Hey guys! You might be surprised to see me again, since the post about exercises for legal success was supposed to be my last. However, I was returning a library book and discovered that I could borrow books until Commencement, which suggests that I get to enjoy all of the other privileged that I enjoyed as an NUS student until then – including the abus- use of this student magazine! Anyway, back when I was in Years 1-2, my main schtick in NUS Justified was my illustrated articles (of which only two have been published) and I figure that a series of drawing “tutorials” (in the barest sense) should make for a suitable swansong. As the title implies, this series won’t get you an exhibition at the National Gallery – they’re meant for complete beginners who want to draw something that vaguely looks like the real thing. If you can already draw decently well or want to produce something that you’d dare to post on Instagram, this post isn’t for you. Without further ado, let’s begin the first instalment of this series by learning how to draw our favorite furry friends who hang out at the Lower Quadrant! (I refer, of course, to the cats and a boy with exceptionally hairy legs who hangs out at the Angsana Room).

Supplies

Let’s begin with our supplies. You’ll need (1) something to draw with and (2) something to draw on. Since this is a very basic post, any pen or pencil that can produce a clear mark on a flat surface will do, although I’ll explain some basic effects that you can achieve depending on what you’re using.

Similarly, any paper should do – even recycled printer paper. That said, if you want to be fancy, you can shell out a little more for nicer drawing paper like this. You can get them in lots of different sizes – a small size will suffice because I’ve got lousy spatial awareness so I can’t draw anything too large, although a large sheet can be used for many small doodles. They also come with different roughness – I personally like rougher paper that offers some resistance to my pen/pencil and I find that it helps me get different textures.

If you really want to save paper, you can use a whiteboard and marker, or install a drawing app on a tablet. ProCreate works well on iPad, if you’ve got $15 and an old tablet lying around, and a cheap stylus can go for around $15 too. Personally, I’ve never gotten the hang of digital drawing but maybe you’ll have more luck.

Anatomy

When drawing figures of any kind, it’s a good idea to learn a little bit about its anatomy. You’re not aiming to be a veterinarian or a full-time caretaker – just figure out where the shape is supposed to bend and curve.

a) Skeleton

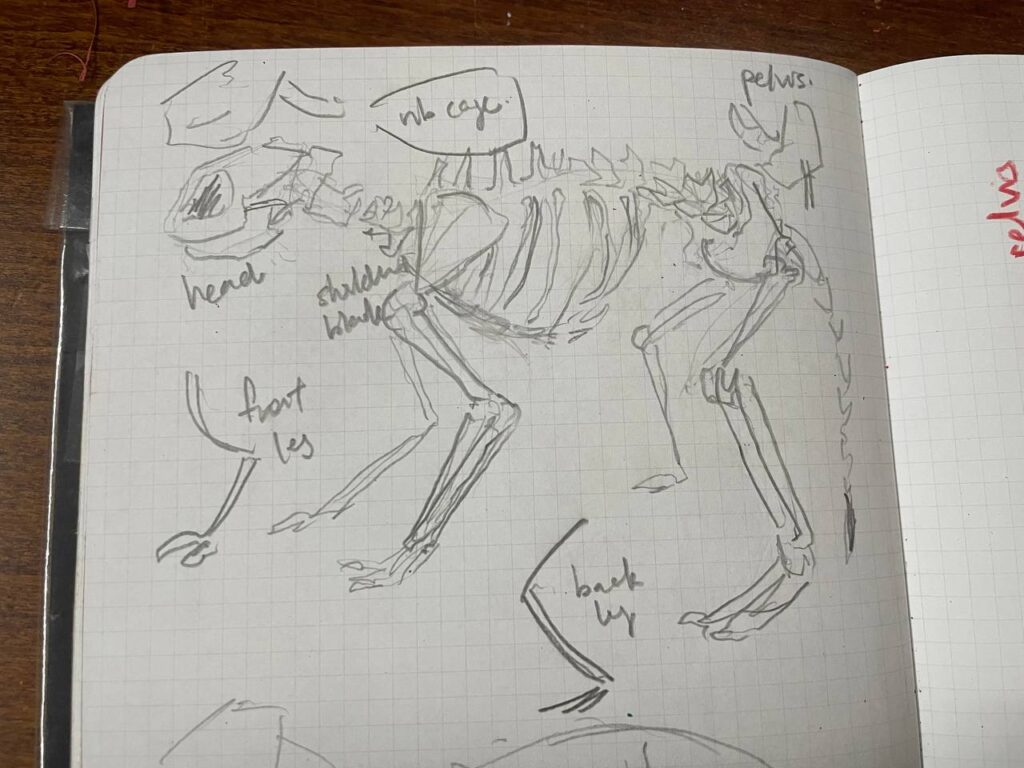

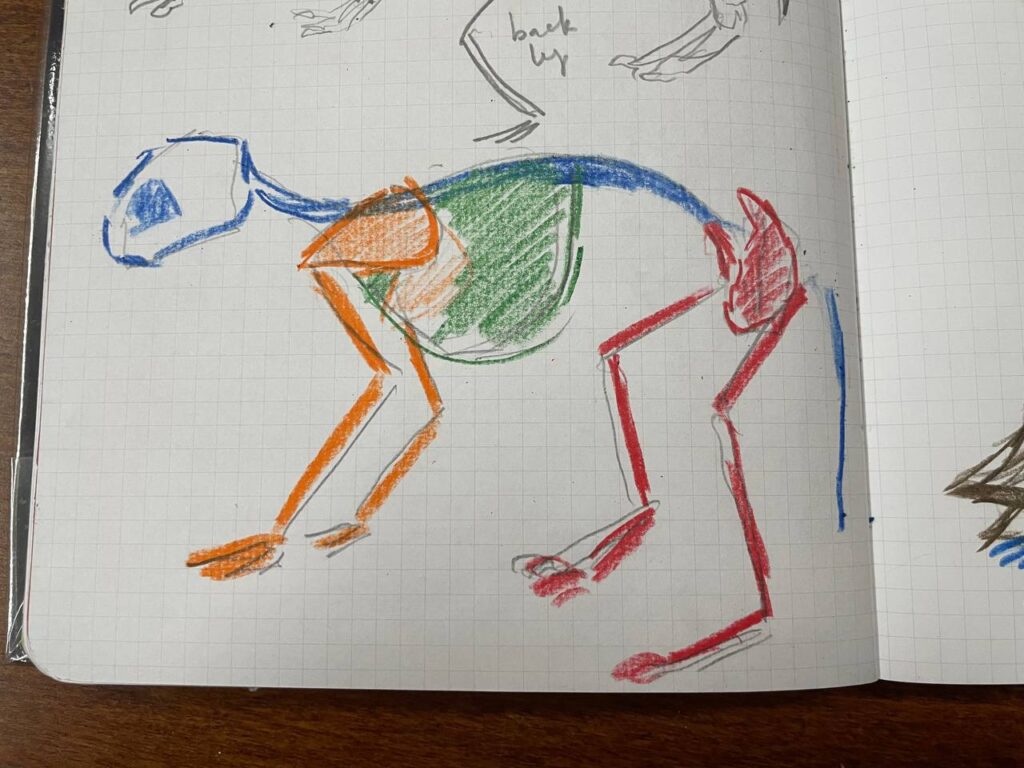

You may have heard of the method where you use sausages and eggs to represent the figure’s body parts but I don’t think that’s very helpful for cats. Although cats and humans both have four limbs, a head and a torso, cats are bendy and stretchy so their bodies don’t always follow the same configuration of sausages and eggs like a human’s limbs do. Hence, we’ll use the skeleton as a guide.

To help you out, I’ve taken the initiative of skinning this cat that my friend has kindly donated to the further the arts.

It’s a bit too complicated to reproduce every time you want to draw a cat so I’ve simplified it.

Make a note of the direction in which the cat’s joints bend so you don’t draw one that needs a wheelchair, and the general proportion of the limbs so you don’t draw an alien.

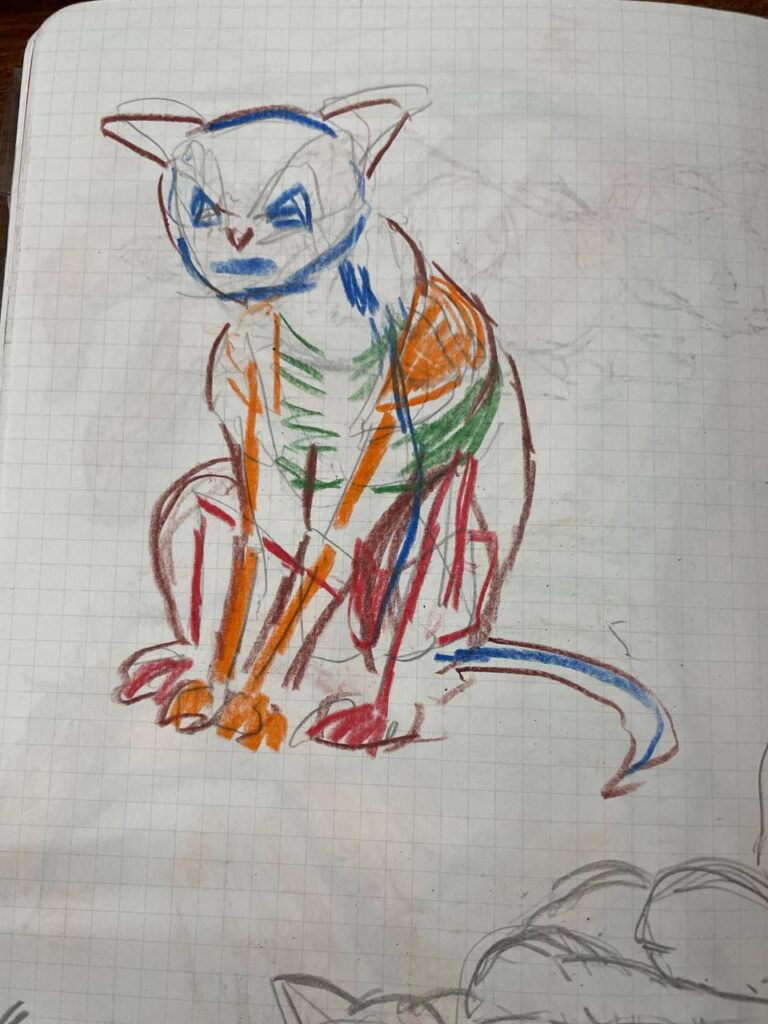

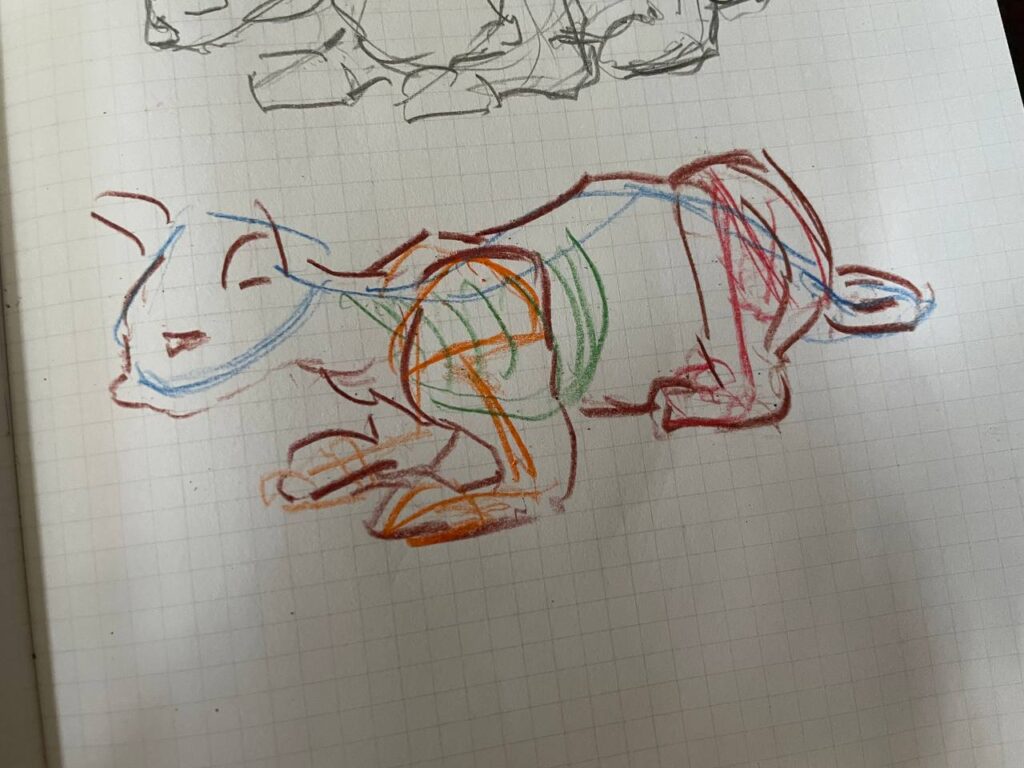

b) Muscles

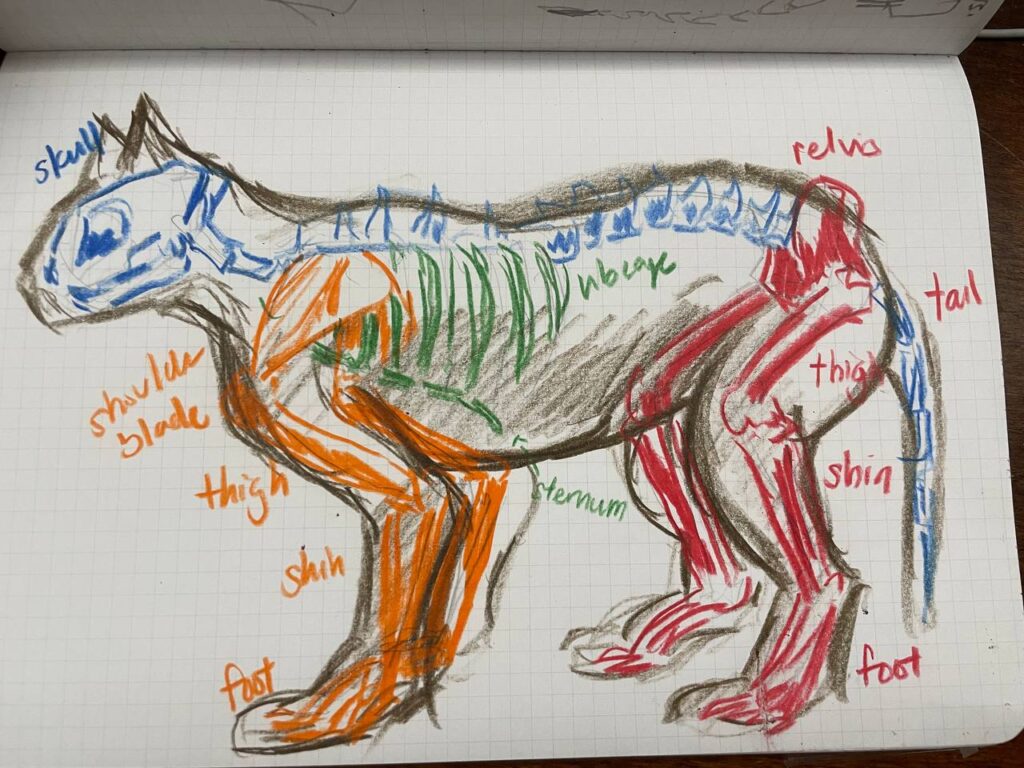

As for how the muscles fit onto the skeleton, I don’t like uses eggs and sausages because cats are more flexible and floppier than humans so the fleshy masses like their bellies may lengthen when they hang down or envelop nearby limbs like their thighs.

If you’re drawing from a real-life example e.g., a photograph or an actual cat, it’ll be easier since you’ve got a real example to see how the flesh changes depending on posture. I recommend using photographs until you’re comfortable with drawing them quickly, then you can progress to drawing real cats before you. After that, once you’ve drawn many cats in many different positions, you’ll be able to imagine what the cats should look like.

Here are some general tips:

- Just like how maritime delimitation follows the general direction of the coastline, the cat’s musculature shouldn’t noticeably deviate from the skeleton.

- Unless you’re drawing a large cat (e.g., cougar, jaguar, lion), the musculature won’t be too exaggerated. Imagine how you might draw a very muscular character with defined muscles and a taut figure; then compare that to how you’d draw a chubbier character using large blobby shapes (ovals and circles). A cat should be somewhere in between: use blobby shapes around the bones, then tighten it up to make the figure more elegant and streamlined.

- Cats are generally quite cute. If the cat looks too angular or strange even if you follow the skeleton and you’re confident that you’ve got the bone proportions correct, feel free to adjust the drawing to make it more pleasing to your eye. Chances are, the angle of the cat might mean that the bones aren’t arranged in the way that you think, and your gut instinct might lead you towards a more aesthetic and accurate figure.

