Chen-Wishart seems to interrupts herself. “I brought them to Iceland! With Terry Kaan and Michael Hor who used to teach at NUS. They’re good friends of mine.” She then offers to send us a picture of her, riding a camel, on the trip.

Prof Chen-Wishart, with Michael Hor and Terry Kaan, as promised.

Other than travelling, Professor Chen-Wishart listens to audiobooks (currently, a non-fiction book called Sapiens) and adds on that she loves law so much now, that her work is basically pleasure for her. Her favourite part of it? “Meeting new and different students and law academics, other than those in Oxford.” She has taught all over — Singapore, Hong Kong, Germany, Taiwan, New Zealand, and so on, and she often brings her sons.

Having travelled so much, we were of course curious to know: “Is there any particular reason why you like coming back to Singapore?”

“Well, I think it’s because I was born in Taiwan, and I immigrated twice, involuntarily.” First to New Zealand, she says, and the second time, to somewhere else, and that it’s it’s too long of a story to explain. In total, she holds three passports — UK, Taiwan, and New Zealand. “Once you reach middle age, you always want to go home.”

“My Chinese is not good enough to go back to Taiwan to teach, and while I love spending time in Asia, I don’t just want to be a tourist. So I love fact that I can come here and do what I love doing, teaching, eating good food, and spending time with people who look more like me.” Thereafter, Professor Chen-Wishart explains that she still very much still practices filial piety, and her 6 weeks in Singapore also mean spending at least 3 weeks with her parents, who just love Singapore!

“I’ve just grown to really appreciate Singapore. And the students are good, I have to say. The students are clever, they work hard. The only problem is a few come in late and some talk.”

“I remember when you sent out the people from our year, last year.”

“I very rarely do that! Sometimes I’m called the oriental dragon in Oxford.” (She is not wrong. This is one of her many nicknames in Oxford.) “I think it’s better for you, if we make things clear – you don’t have to come, but if you do come, then you listen. Right? Otherwise, very bad for my self-esteem.”

We wonder how this philosophy came about, and we’re also interested in her background, so we ask: “If you could go back in time and tell yourself one thing or give yourself advice what would you say?”

As a result of her international background, or a “citizen of the world”, Professor Chen-Wishart is, today, a clear fusion of Traditional Chinese and Western values. “I’m really lucky to be East and West; new world and old world.” But as she speaks, we realise that she came from a typical Chinese family.

In giving advice to her younger self, she references her Chinese roots. “I think as a Chinese person I was brought up to be very hard on myself — sometimes we are our worst friends. But you have to be your own best friend, especially when you’re feeling down or insecure or think you’re not very good. I went through phases where I would think that, “Oh, I’m terrible, I’m not very good,” but well, if you were your own best friend you wouldn’t say “yes, you are!”. You would say “Don’t be silly! You’ve done the work. You’ll be fine.”

“So I think it’s about being kind to yourself, and being kind to other people.”

“Firstly, be nice to yourself. Secondly, find your passion. It can be anything, but once you learn what you’re passionate about then you will learn how to learn. If you learn how to learn, you can learn anything.”

“How early did you know your passion was going to be law?”

“Well,” Professor Chen-Wishart chuckles. “My dad kept telling me that I was arguing with him.” Laughing, she imitates her father: “I send you to school, and university, and you’re arguing with me!”

Professor Chen-Wishart’s passion for the law is striking, but even for someone like her, finding her passion wasn’t that straightforward. “I, well, did Pre-Med, like all good Chinese students did, and I did a Masters degree in History.” She mentions that it was only later that she realised that law, for her, was the easiest thing. “I love to know how you resolve conflicts. I love to explore how one tries to come up with principles to navigate conflicts to achieve the best outcomes for individuals and for society. I love to see how the law mediates, because people get into conflicts all the time — small conflicts, big conflicts. It’s very fun.” It’s inspiring to hear this, and we can only hope to find something which piques our interest as much as this.

“I like to see how law expresses all the things that human beings are. It’s really important to see the law as something to solve human problems, rather than just some system of logic. Every subject of private law is always about how much freedom one has, and how much one has to be concerned with other people.”

