This article is reproduced from the Innocence Project (Singapore) Website. Get the latest news, articles and updates from them here.

In September 2013, a student team from the Innocence Project (Singapore) took on the case of Abdul, who had been sentenced to imprisonment and caning for unlawful consumption of drugs. The team’s efforts played an integral role in overturning Abdul’s conviction and subsequent discharge amounting to acquittal.

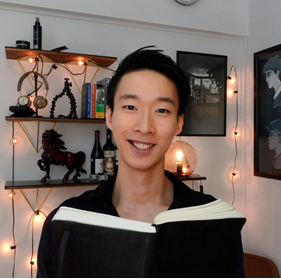

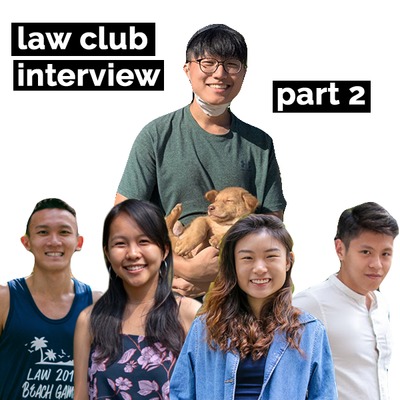

Every application that the Innocence Project (Singapore) receives is handled by one of our student teams, which conducts a comprehensive investigation including applicant interviews, on-the-ground investigation and legal research. Today, the Investigation team in charge of Abdul’s case, comprising Victor Leong, Ryan Nicholas Hong, Will Jude Vimal Raj and Allison Tan, shares their journey with Innocence Project (Singapore).

- Why did you join the Innocence Project (Singapore)?

As law students, there are very few things we can do which can create a tangible difference or to truly effect positive change beyond our books and research opportunities. This project provides an extremely useful avenue in helping accused individuals seek legal aid. Clichéd as it sounds, we were hoping to make a difference.

- What were your initial thoughts upon receiving your case?

At first glance, it seemed like the facts merited re-examination. For some of us, this was the first case that we undertook. We were therefore – naturally – excited and also slightly apprehensive.

- Could you tell us more about your interview with the applicant?

In this particular case, the applicant only spoke Malay. This was difficult for us, given that our previous experiences with interviews were in English. But it has to be appreciated that this is a very real problem for many accused persons who require assistance via IP.

In our case, a translator was necessary. This also presented problems which we didn’t expect. What we mean is, the meaning of certain words may be lost in translation, or that we might not be able to fully capture the applicant’s true expressions in light of our limited understanding of the Malay language. We also couldn’t stop him to clarify midway, because the answers were translated in blocks to us.

Fortunately, the problem wasn’t compounded as the applicant was willing to talk about his case, and he was certain about what he wanted to say. While he couldn’t furnish us with satisfactory answers at times, this was natural because it’s precisely why we need to follow up with investigations.

- How did you go about conducting research and collecting the requisite evidence for the case?

We divided the work into tracing the relevant parties on the one hand, and going through the court transcripts on the other hand. The research was not a problem given that we had many resources at hand — an advantage of being a student.

On tracing the relevant parties, we were very fortunate that the parties were readily identifiable — the lawyer, the hospital, the clinic. These were solid bases to start from. Unfortunately we didn’t have the contact information of one of the more “personal” witnesses — the accused’s girlfriend.

We obtained the court transcripts through CLAS.

- What were some of the challenges faced while working on this case, and how were they overcome?

The biggest challenge was definitely following up on the evidence, because there are limits to what we can do as students, especially contacting organizations such as hospitals and clinics.

Another problem is that it’s quite normal that the applicant couldn’t provide us with the contact details of certain key persons – or if the contacts were provided, they may be outdated. This is certainly not out of the ordinary, but again highlights the limits on what we can do as students.

- What were some takeaways from this case? What were your thoughts upon finding out that the applicant’s conviction was successfully overturned?

It is extremely encouraging that as law students, we have the opportunity and ability to change others’ lives for the better. The success of this case is certainly a testament that our efforts can lead to results.

Truth be told, given that IP in Singapore is very new, we were just doing our best and hoping to make a difference — that explains our reactions of utter shock when we found out the outcome. Now we truly know that it can be done. We are also really thankful for the lawyer who decided to take up this case, because it couldn’t have been done without him.

At the end of the day, what was truly meaningful to us was the fact that the outcome wasn’t monetary (which it tends to be for some other projects). Rather, the result had a direct impact on the applicant’s life in general, and this was truly eye-opening.

- Could you share other memorable experiences during your time in the Innocence Project (Singapore)?

Visiting the applicants in Changi prison made the project come alive and made it more than an ‘academic’ experience. Although you sometimes see the beneficiaries of other projects, it is very much different when you actually see them in prison. Furthermore, conducting the interview in a prison setting also reminded us of the urgency and importance of the project.

Following up on the cases on the members’ own accord is also definitely different from other projects. Therefore, it follows that IP is much more ‘open ended’ in this aspect. Furthermore, as our efforts have a direct impact on the applicant, this project certainly causes us to have a certain emotional attachment to every assigned case.

- Do you think that the Innocence Project (Singapore) has had an impact on your general outlook on Singapore’s criminal justice system?

In general, we feel not much has changed in the sense that there’s still continued faith in the system. Nevertheless, there’s much more awareness of the human element involved. This is especially so given the need to balance expediency with the practical impossibility of saying with certainty that someone is guilty.

At the same time, it is prudent to note that limitations of technology in one period may lead to changed outcomes in another. In the context of this project, developments that relate to DNA evidence – in particular – is significant, and we think an issue relating to this might come up in the future.

- Finally, what words of advice do you have for new members of the Innocence Project (Singapore)?

Please don’t pre-judge the case based on what you think. Always be meticulous in following up with every bit of available evidence and then make a reasoned conclusion.

Innocence Project members at a seminar on the 24th of February 2014.

This is the second part of a three-part article. The first part is available here, and the final part is available here. This post is also available on the Innocence Project (Singapore) Website