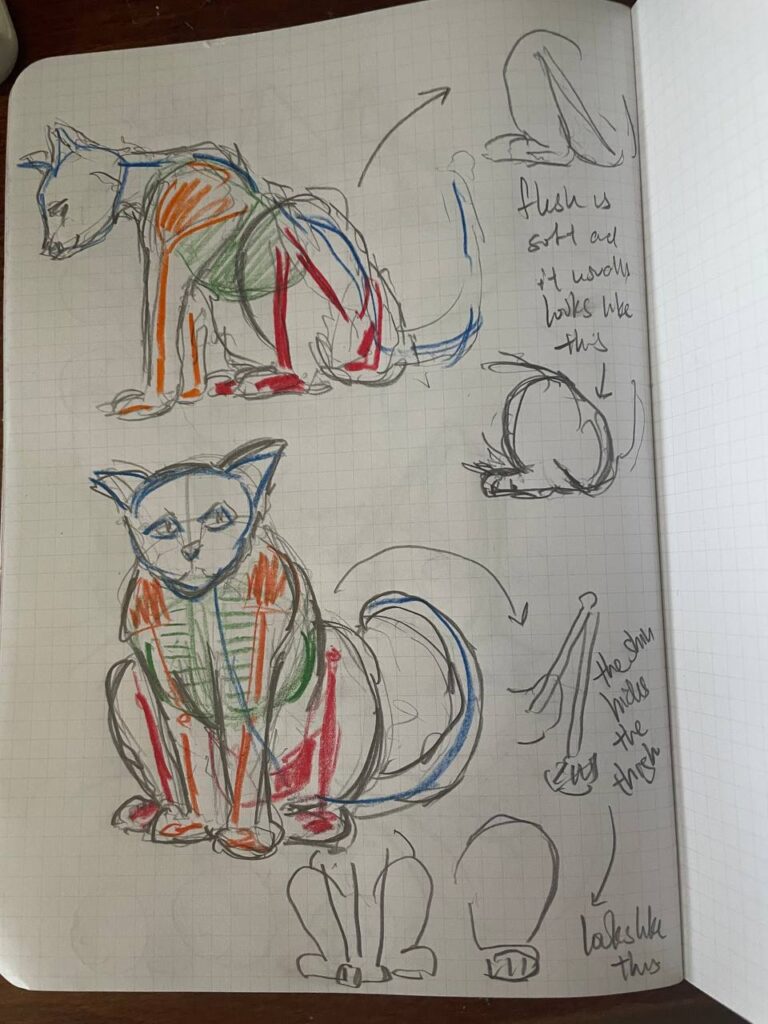

c) Head

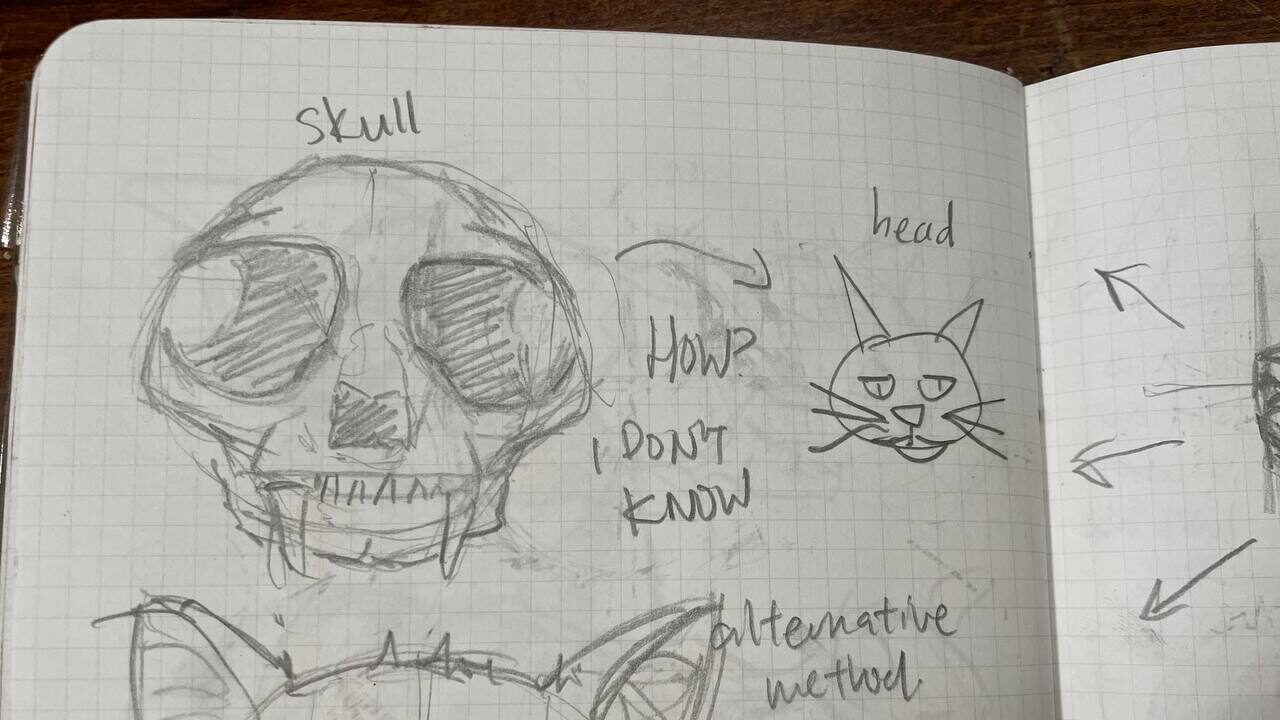

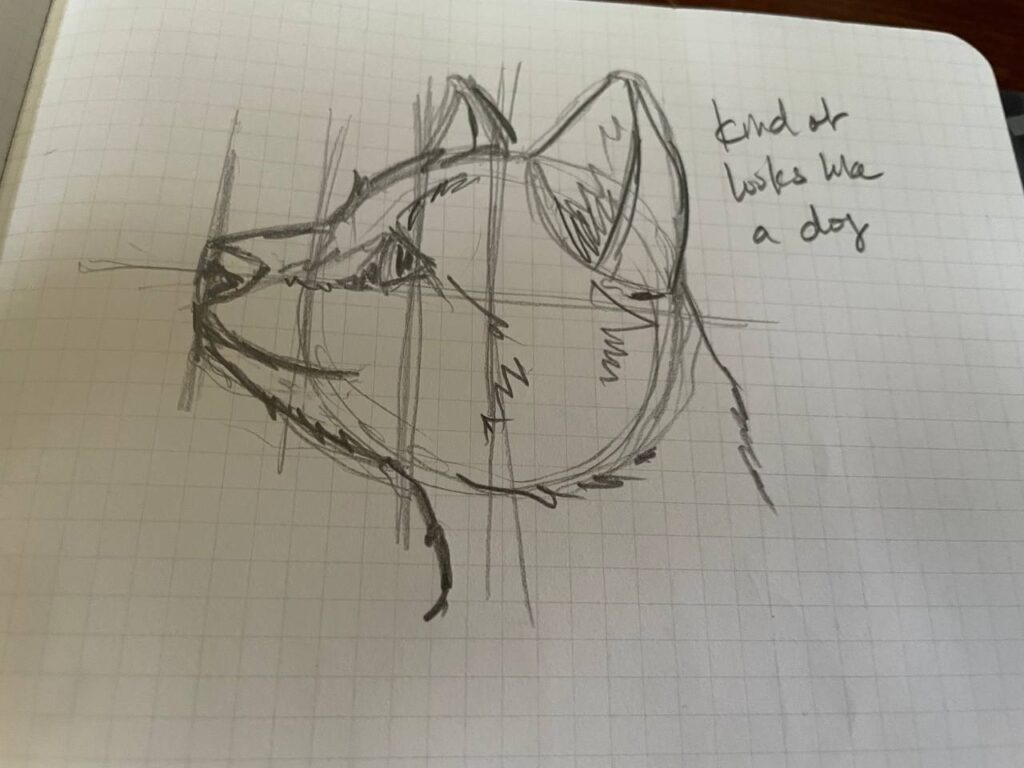

When drawing fanart, it’s more fun to focus on drawing their heads and faces, for obvious reasons. That probably applies to cats – a headless cat is much less pet-able and cuddly – so I’ve included a section focusing on the cat’s head. When drawing human figures, I’d recommend learning how to draw a skull and facial muscles to facilitate drawing different facial expressions, since you’ve got to know which parts of the face can open, shut or clench up. However, I’m unfamiliar with the facial expressions of our feline friends (which might explain why they keep biting me) so I’ve never got the hang of converting the underlying anatomy into a nice-looking face.