What boggles the minds of many Year 1s is what makes Professor Chen-Wishart tick. “I like Contract and all its many forms because Contract, to me, talks about how you should relate to your fellow human beings, yeah? And that is the tension between autonomy and fairness; that’s a tension that we all live with every day. It’s how much we can be selfish, how much we can, or need, to be self-regarding and how much we need to be others-regarding.”

Seeing it this way, we guess Contract does seem a little sweeter.

“Law is the best subject in the world,” Professor Chen-Wishart very confidently proclaims, while our souls leave our bodies. “You do everything — philosophy, history, linguistics. And I’m so glad I’m not a doctor because I don’t want to look at people’s bits all the time”

“Have your conflict resolution skills helped you with your children?”

“Well I suppose in many ways I have learnt. When they were little, and you wanted them to brush your teeth you could say, “Do you want to go brush your teeth or do you want to go to bed early tomorrow?” She laughs fondly at this. “You always give them a choice. I have three very different children, so they require very different conflict resolution techniques, and you learn them.”

When asked if any of her children would study law, she shakes her head, saying, “No, no, no, none of them would go near law!” Her three children are spread out in vastly different fields — one is an artist, who illustrated the cover of her textbook, another is doing a PhD in nutrino physics, and the youngest has just finished his GCSEs.

“One never respects one’s mother as much as one respects other people. I think it was only when my eldest son realised that his cool friends were reading my textbook that he thought I was somebody.” Laughing, Professor Chen-Wishart imitates her son: “You don’t know anything mum, and you’re so not cool!”

“We always wondered — why do you dye your hair? It’s something we all notice, because it’s not very common in the faculty.”

When Professor Chen-Wishart was here last year, her fringe was tinted red. Now, it is a darker, less obvious purple. Her hairstyle is cool for someone of her age, and she knows it — when we ask her why her hair’s always changing, and she tells us the story of how it all started.

She was in Taiwan, she said, on New Year’s Eve. Instead of a New Year resolution, she decided on a new hair cut. She had long hair then; she told the hairdresser to do anything she wanted. Snip, snip, and a quick dye later, she’s got a spanking new haircut. “I was in shock at first, but I got used to it, and now I quite like it.” She mentions also that a motivating factor of dying her hair was to deter her sons from doing the same — they did stop once she got hers done, because “it was just not cool, you see, once your mother does it.”

“Did that really work?”

“The minute I did it, they stopped. It was absolutely no longer cool. They thought it was the most uncool thing.” She says, gesturing to her hair. “They have beautiful plain brown hair now. It worked pretty well. I’m hoping they won’t push me to piercings or tattoos.”

It’s clear throughout the interview, and even in her lectures, that Professor Chen-Wishart’s children mean the world to her. We can’t help but outwardly wonder if her “oriental dragon” behaviour extends to her children. Very quickly, she steps in to clear that up.

“Oh no, no, one’s always a victim of one’s children. An Oxford student once declared — no one gets one by Mindy except for her kids — and that’s true. I think with great love comes great vulnerability — the more you love the more vulnerable you are, and so to have kids is to become incredibly vulnerable.”

Before we leave for good, we ask our customary closing question: “Do you have any advice for the students?”

“My advice would be my favourite fairy tale, about the Emperor’s New Clothes.” For those not familiar with it, the Emperor is given this amazing outfit, made from special fabric, and is told that this outfit would be invisible to anyone who isn’t clever. “The truth was that there was simply no such clothing, and he was, in fact, entirely naked. All of his courtiers and officers were too scared to appear stupid, so they kept praising the non-existent cloak … and, it took a child to say “BUT THE KING IS NAKED!”

So, I think that law students need to be like the child in that story, because while you are often told the distinction is between yes and no, this and that, you don’t always see it. Sometimes, it doesn’t quite make sense to you. You should be like the child in The Emperor’s New Clothes — you should say “I don’t see it, the distinction seems naked”.”

“You should ask questions, you should tell it as it is, and you should always, always have insatiable curiosity.”

When the interview is over, we ask Professor Chen-Wishart for a photograph. Outside Block B, we ask if she could sit at the wooden tables for her portrait, and she almost immediately sits on top of the tables, and not on the benches.

Maybe she’s picked up some spunk from her sons.