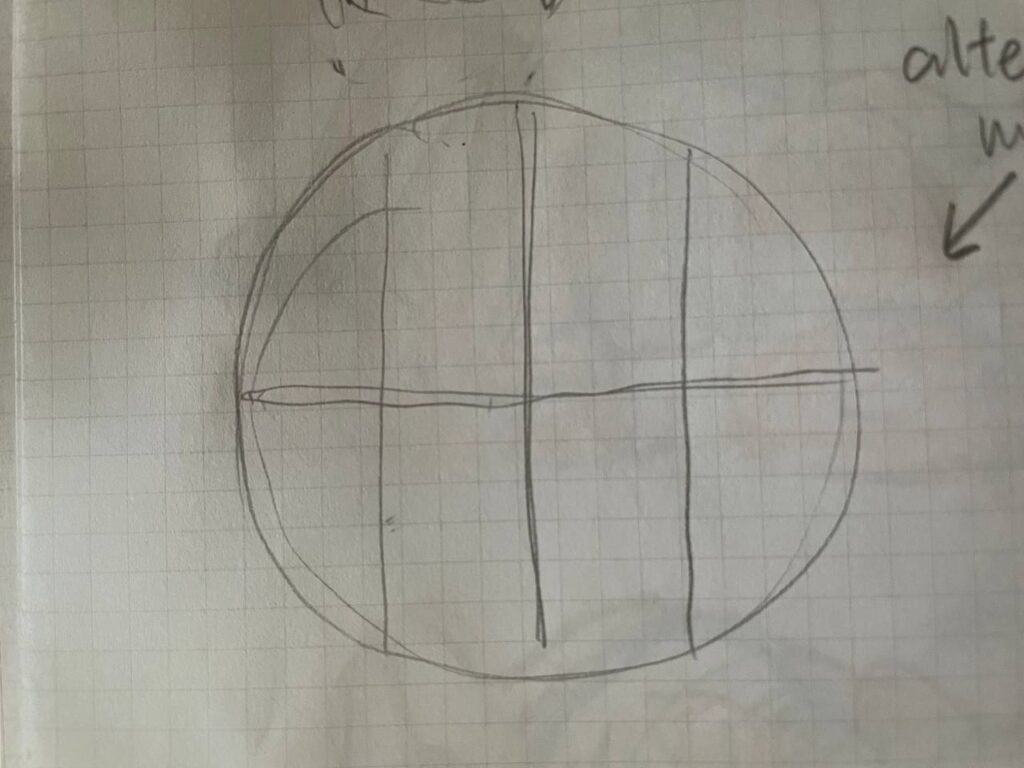

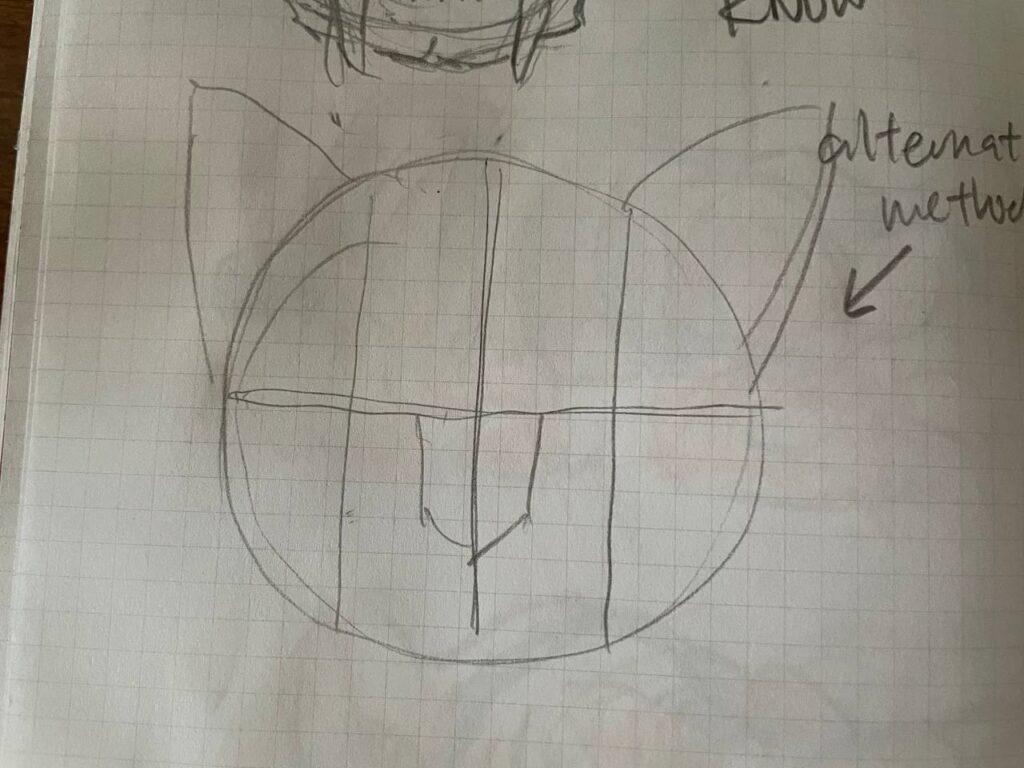

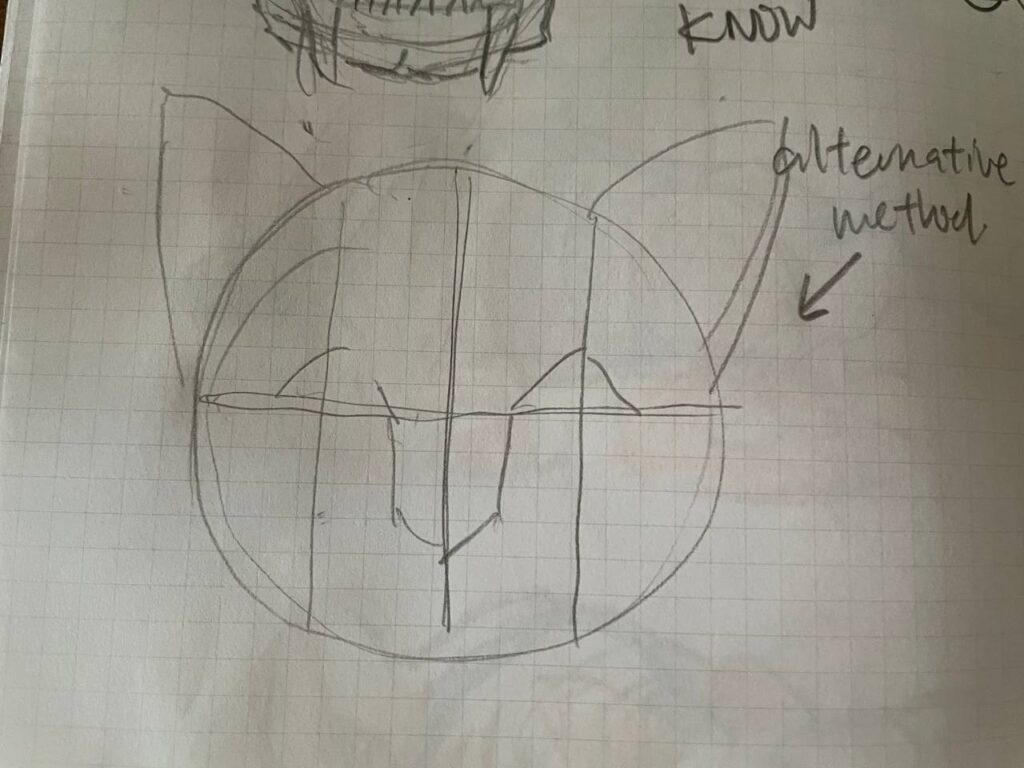

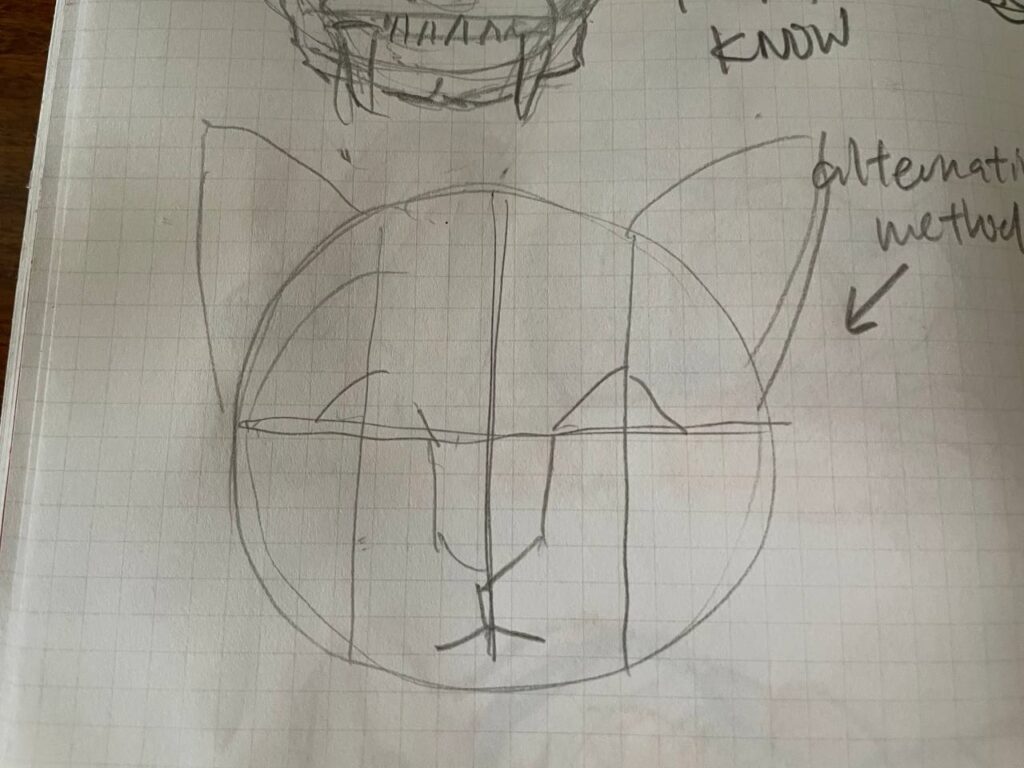

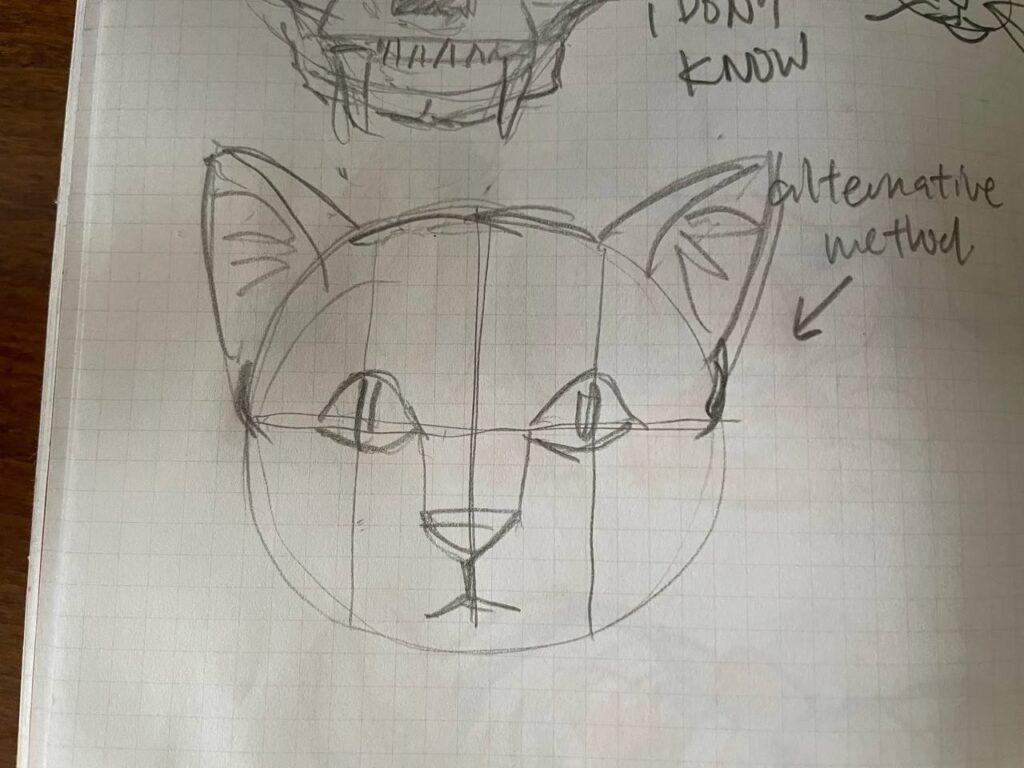

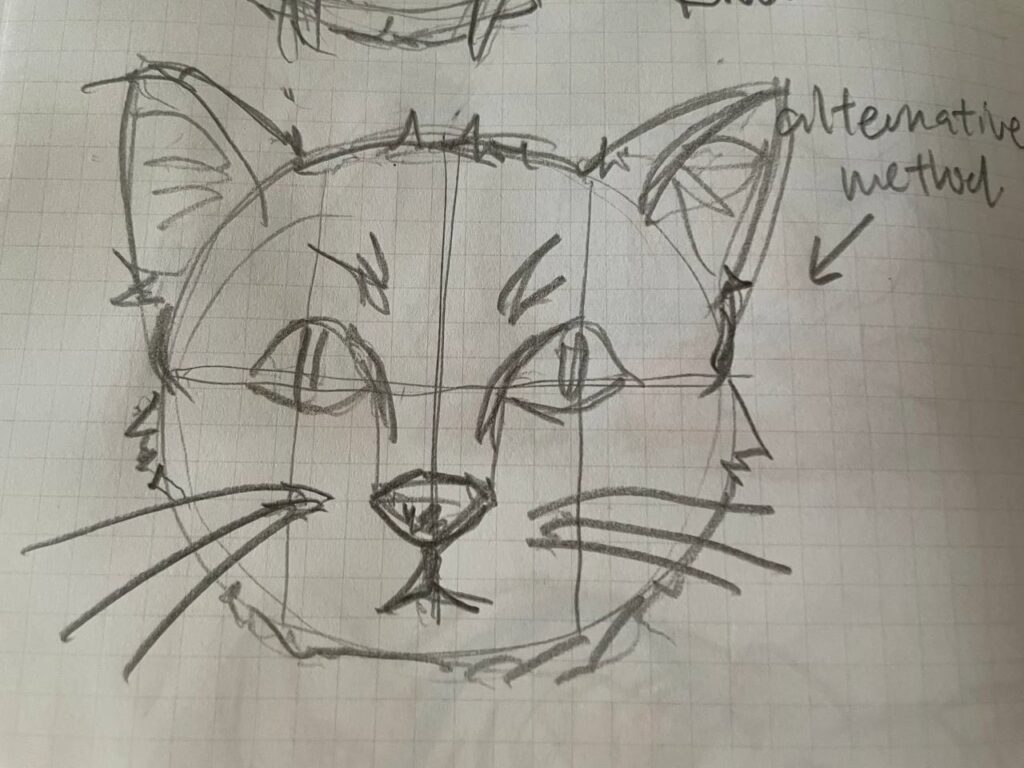

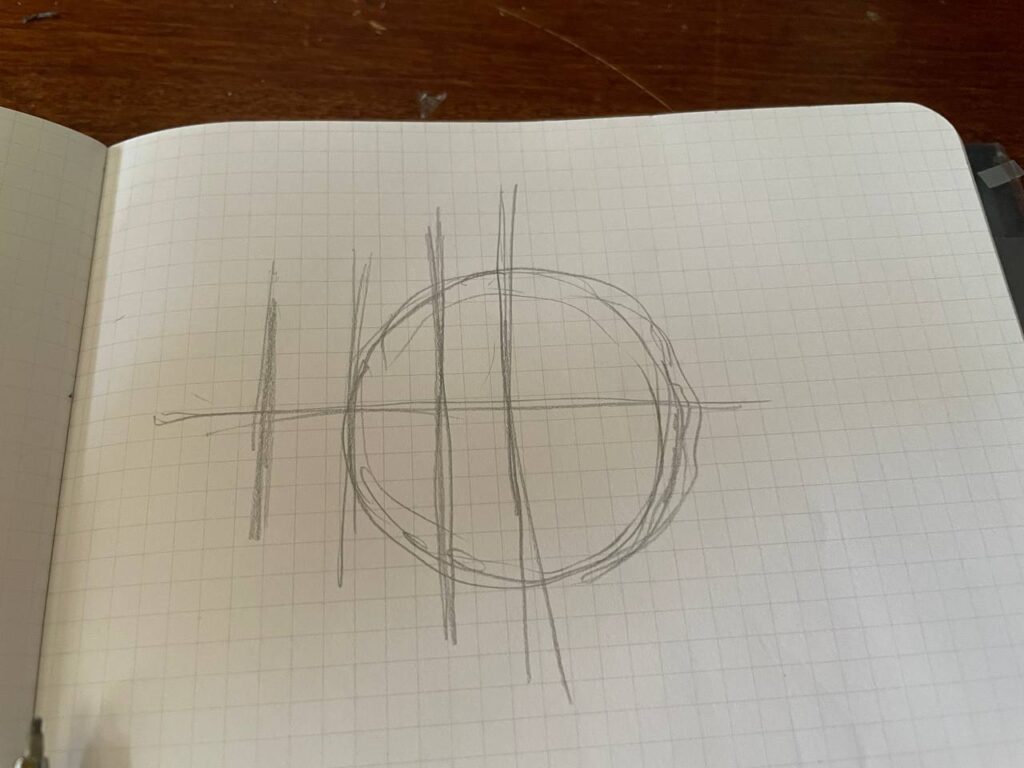

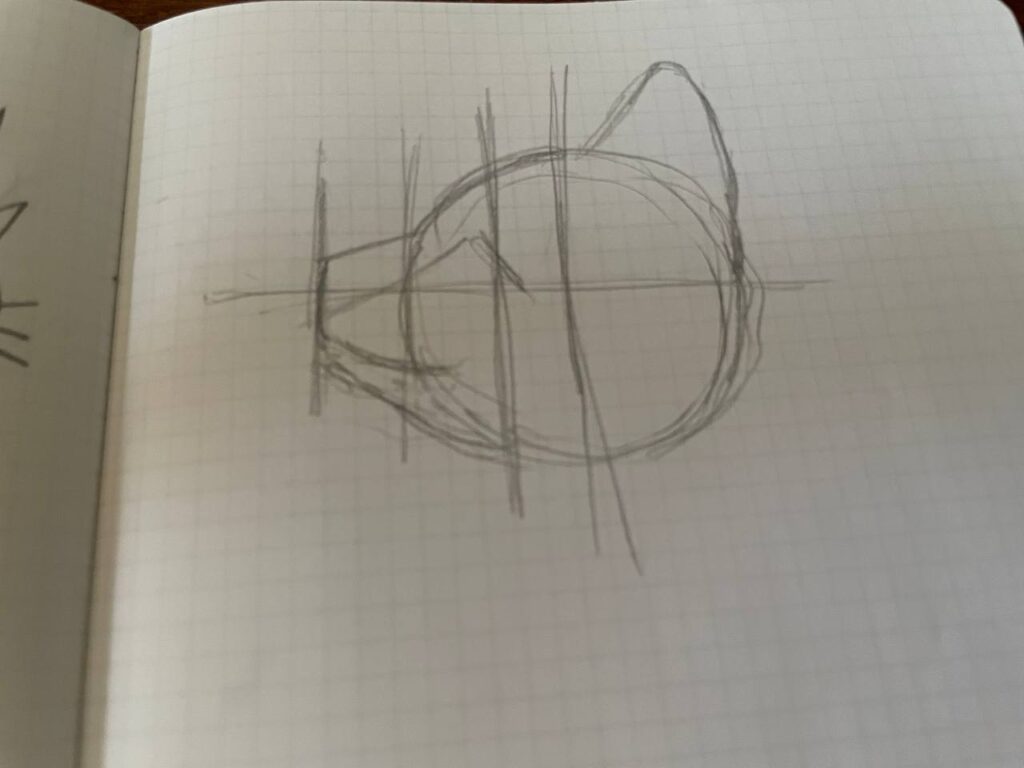

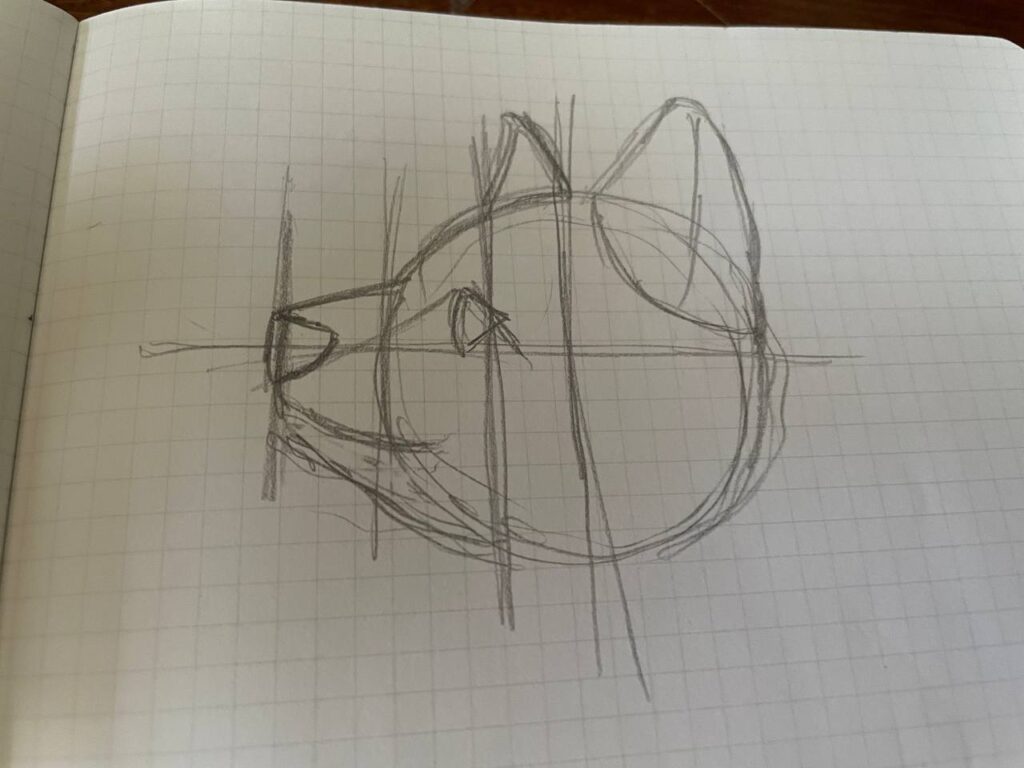

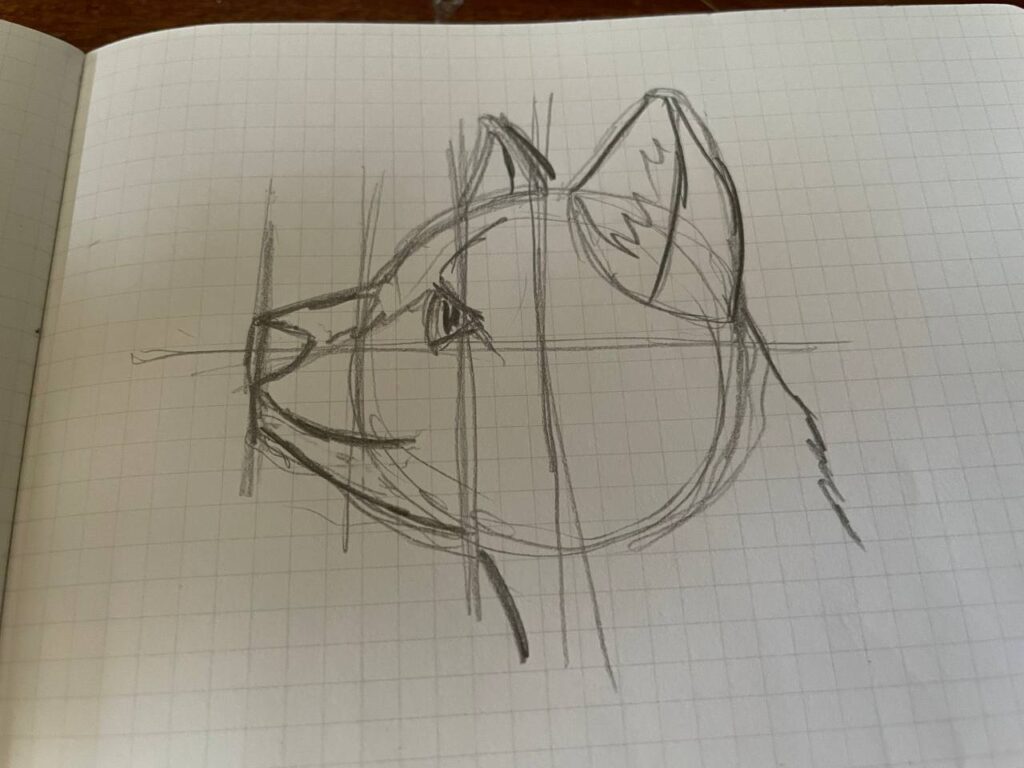

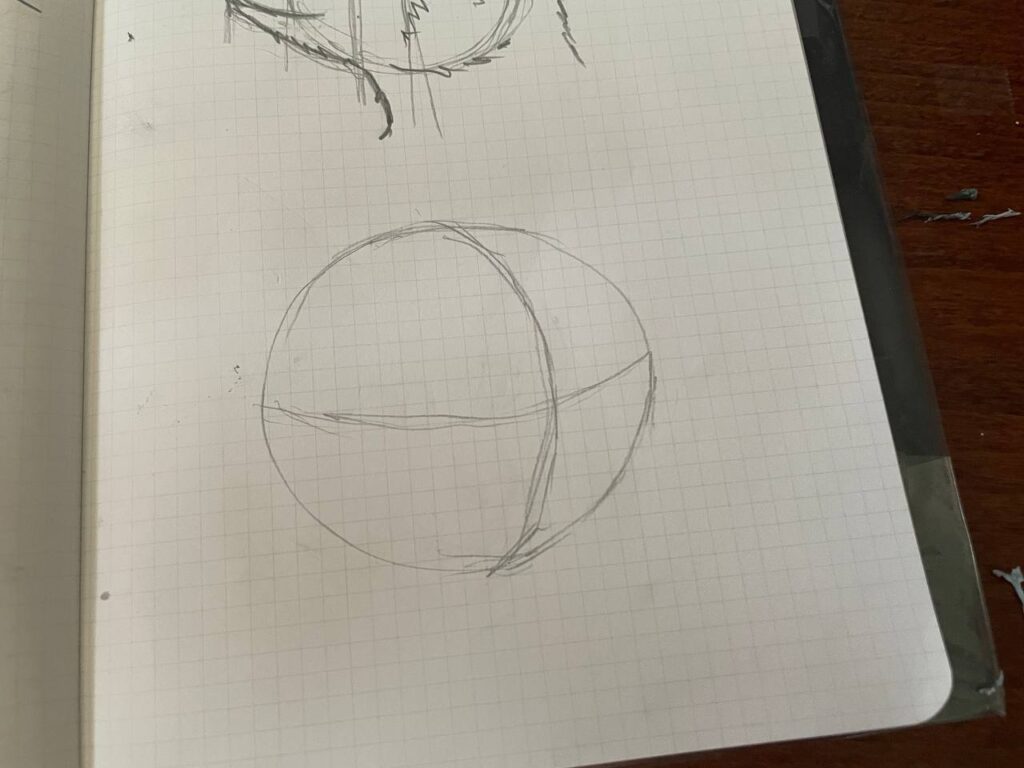

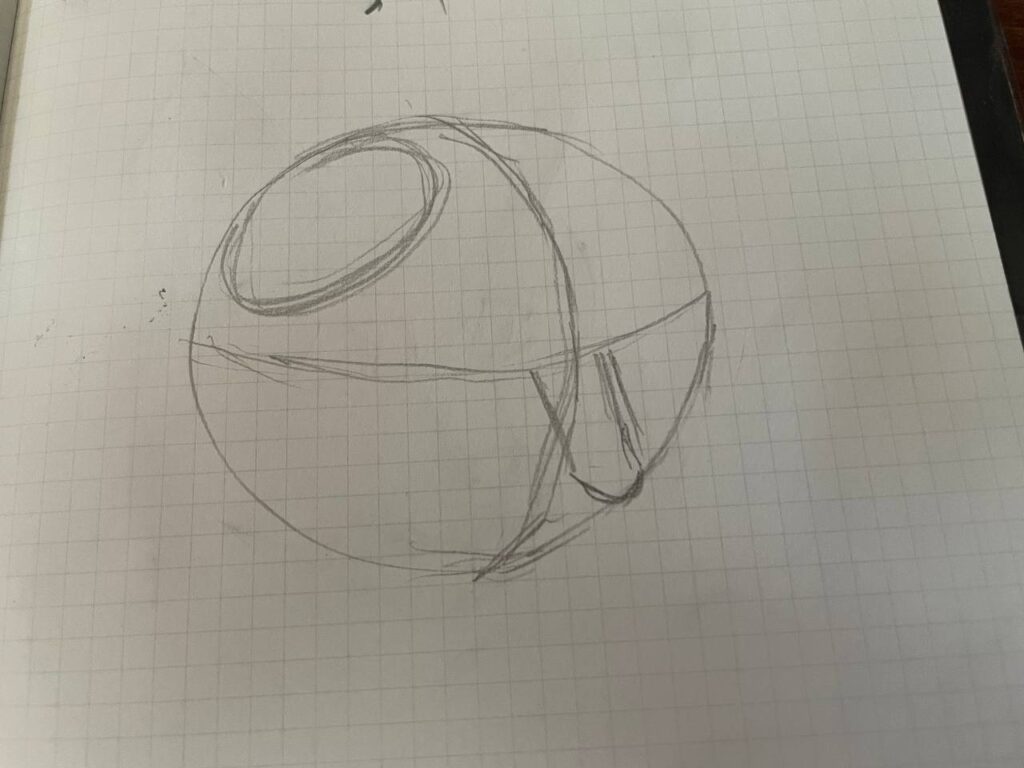

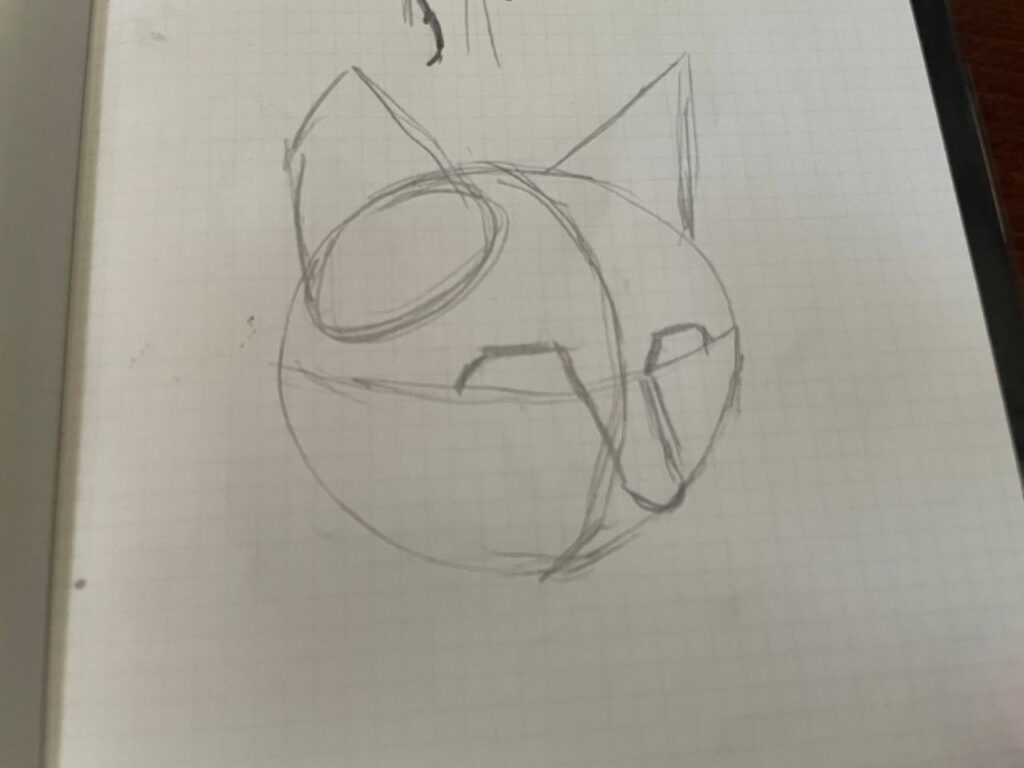

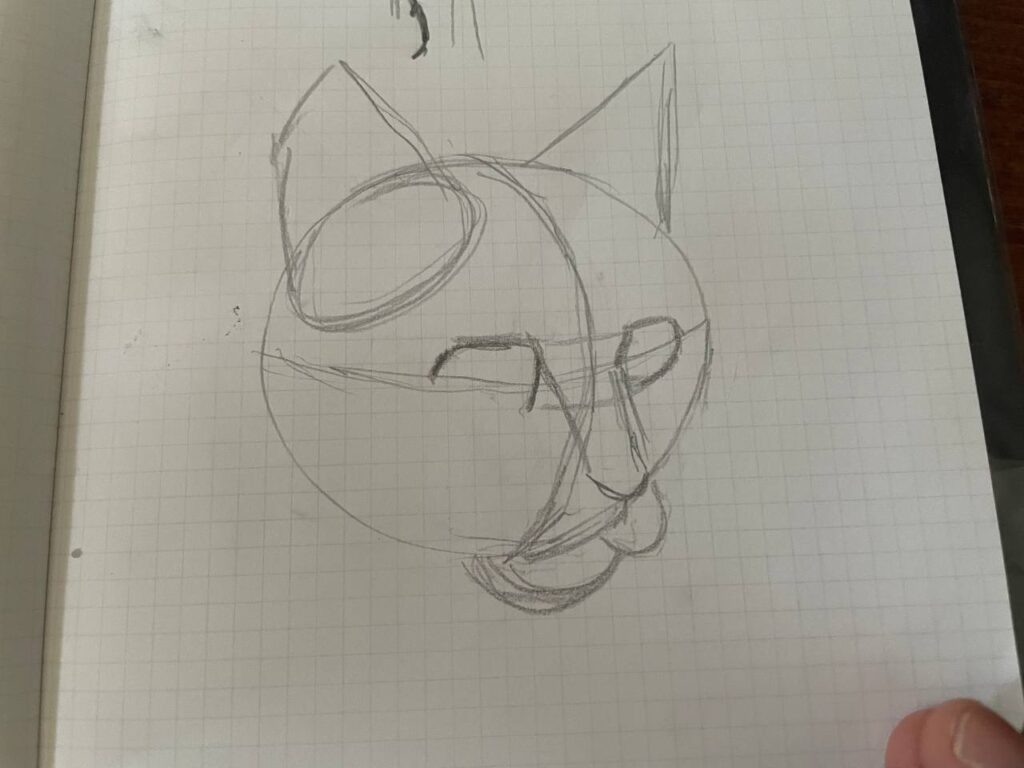

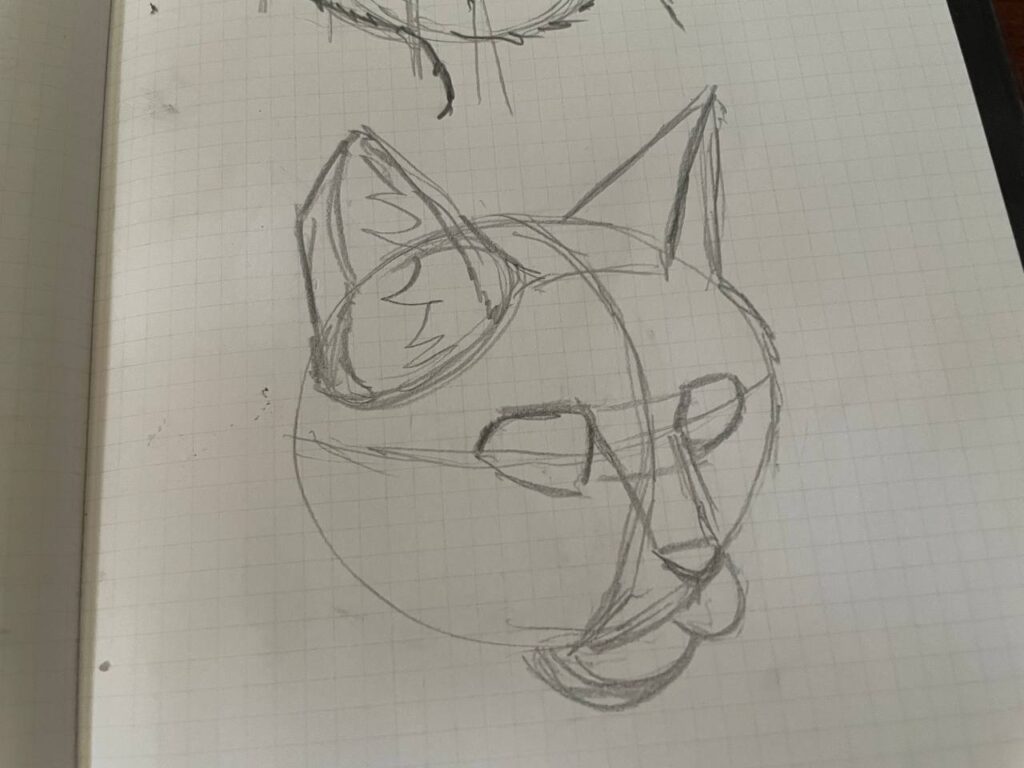

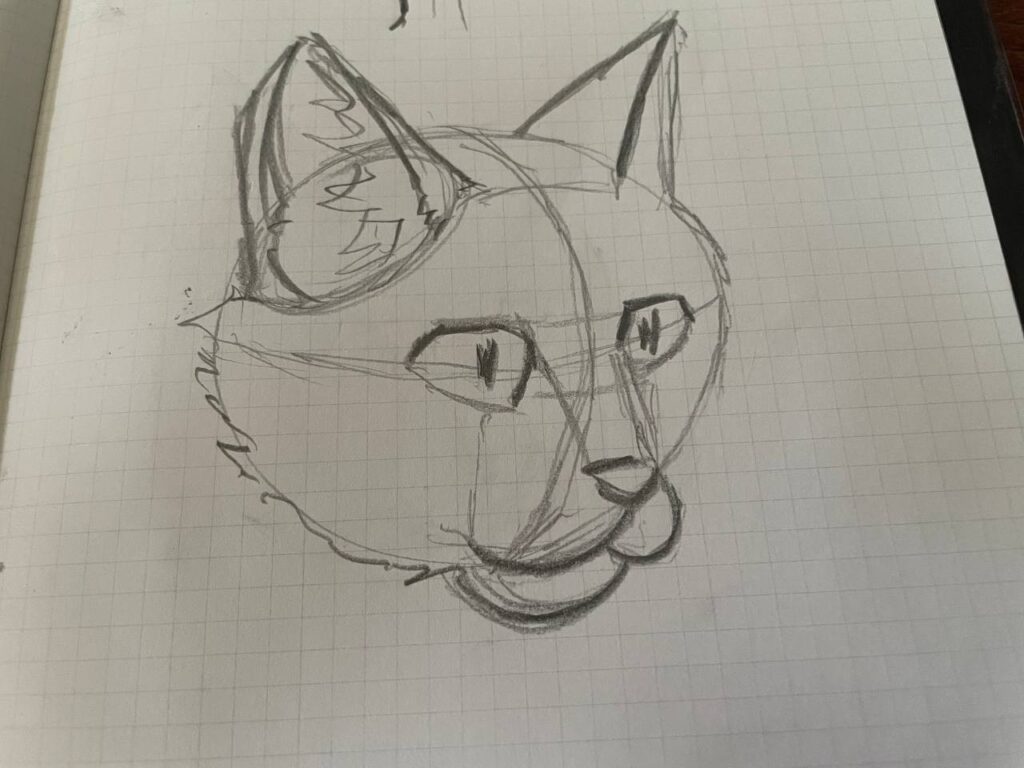

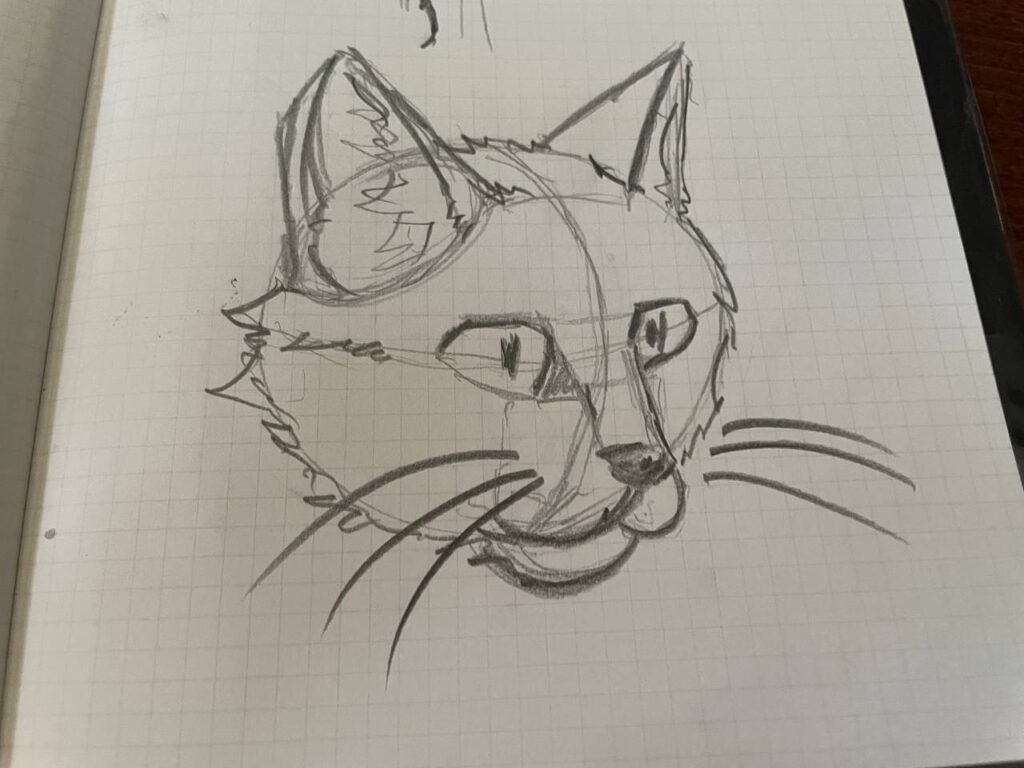

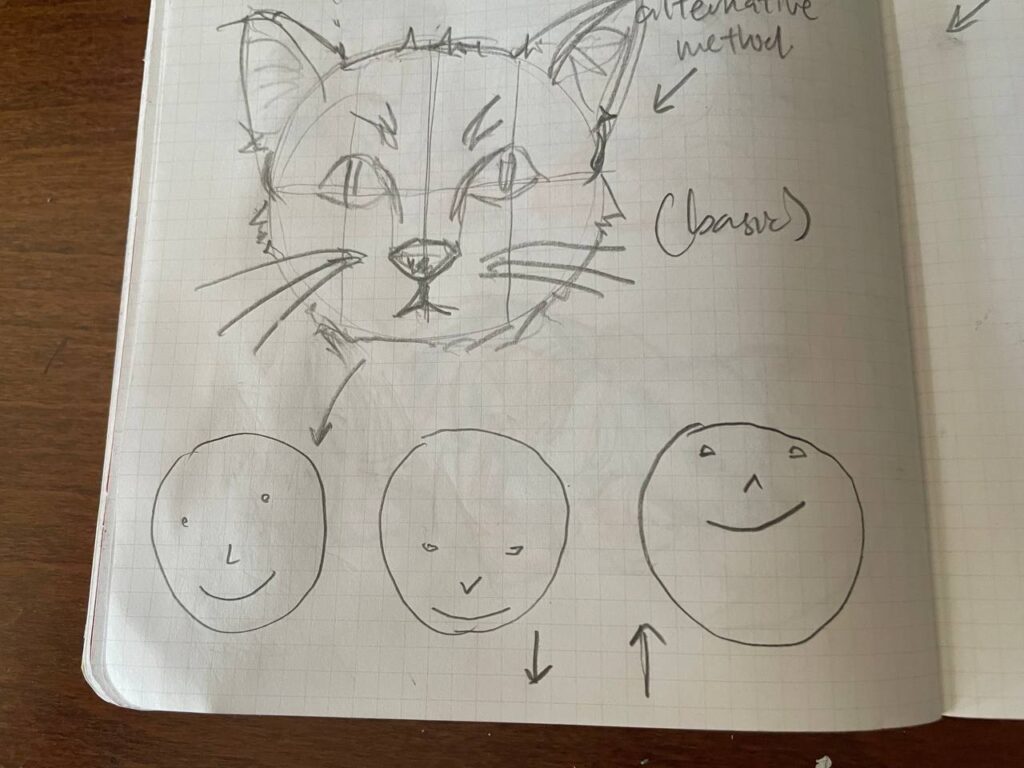

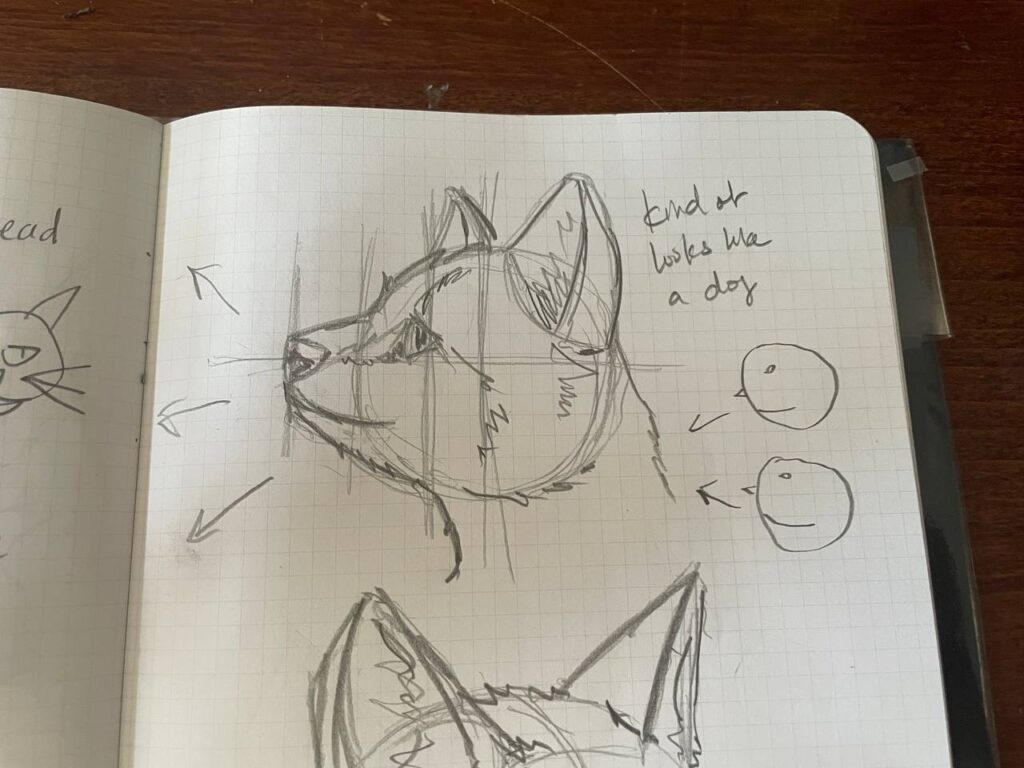

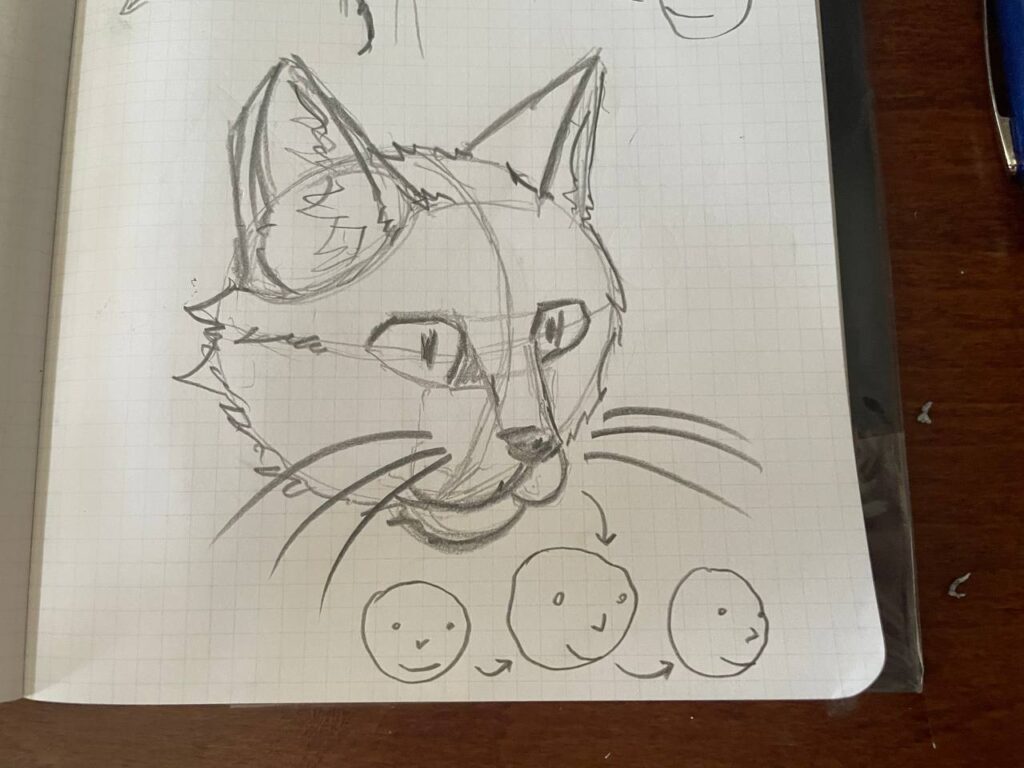

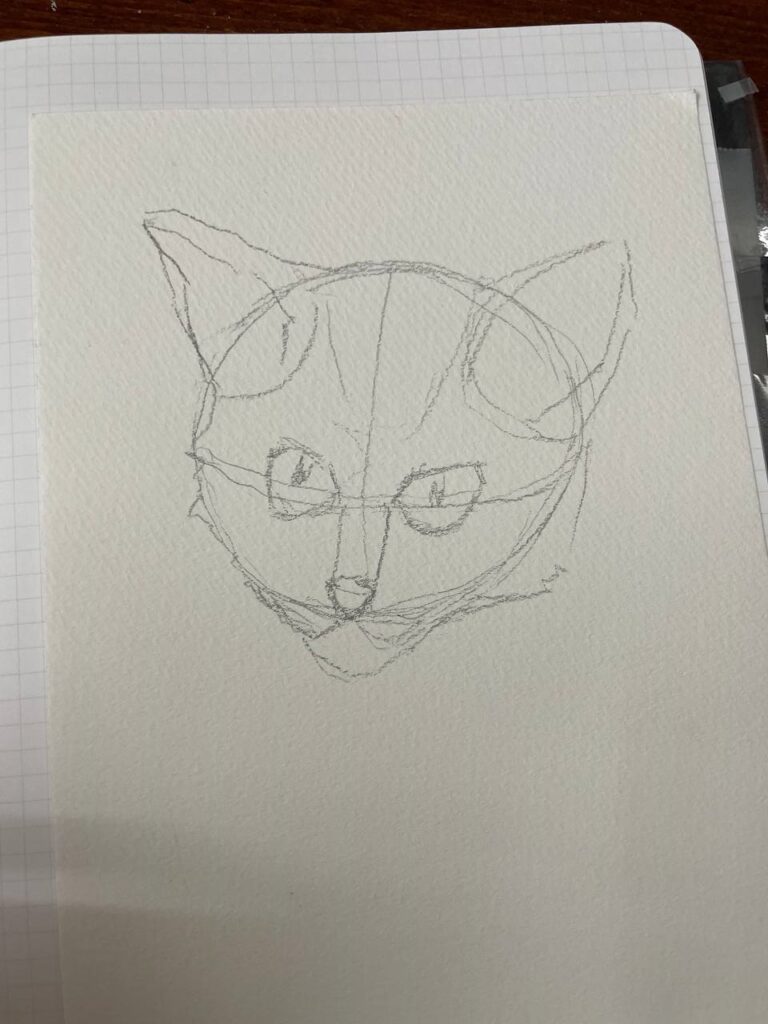

Instead, I’ll share some basic step-by-step guides on drawing cat faces from three different angles: straight-on; side profile; and ¾ view. (I’ve drawn this from memory from a book I read ages ago, and I can’t remember which one it is.)

Straight-on:

Side profile:

3/4 view:

The drawings at the side of the pictures show that you can adjust the angle of the face. When the head turns one way, all of the features move along in that direction as well!

Examples

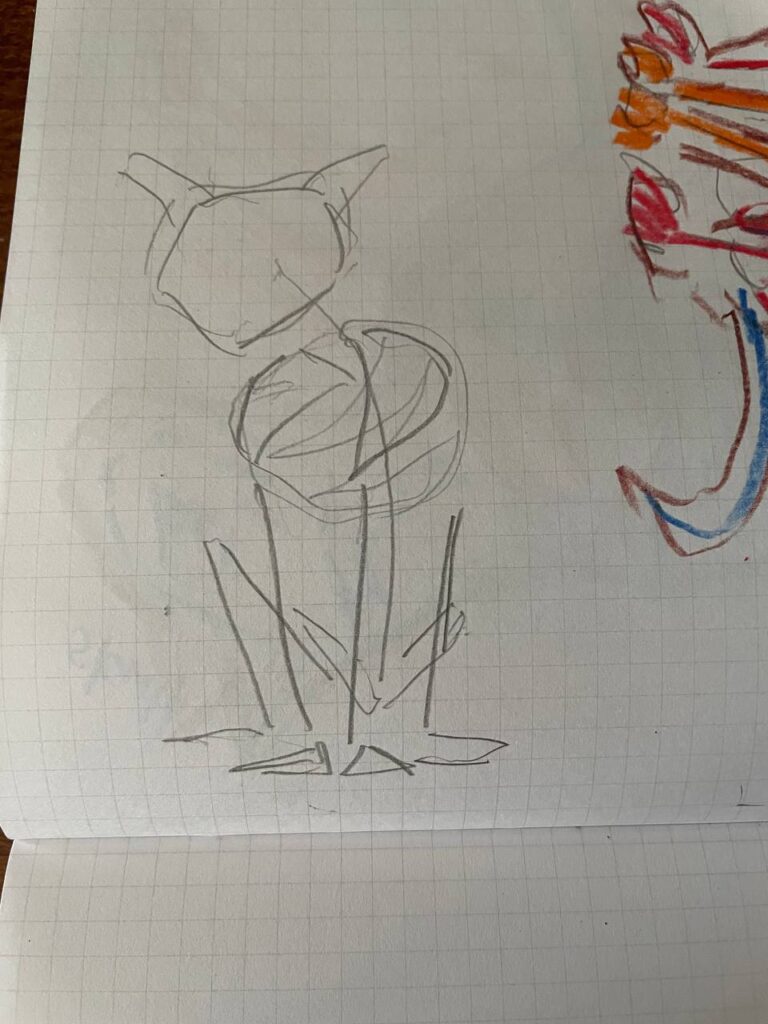

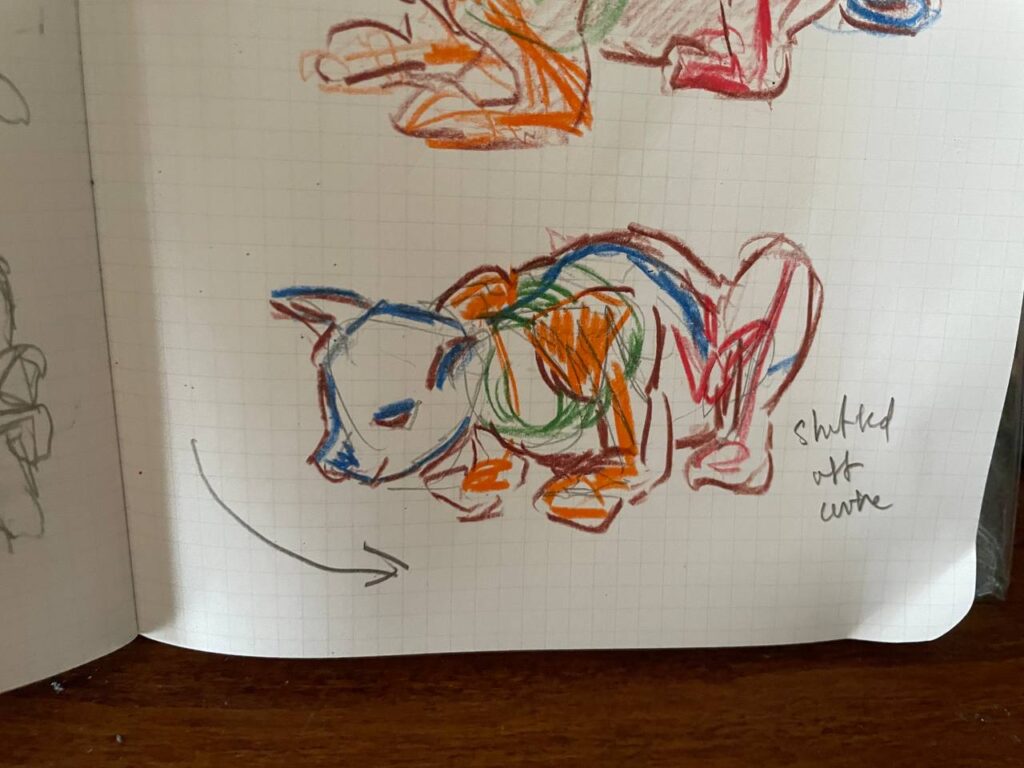

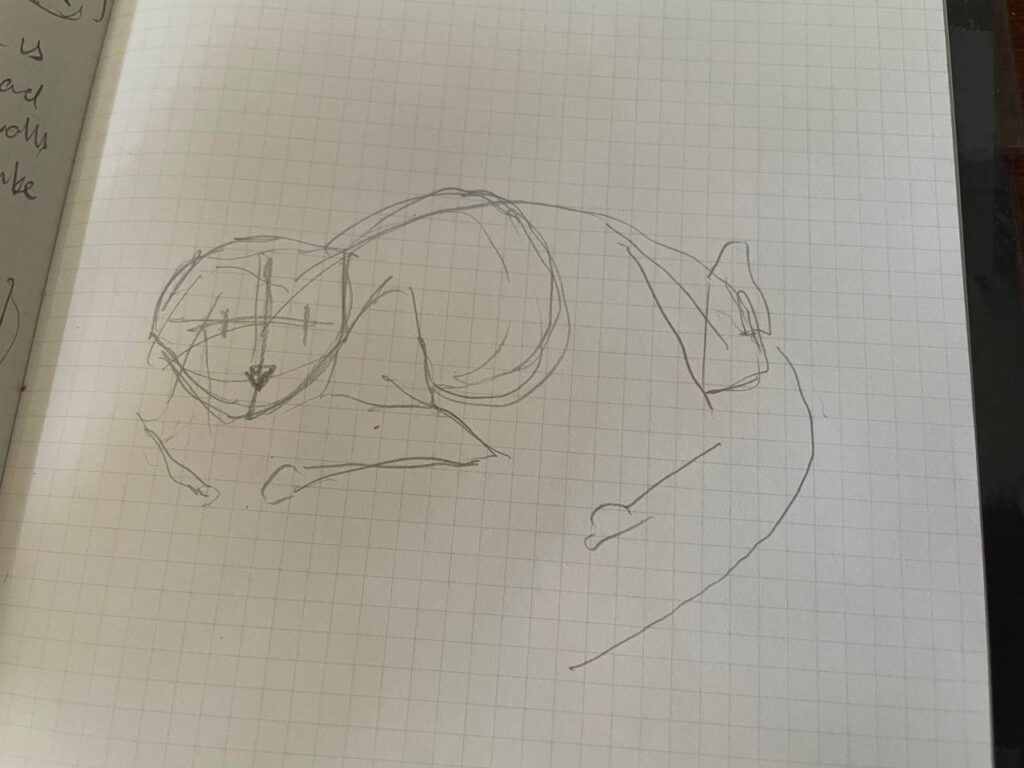

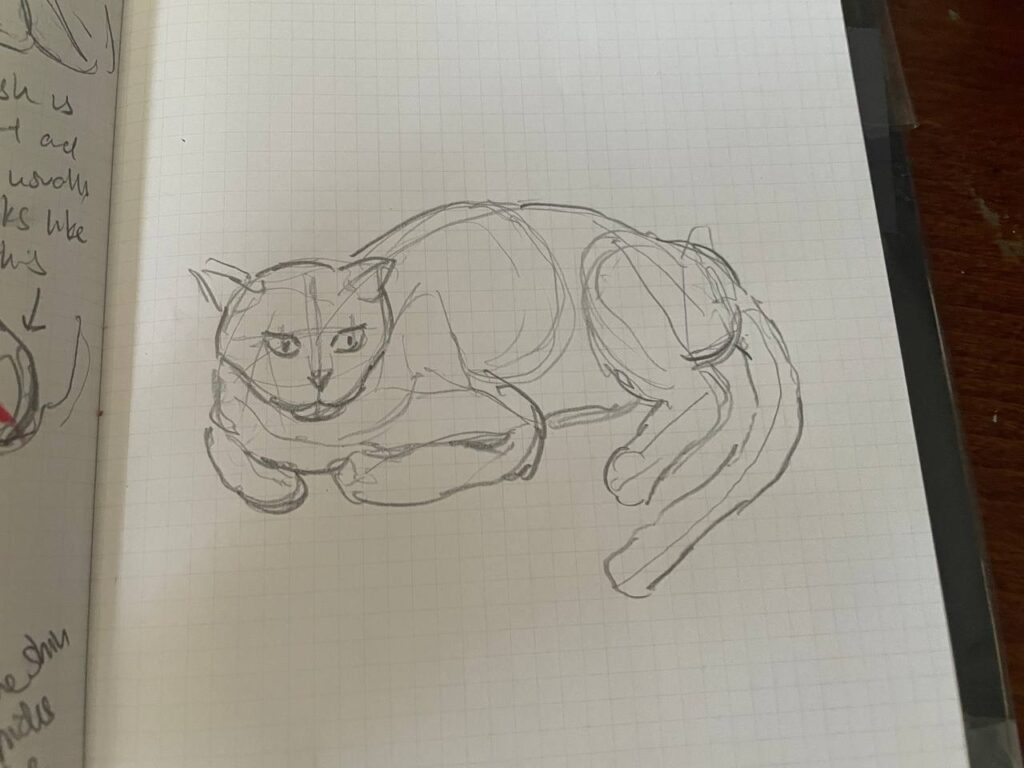

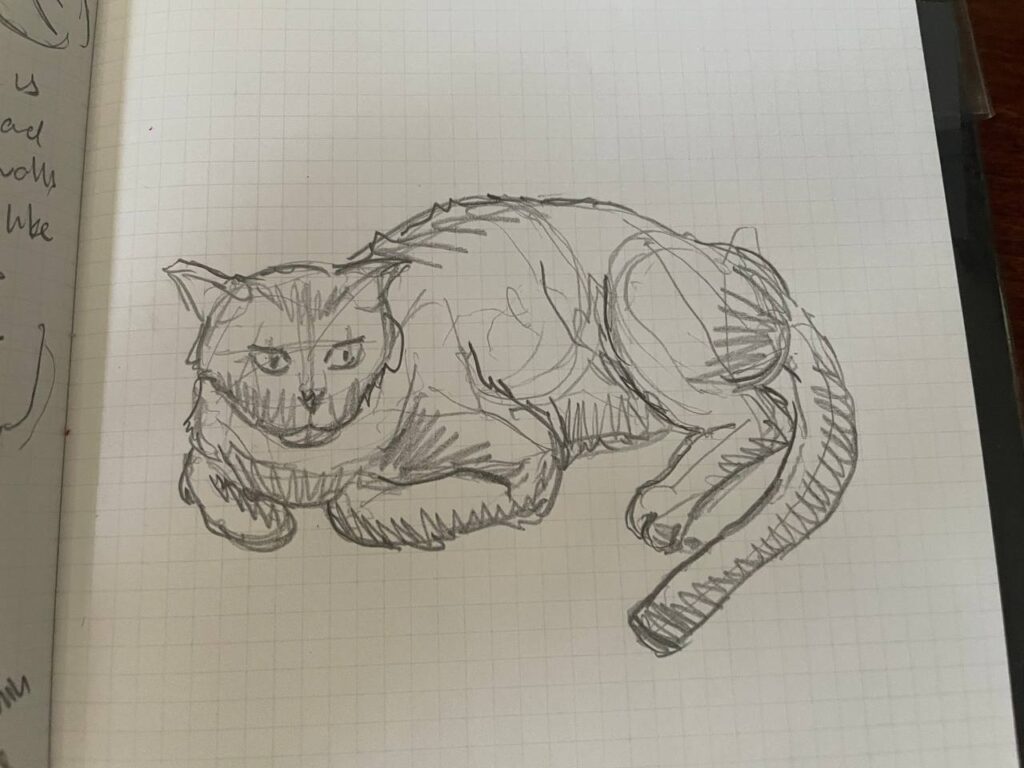

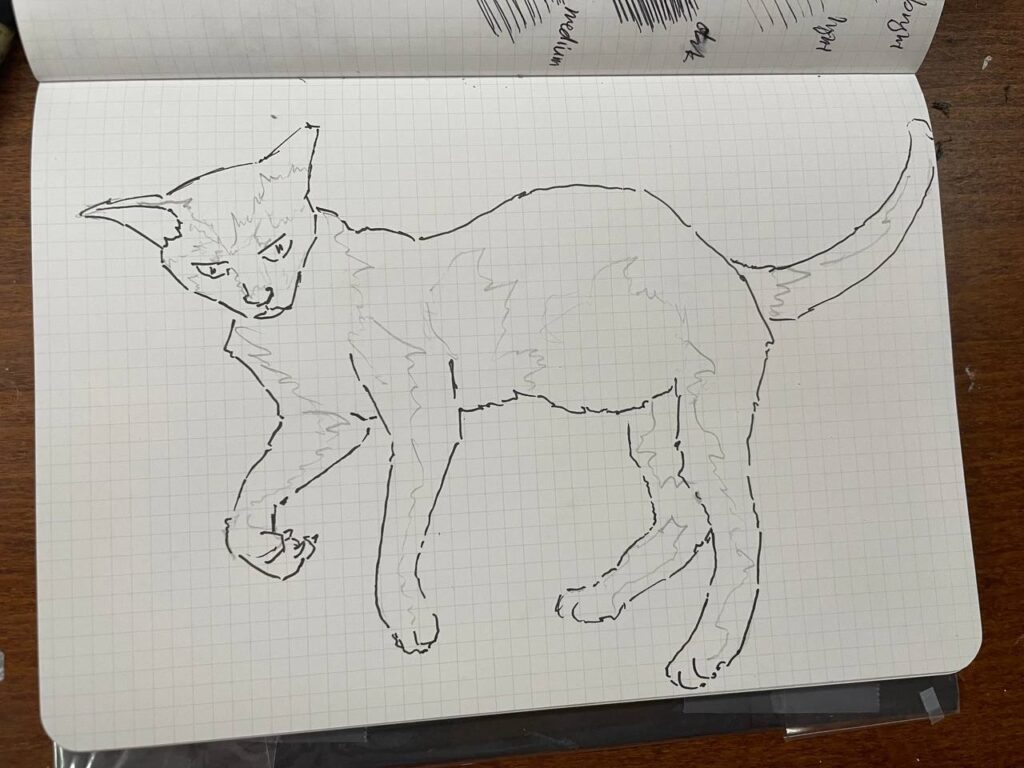

Let’s try drawing cats in various poses. In my opinion, it’s easier to start by finding the center-line by drawing the spine, and then sectioning off the large bone structures and limbs, before we add the meat. After that, we clean up the guidelines and draw in the details.

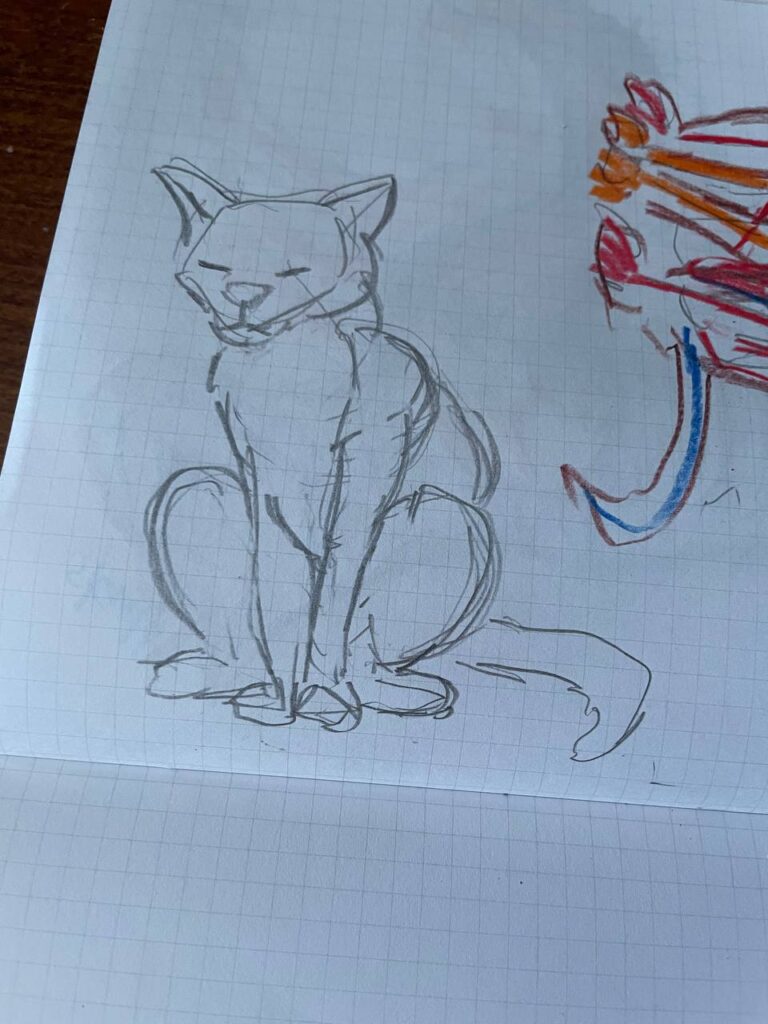

Here’s a cat squatting like a brooding superhero from the early 2000s:

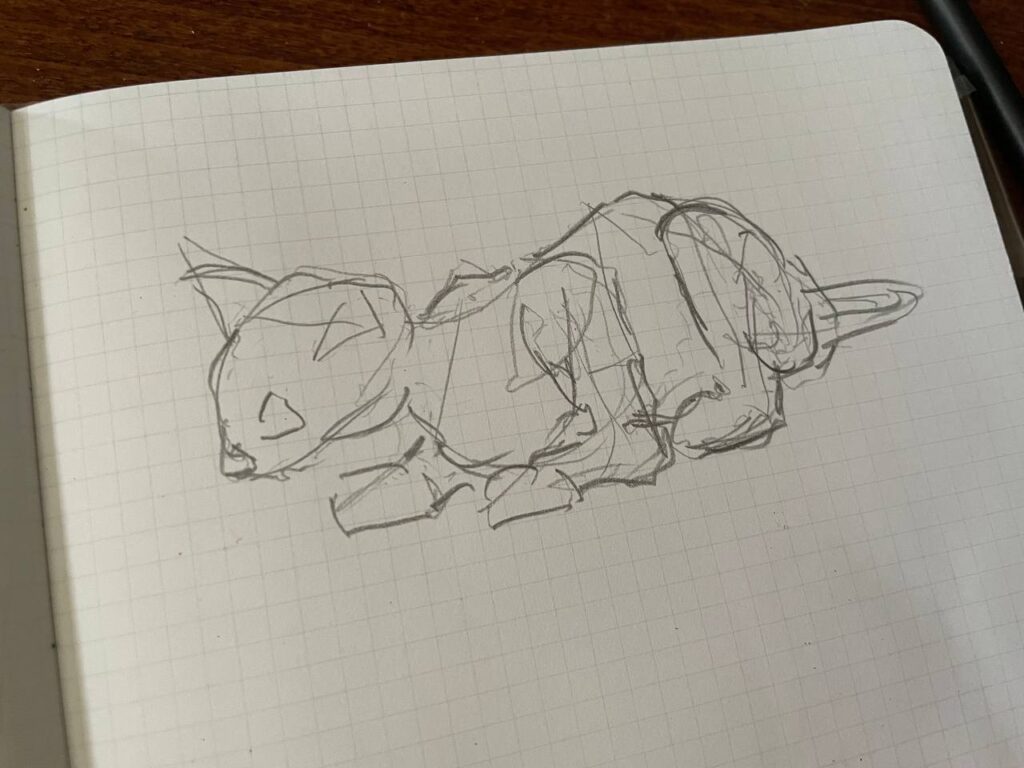

Here’s a cat waiting to pounce on an unsuspecting bird:

It’s a hassle to always draw in the skeleton – especially for the hind legs. Luckily, you can usually get away without doing that when the leg is in certain postures which are quite predictable.

That’s enough for now. I’ll probably show a few more examples of how to join the body parts into a figure, but integrate them into the illustrations for other points.

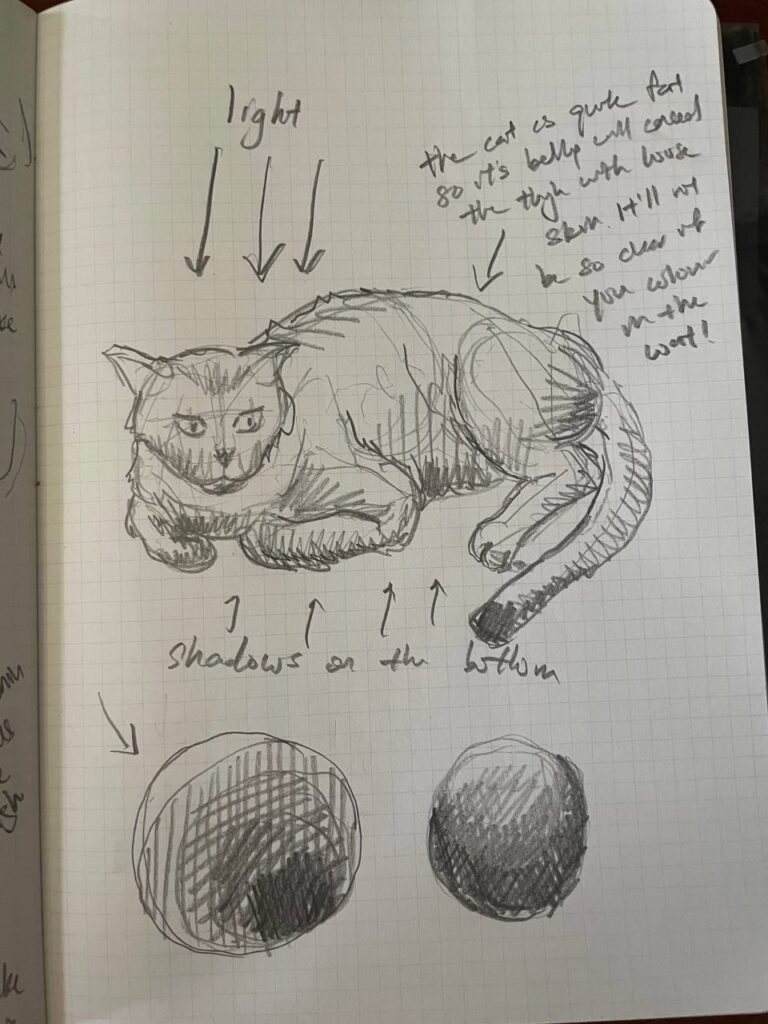

Lighting

Before we move on to creating “effects”, we’ll have a quick word about lighting. Lighting is important for transforming that flat 2D figure into a seemingly-3D form by making the drawing have more tangible weight. Basically, you decide on where the light is coming from in the drawing and then the shadows appear on everything facing away. The last image in the following set shows how the shadows might appear on a cat lying down.

I’ll not explain how to actually shade because (1) you could spend years learning how to do it properly and (2) I don’t actually know how. Basically, if you’re using a pencil, you can (a) press harder, (b) go over the paper more times, (c) make overlapping lines or (d) all of the above. If you’re using paint, you have to either make the paint thicker (use less water, for example) or darker (add a bit of blue/brown). If you’re using a pen, just go over the paper more times or make more overlapping patterns – pressing harder won’t do anything because the ink is the same and you’ll just tear the paper.

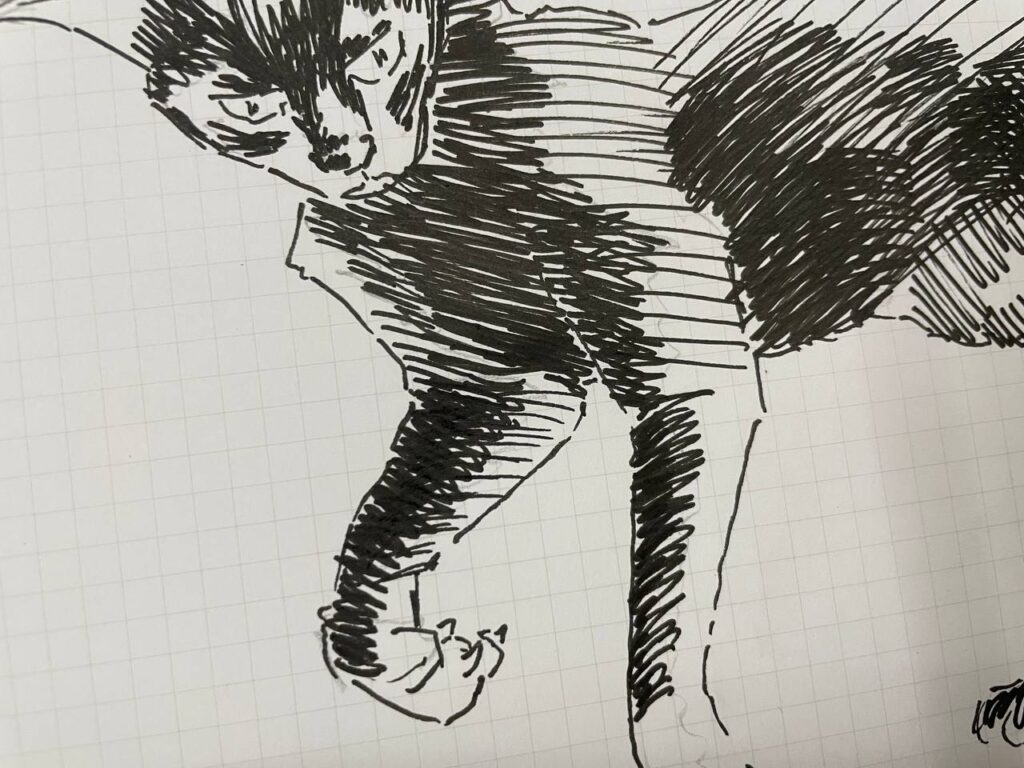

Personally, I like just scratching the paper and going zig-zag over the bit I’m shading. The way I did it for the tail, butt and belly look really good when you do it with a fountain pen because it looks rough and sophisticated.

“Effects”

This part is pretty fun. We’ve figured out what a cat should look like, but we haven’t worked out how to make our drawing look like the cats in school. Unless you’ve got a very good eye for cat-faces, you’ll probably have to distinguish them by their coats. Let’s see how we can use our drawing implements to create the effects to show their coats.

(I’m aware that there are many different cats in school but I’ll focus on the black cat and the stripey cat since those contain all the techniques you’ll need. I don’t like drawing the cat with the dirty-looking coat but you can do so by combining the techniques for the black and stripey cat.)

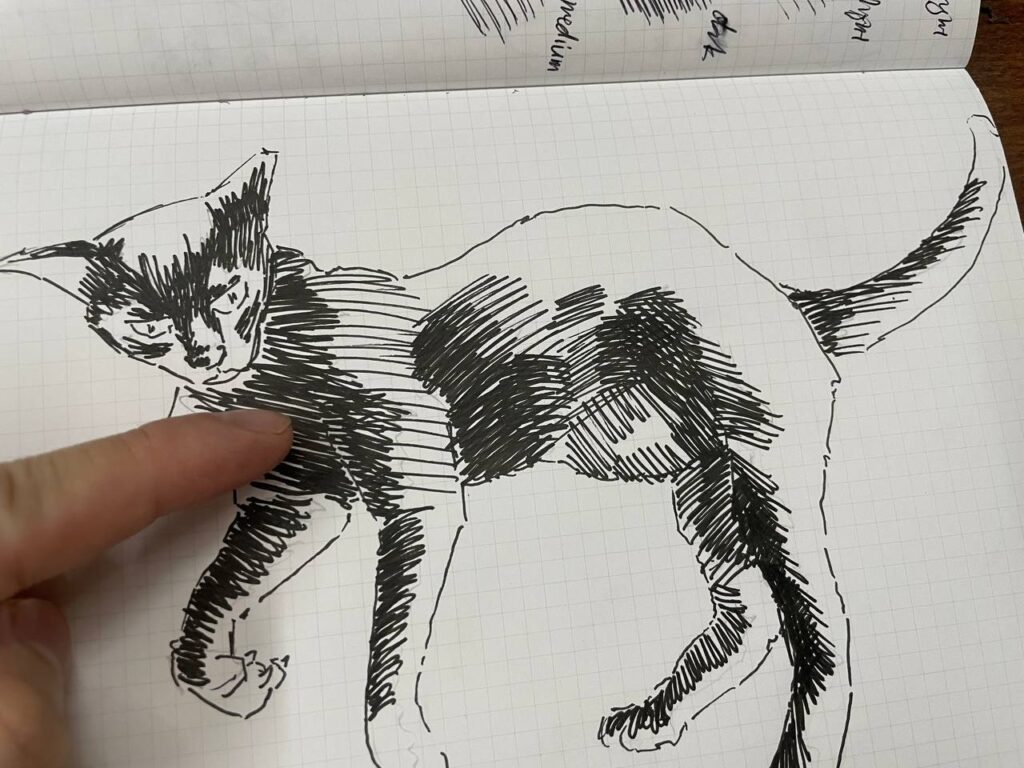

a) Black coat (pen sketch)

After you draw in the figure like normal, mark out the areas that should be especially dark. The usual lighting principles apply. Use your pen to hatch in the shadows with lines. I did them with straight lines and I tried to follow the direction that I thought the fur would go in. As these are the darkest shadows, you should make the lines really close and thick – you could even fill in the area a solid black, if you liked.

After that, fill in the normal black coat with more hatching. You could follow the same direction as before, which I think looks nice. I drew some in the same direction and some in another direction, so you can see how it looks. (You could do both or either, depending on your preferences.) Remember not to fill in the lines too closely since this is meant to be lighter.

Fill in a third layer of shading with even sparser hatching, then leave blank areas for the highlights. If you make a mistake, you can use correction fluid or opaque white ink to make highlights.

This method works well with an inky pen like a fountain pen, e.g., if you were sketching in your notebook. If you want it to look more realistic, add more layers of hatching with more a finer gradation of intensity.

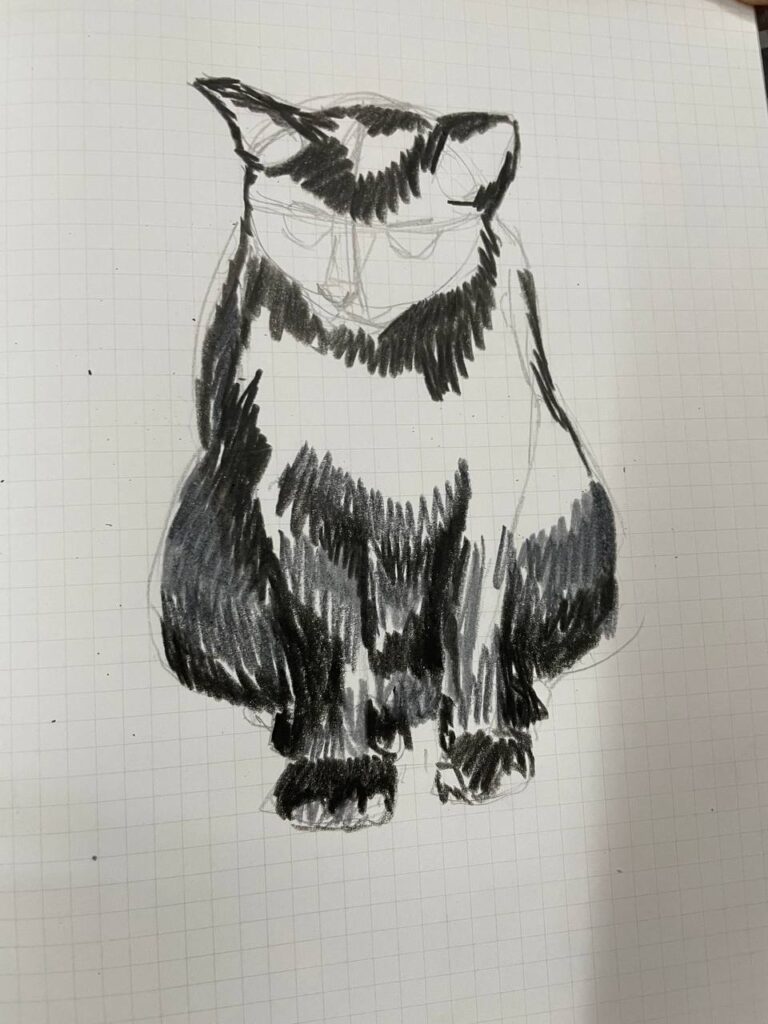

b) Black coat (color pencil)

Broadly speaking, you do largely the same thing as before i.e., use the black color pencil to fill in the darker shadows, then fill in the lighter shadows with the grey color pencil. When you’re using the greys, leave spaces for where the reflection lands.

I’m fairly sure you’re supposed to use color pencils after sharpening, so you can really get the details right. However, I think this way looks good and there are three tricks to making this work.

- First, leave some white spaces to create the impression that it’s supposed to represent hair.

- Second, use the color pencils blunt so that the wax smooshes when you mash it onto the paper and spreads out, so it looks clumpy.

- Third, try to follow the direction of the fur with your strokes to really make it look like you’re drawing clumps of fur that follow that direction.

The clumps, together with the small spaces, really emphasizes the direction so the body has more volume. I was inspired by this 9Gag video I saw years ago where a 3D artist was making a model for a V-tuber by drawing in wedges of hair onto the mannikin’s head. That’s a good mental prompt for this method.

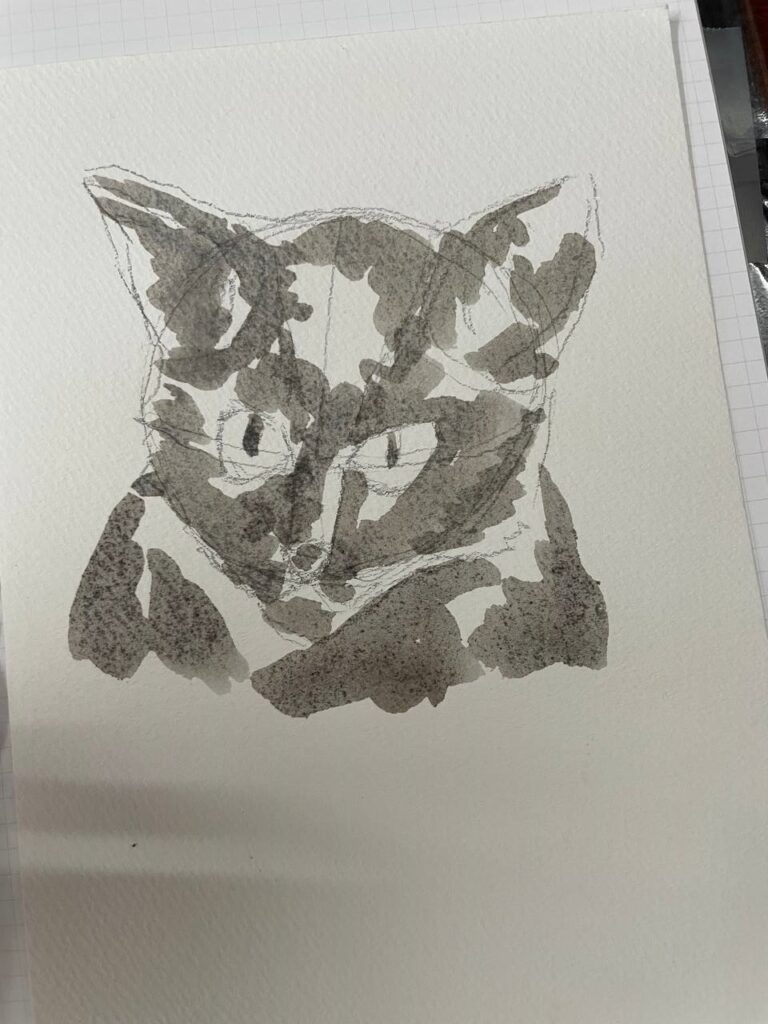

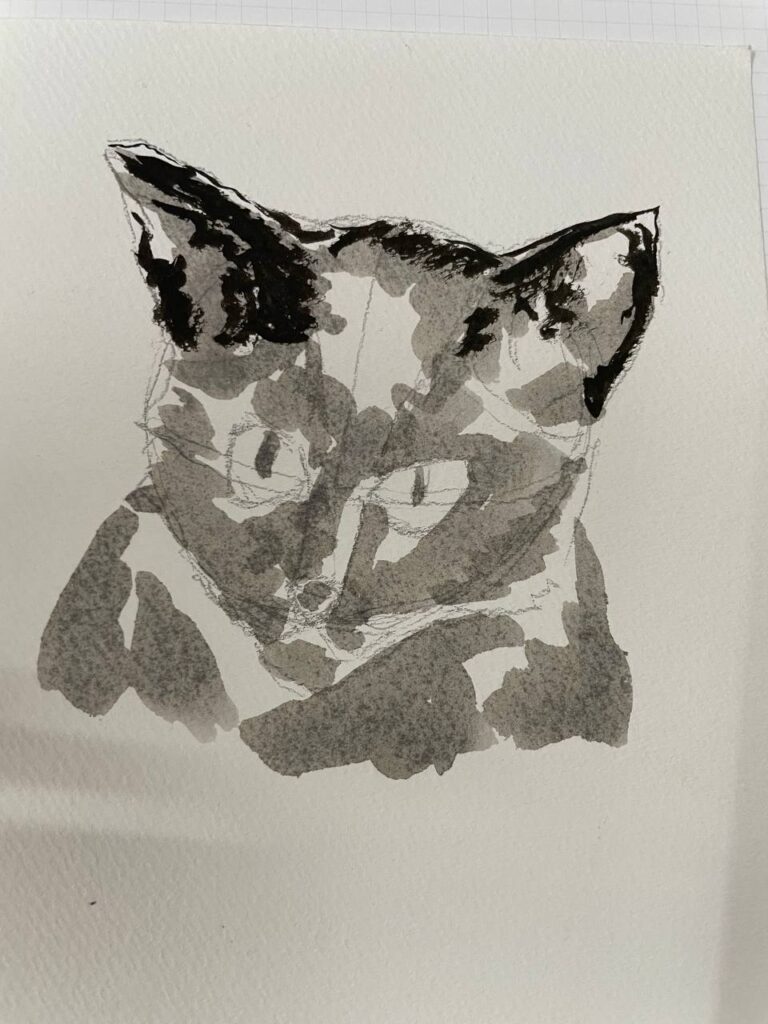

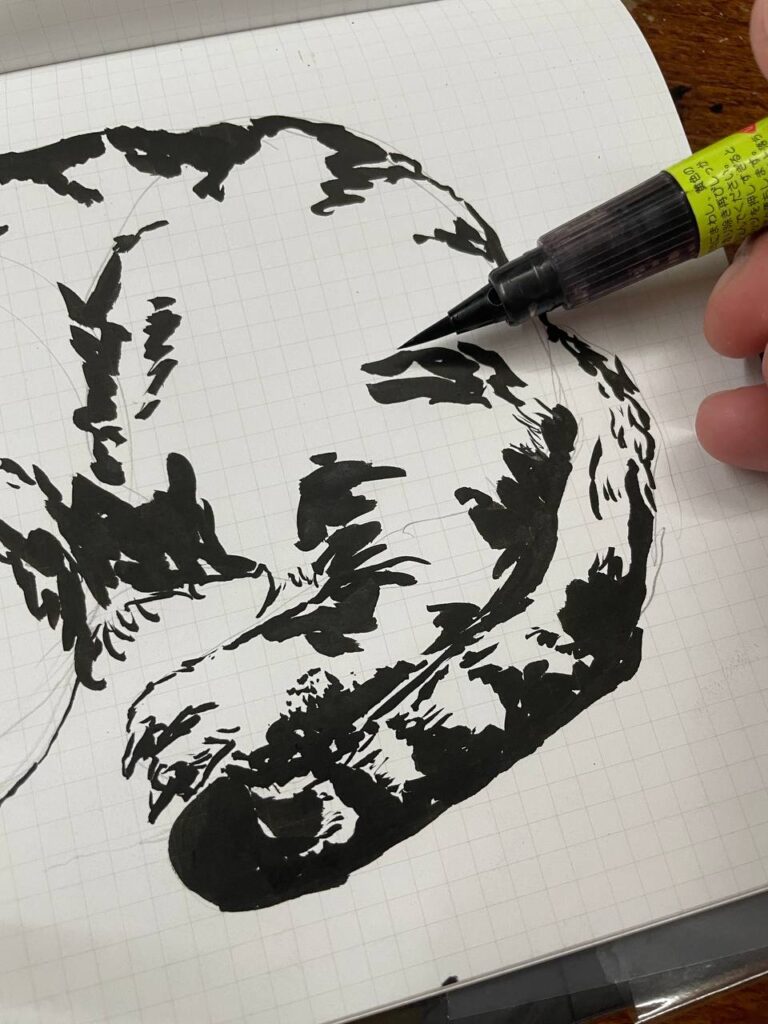

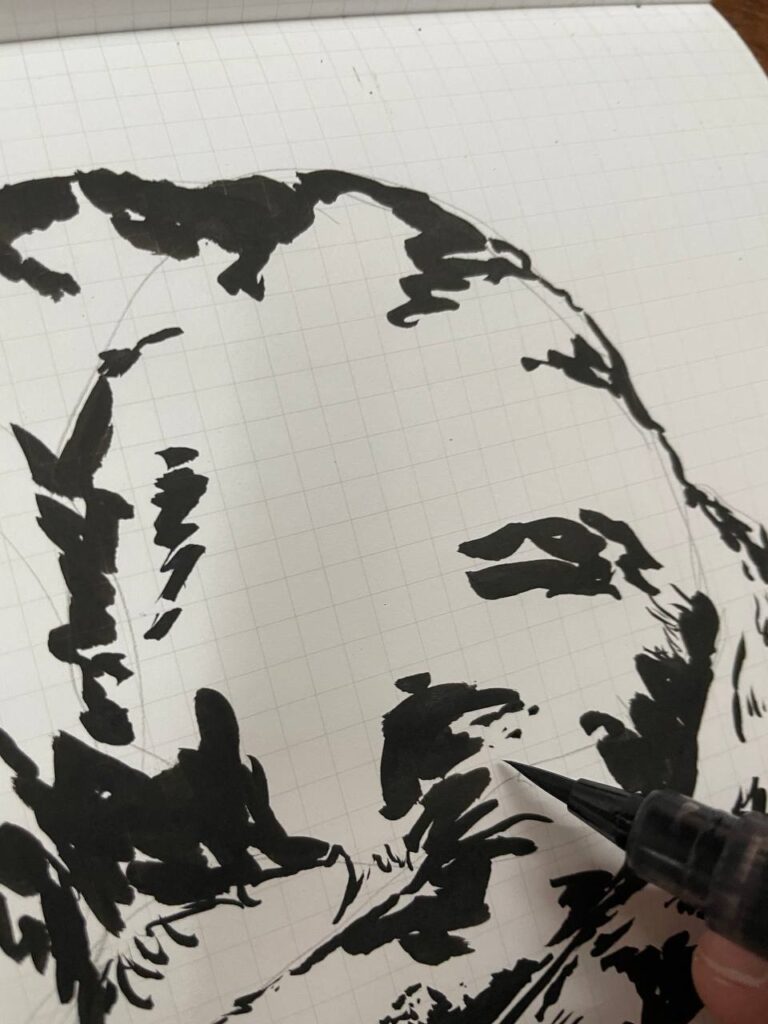

c) Black coat (ink and brush)

This is a pretty cool technique to use if you have two inks of different darkness. I made the grey by diluting some fountain pen black ink with water, and used that mixture to fill up a water brush pen, although you could also put that in a bottle and dip a brush normally. It’s a real hassle to get the intensity just right. My advice is to err on the side of caution by making it lighter rather than darker.

Anyway, with two inks (black and grey), you effectively have three tones: black, grey and white (where you don’t paint).

You start with the grey by filling in the areas that shouldn’t be white e.g., where there aren’t highlights due to reflections or bright spots. Don’t be upset if you paint too little or too much because you can always add more grey or open up highlights using a correction fluid pen or a bottle of opaque white ink.

Next, you fill in the shadows with the black ink. Hold the brush almost vertical and press very gently to create fine marks, which are good for tufts of fur or details. Hold the brush nearly flat to the paper to make thick marks, which are good for big shadows. Sometimes, it’s good to focus on one effect in an area e.g., the middle of the forehead is totally dark because it’ll help the eyes stand out. Other times, it’s good to have a mix e.g., at the lower part of the drawing where there are fine lines sticking out of the big black areas.

Another effect you can use is to dab your brush on a cloth to get most of the ink out, and then gently smear the long edge of the brush along the paper to get a feathery effect. This is great for fluffy bits, like the stuff inside a cat’s ears.

d) Stripey-coats (color pencil)

Unfortunately, I forgot to take photos of the work in progress so I’ll have to talk you through it.

The most important thing to do is selecting your colors. If you’re really good, you could pick out more colors for a more vibrant and realistic drawing. I’m not that good so I picked two main colors for the fur (a gold-like yellow and a slighter more orangey yellow), flesh pink for the nose and ear and a black and a brown for shading.

Unlike the black coat example, I made very small strokes that follow the direction very closely. The cat’s right ear is a good example. I’m very careful not to make too many strokes so I can leave spaces of white for highlights. Where I want to make a shadow, I try pressing harder and making closer strokes to remove any whites e.g., the right-most edge of the cat’s right ear and the front edge of its nose.

Let’s look at the cat’s forehead above his left eye. Observe how I make an arch with the yellow strokes where an eyebrow would be, since that’s how the orbital bone curves, and then I make sure to leave a blank spot at the corner of the forehead where the light would strike.

Let’s move opposite to its right cheek. Since the light is on the other side, this side is darker, which is why I made closer and more frequent strokes to leave less white spots. I also used a bit more brown to add a bit more shadow – don’t go too crazy though! Save that shading for his neck, which would be even darker. Use more brown and even a little black.

The last part I want to draw your attention to is his chest. This would be the darkest part of the picture, so there’s a lot more black here. However, keep it a small but intense shadow rather than spreading the shading throughout the chest even thought the whole chest would be under shadow. Too many black strokes might spoil the picture since it would look out of place amidst all the color.

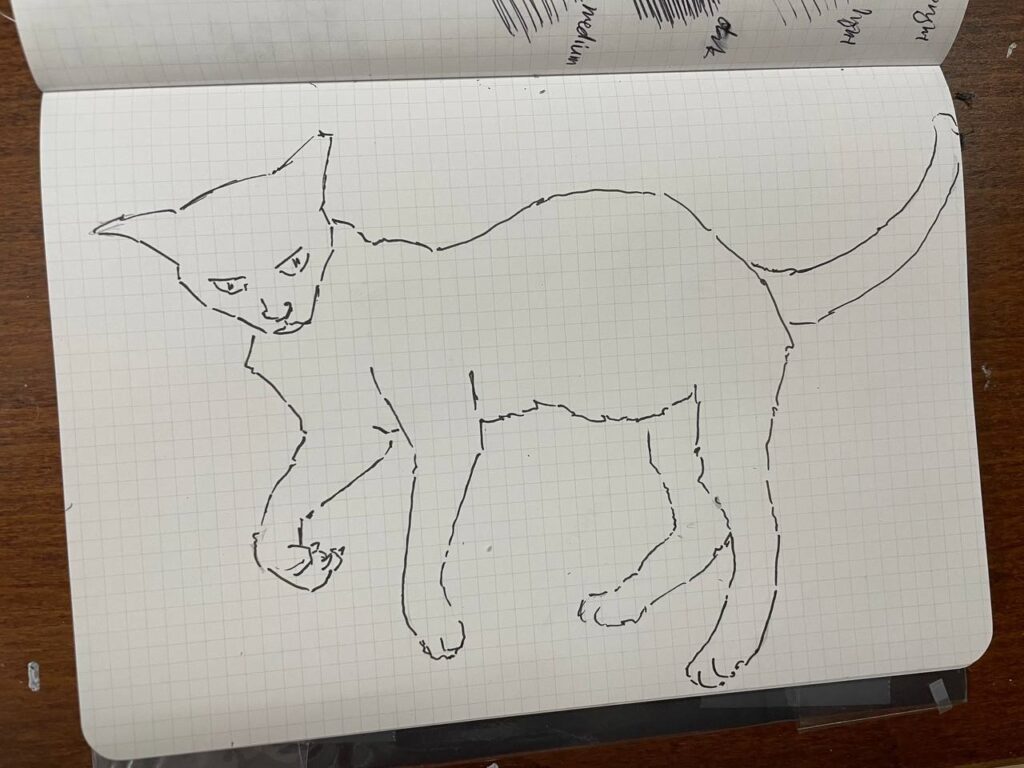

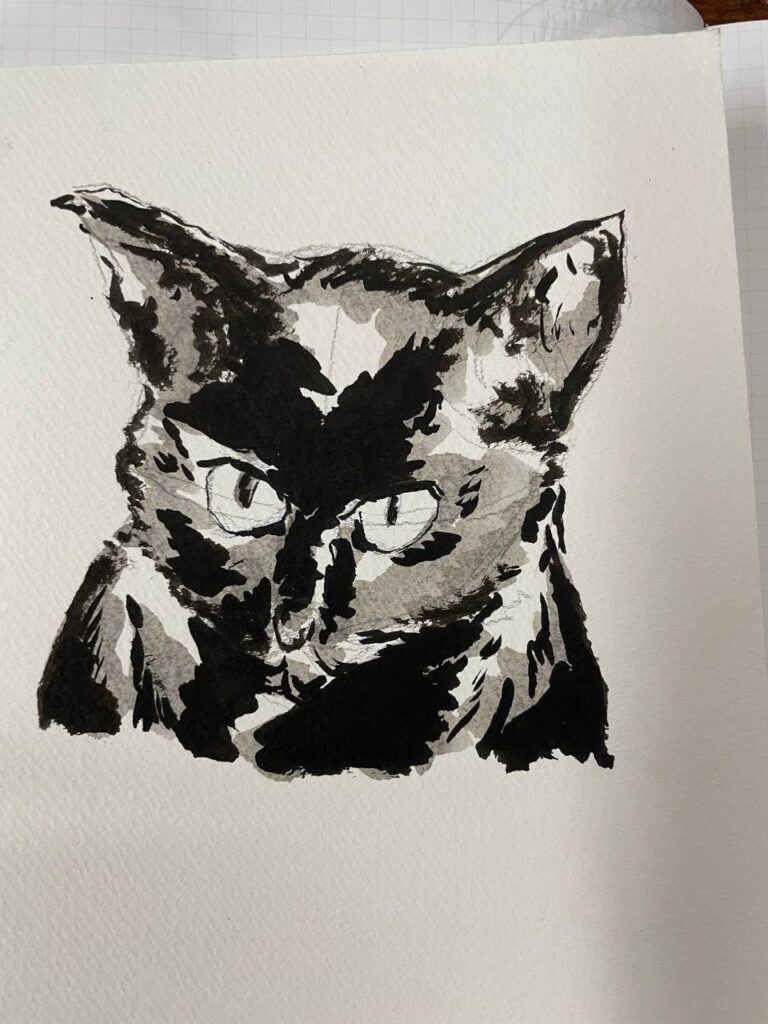

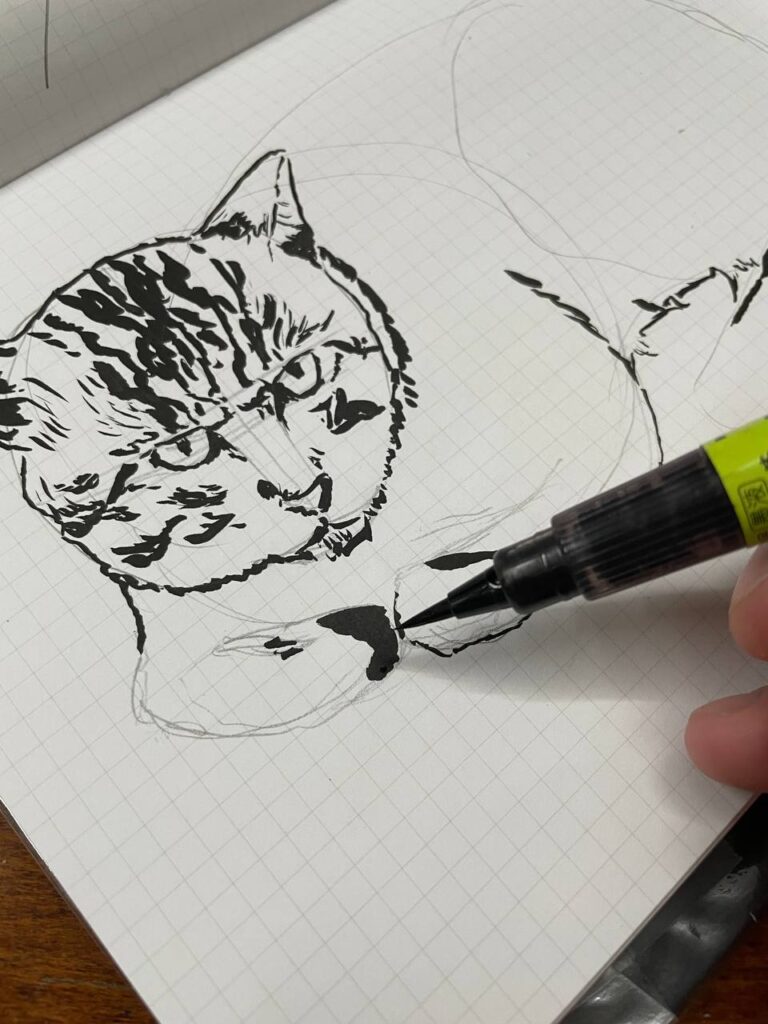

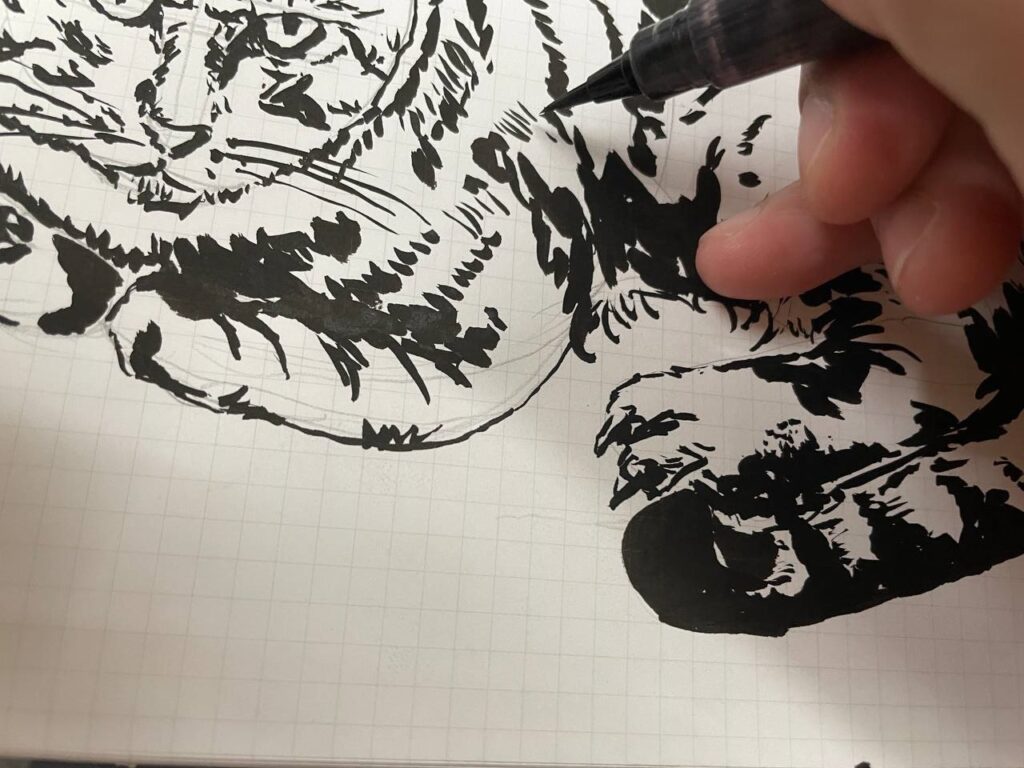

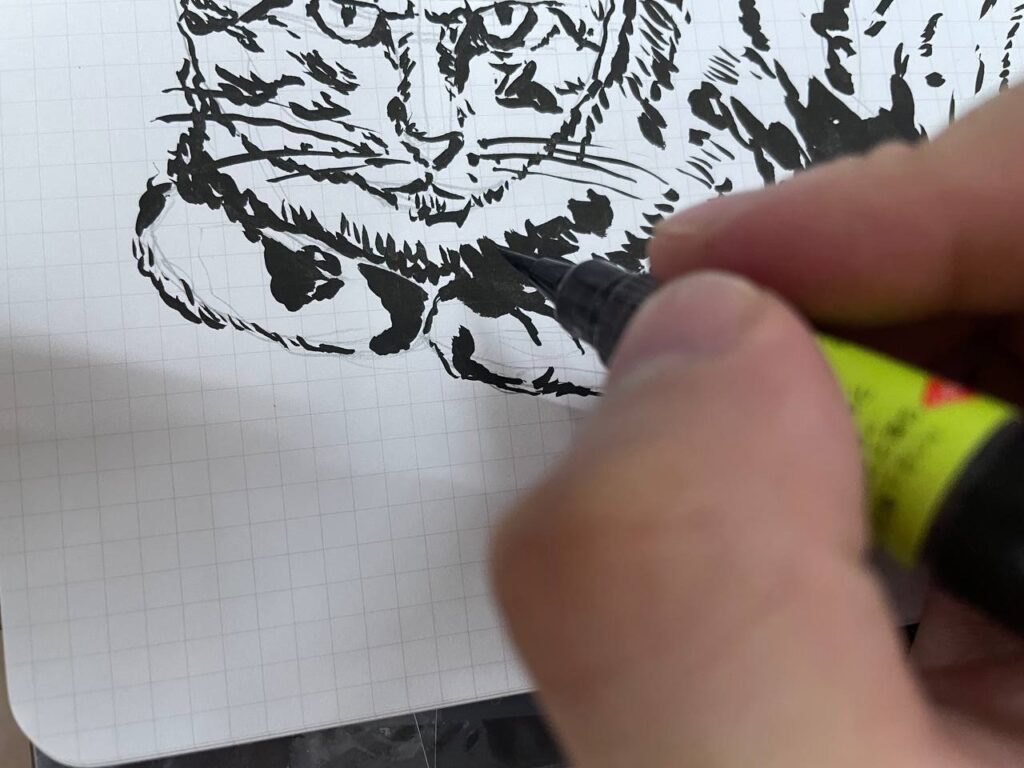

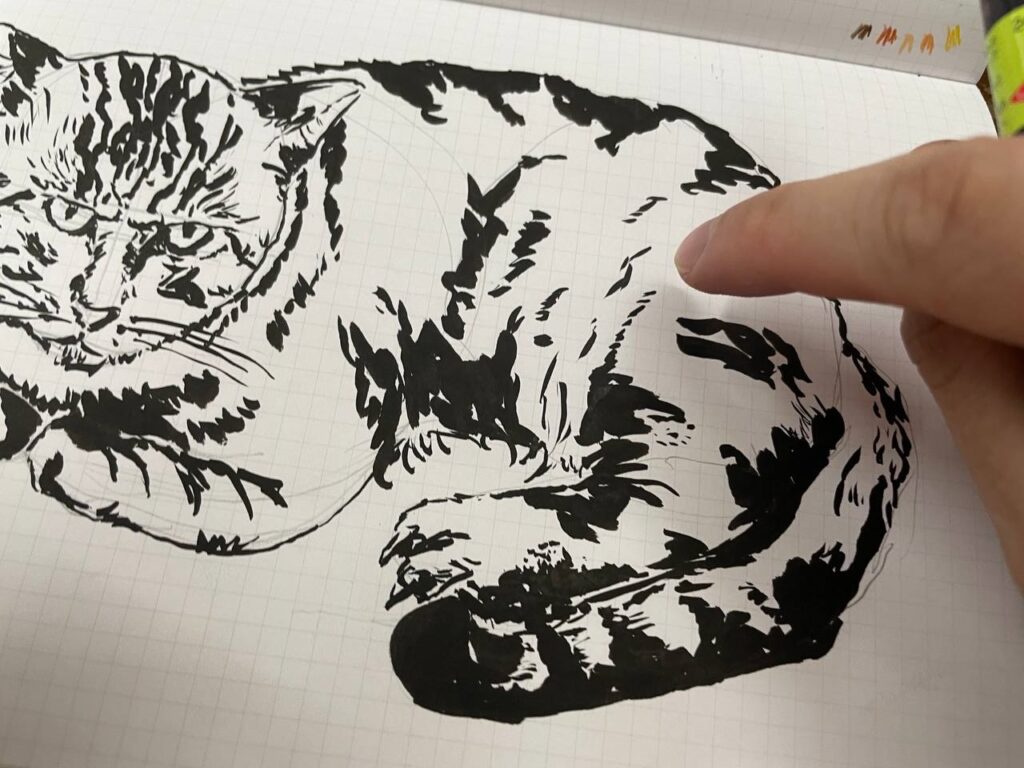

e) Stripey-coats (ink)

Here’s a very cross looking cat. Admittedly, it doesn’t actually look like the photograph I was referencing and his head stripes look funny but let’s try to look beyond that for now. (I had an accident and tried to even out the lines and then they got way too thick.) It’s too much trouble to explain the process so I’ll give you some pointers.

First, keep the brush vertical for fine details.

Second, use the flat edge of the brush for broad strokes to have deeper shadows.

Third, if you have a big area and you’re losing focus, don’t be scared to get lazy and fill in more space by using broader strokes. For example, if you tried to make the individual furs more apparent, this area here would be covered in many small strokes which would not only lack visual impact but also look like an army of marching ants.

Fourth, have a good mix of lines. With a brush, the monotony of having the same type of brush strokes gets extremely obvious very quickly. If you use broader strokes, add in some fine strokes. For example, I’ve added some small furs next to this bolder skin fold:

I did something similar here. If a skin fold interrupts a stripe in the cat’s coat, you can continue the stripe over the fold, which adds a bit more visual complexity.

Fifth, you can taper the shadows or add something to make that part look interesting. For example, if you have a bold line representing shadow (e.g., because that body part is going under the body), you can either taper the shadow with some small vertical strokes or add some detail to the furs there.

Sixth, in my opinion, empty space is your biggest enemy. When you’re doing a brush painting with lots of strokes, an empty space is incredibly conspicuous and you must hide it like a bald spot by adding lots of strokes there, even if they don’t make sense. With stripey cats, a good idea is to add some detail to the stripes in the coat. I like to tap the long edge of my brush onto the paper like this to create a solid-but-not-solid line, and you can do this for an entire stripe or just a little bit.

I was just demonstrating this with a brush because it’s fun, but you can do the same things with a marker or even a ballpoint pen. The idea is to just put the marks on the paper, even if you can’t vary the lines to the same extent that you can with a brush.

Conclusion

That’s all I know about drawing cats. I hope you found it fun and entertaining and I hope you’ll give it a try since it’s great fun. Bear in mind that a lot of what I said here isn’t the “correct” way of doing things. If you want to learn how to draw properly, you should probably focus on drawing shapes, learning perspective, proper shading techniques, values and master the use of pencils first. However, you don’t really have to do all that if you just want to have a bit of fun. Just give it a go with a pen and paper and focus on putting the lines on the paper and seeing how it goes. See you next time!